When rioters attacked the U.S. Capitol in a failed attempt to stop Congress from certifying the presidential election of Joe Biden, Washington Mayor Muriel Bowser lacked the authority to call in the D.C. National Guard to help police.

That episode has given new momentum to the District of Columbia’s long-running effort to become a U.S. state.

“I’m upset that 706,000 residents of the District of Columbia did not have a single vote in that Congress yesterday, despite the fact that our people were putting their lives on the line to protect our democracy,” Bowser said at a January 7 news conference.

Though Washington is the seat of U.S. political power, the district lacks local autonomy. Its budget and local laws, unlike those of states, are subject to approval by Congress. Its residents pay federal taxes but cannot send a representative to Congress to cast votes on their behalf.

“The United States is the only country that denies the residents of its capital city the same rights that everybody else has,” Eleanor Holmes Norton, the district’s nonvoting delegate to the U.S. House of Representatives, told VOA in an interview earlier this month.

Norton has championed statehood for three decades. In 1993, she filed a bill that, despite drawing the first congressional debate on the issue, was soundly defeated 277-153.

But she and some other district leaders and supporters who seek the sovereignty and autonomy of statehood contend they are closer than ever to getting it.

“We’ve never seen the groundswell of public support for statehood that we’re seeing now,” historian Chris Myers Asch, author of “Chocolate City: A History of Race and Democracy in the Nation’s Capital,” told The Washington Post Magazine for an article published in January.

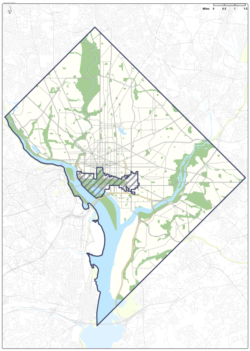

Norton introduced legislation, passed by the House last year, that would shrink the federal district to two square miles or 5.1 square kilometers, including the Capitol, White House and other major government buildings and monuments. The district’s remaining 66 square miles, or almost 171 square kilometers, would become the new state.

The legislation was reintroduced in January with more backers.

“What is important is that we have the support of the new president of the United States, Joe Biden, as well as the support of leaders of the Senate and of the House,” Holmes said. “That's a trifecta that's hard to beat.”

Republican resistance

The biggest barrier is Republican opposition in Congress and beyond.

Voters in the minority-majority district overwhelmingly support Democrats. Last November, 95% cast votes for Biden over the incumbent president, Donald Trump. Republicans do not want to see two more Democrats in a Senate now evenly divided at 50 seats each, with Vice President Kamala Harris, a Democrat, able to cast a tie-breaking vote.

In the House, Republican Congressman Dusty Johnson said he believes Washingtonians deserve representation — just not in a separate, new state. With his proposed legislation, most of the district would become part of the neighboring state of Maryland without adding seats in the House or Senate.

“If what D.C. residents really want is suffrage, if what they want is a voice in the United States Senate, my plan gives them that,” Johnson said.

“In the last 200 years, every single state that has been made a state has had either 6 million residents or has been 10,000 square miles” or nearly 26,000 square kilometers in size, he added. “... Washington, D.C., fails both of those tests.”

Johnson represents South Dakota, a Midwestern state with just under 900,000 residents in its nearly 200,000 square kilometers.

Joining another state is just not acceptable to Washington pharmacist Adeoye “Oye” Owolewa.

“We don't want to be residents of Maryland. We want to be D.C. residents,” he said. “We also want to have our own voice. We want to be the 51st state, not to be absorbed in another one.”

D.C. voters elected Owolewa last fall as a back-up delegate in the House of Representatives. He was born in the U.S. to parents from Nigeria, where residents of the federal capital region do have legislative representatives with voting rights.

Seeking broad support

Like Owolewa, attorney Paul Strauss sits on the New Columbia Statehood Commission. He has served as one of the District’s two elected “shadow” senators — again, without voting rights — since 1997.

He wants “to educate both Americans and the world about the importance of D.C. statehood and making sure that the United States lives up to the ideals that it preaches around the world.”

Strauss and his commission colleagues, along with statehood advocacy groups such as 51 for 51, are campaigning for support throughout the United States. They also have sought international backing.

“There may be some remedies in international law that might compel the United States to grant suffrage,” Strauss said.

The U.N. Human Rights Council has raised concerns about the denial of D.C. voting rights. Strauss said statehood activists have sought other support abroad.

“We've even appealed to neighbors in the European Union to work with their allies here in the United States to help bring equality to all of the Americans that live here,” he added.

The House Committee on Oversight and Reform has scheduled a March 22 hearing on Norton’s bill. A companion bill was introduced in the Senate in January.

But unless the Senate agrees to change the filibuster -- a rule that requires at least 60 votes instead of a simple majority to overcome opposition to a contested bill -- the legislation is unlikely to advance.