Amid a protracted political stalemate over a Supreme Court vacancy, the Senate’s most senior Democrat and Republican disagreed sharply on the way forward and what is required under the U.S. Constitution.

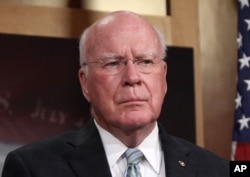

“We need to do our job,” said Patrick Leahy, the top Democrat on the Senate Judiciary Committee and the chamber’s longest-serving current member.

“The Senate does not play a rubber stamp,” said Orrin Hatch, the Senate’s most senior Republican and a Judiciary Committee member.

At issue is the nomination of Judge Merrick Garland, put forward by President Barack Obama to succeed Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia, who died in February.

Republicans say the seat should remain vacant until a new president is sworn in next year.

“Conducting a heated, divisive confirmation fight in the middle of an ugly presidential election – and that certainly describes our presidential election season that is well under way – would do more harm than good,” Hatch said Tuesday at a forum on Capitol Hill.

“Of course, we’ve had numerous, numerous Supreme Court nominees confirmed in an election year,” Leahy countered moments later.

The partisan tug-of-war over the Garland nomination has sparked fierce debate over precisely what is – and is not – required under the Constitution.

America’s founding document states that the president “shall nominate, and by and with the Advice and Consent of the Senate, shall appoint…Judges of the Supreme Court”.

“The Constitution gives the Senate the power of advice and consent, but does not specify how the Senate ought to exercise that power,” Hatch said. “Claims that the Constitution dictates when and how the confirmation process must occur – immediate committee hearings or timely floor votes – are false.”

“What would be historic is to deny Judge Garland a public hearing and a vote,” Leahy responded. “The Senate has considered controversial nominees. But in every one of those instances, the nominee received a public hearing and a vote,” Leahy added.

Republicans argue that the timing of Scalia’s death, when the 2016 presidential primary season had begun, makes this a special case.

“As a simple matter of precedent, the Senate has never confirmed a Supreme Court nominee to a vacancy occurring this late in a president’s tenure,” Hatch said.

Legal scholars at the forum also offered differing views.

“The Senate has a duty to consider a nominee, but how it exercises that duty is a matter of dispute,” said Martin Gold, who served as legal counsel to several former Republican senators. “In a sense, [Senate] inaction is also action.”

Jeffrey Blattner, who served as legal counsel to former Democratic senator Edward Kennedy, recalled a similar situation in 1988 when the Senate, then controlled by Democrats, confirmed Anthony Kennedy to the Supreme Court during Ronald Reagan’s last year as president.

“It did not occur to us [Democrats], ‘Well, it’s an election year. [1988 Democratic presidential nominee] Michael Dukakis could win, and we don’t have to go forward [with the nomination],” Blattner said.

No one at the forum disputed that Republicans have the power to hold a Supreme Court seat vacant for an extended period of time if they so choose. The Constitution sets no time limits for filling posts.

Even so, the question boils down to doing one’s duty and acting in the nation’s best interest, according to Democrat Leahy.

“We are elected to vote yes or no, not ‘maybe,’” Leahy said. “You should demand your senators do their job by providing this nominee a public hearing. We are called to fulfill our constitutional duties. We are called to lead.”

“The Constitution does not mandate a ‘one size fits all’ confirmation process, but leaves these judgment calls for the Senate to make,” Republican Hatch countered.

“The issue is when and how, not whether, the Senate should consider a nominee for the Scalia vacancy,” he added. “The Constitution leaves the judgment to us.”

A recent survey found less than half of Americans understand the Senate’s role in confirming presidential nominees. Even so, public opinion polls have consistently shown that clear majorities believe Merrick Garland, a federal appellate court judge, should at least be considered for the high court.