New worries about the state of the U.S.-South Korean alliance are emerging after the swearing-in of liberal Moon Jae-in, whose conciliatory position toward North Korea is markedly different from that of the Trump administration, say analysts who foresee increasing friction between the friendly powers.

In Tuesday’s snap election to choose a successor to South Korea’s recently ousted President Park Geun-hye, Democratic Party of Korea candidate and former human rights lawyer Moon won by nearly 20 percentage points, capping a decade of conservative rule in South Korea.

Frank Jannuzi, president of the Mansfield Foundation, a U.S.-Asia policy think tank, said the Washington-Seoul partnership that is at stake can be saved “only if it's carefully coordinated.”

“A U.S.-ROK [South Korea] alliance that integrates American pressure and South Korean engagement that includes an emphasis on denuclearization as an objective of [North Korean] policy, that could be a winning formula,” Jannuzi said. “But it requires careful alliance coordination.”

Demand for change

Moon’s ascent -- which many attribute to pent-up demand for change and the widespread anti-Park sentiment - signals a departure from Seoul’s current policy toward Pyongyang which cuts almost all ties to the reclusive regime. During the presidential campaign, Moon advocated a softer line on Pyongyang, calling for greater engagement with the North while maintaining pressure and sanctions to encourage change.

Moon’s approach invokes the so-called “sunshine policy” of South Korea during presidencies of Kim Dae-jung and Rho Moo-hyun. The “Comprehensive Engagement Policy towards North Korea” was announced in 1998.

It featured dialog and engagement with North Korea, including family reunions, but fell by the wayside with the 2008 election of Lee Myung-bak, a conservative businessman who had opposed the policy in his presidential campaign.

But as Moon, who was Rho’s chief of staff, takes a more conciliatory approach, he could face tension with the Trump administration. Its strategy, although not fully spelled out, involves ramping up pressure on Pyongyang and tightening sanctions with the help of China, the North Korean regime’s major ally and economic lifeline.

“[The Moon administration] wants to go back to the economic engagement approach and … it's hard to reconcile that with this idea that we're going to put huge pressure on North Korea through even more severe forms of economic sanctions and cutting off the flow of trade and capital,” David Sneider of Stanford University’s Walter H. Shorenstein Asia-Pacific Research Center told VOA.

Collisions foreseen

Sue Mi Terry, a former senior North Korea analyst with the CIA, believes that there’s a real risk that Trump and Moon will collide on a number of issues in relation to Pyongyang. The two sides will “not be on the same page” she said.

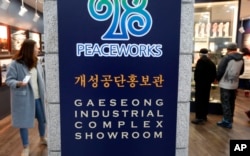

For example, Moon has indicated his interest in reopening the now shuttered Kaesong Industrial Complex, but Terry said Trump is likely to press his South Korean counterpart to keep it closed.

“Going forward, there will be a need for careful and thoughtful management of the alliance relationship by both Washington and Seoul,” Terry said.

The Kaesong Industrial Complex in the North Korean border city of Kaesong, a joint North-South project which was established in 2004 for substantive economic engagement and better ties between the two Koreas, has been closed since an early 2016 decision by Seoul to punish Pyongyang for its fourth nuclear test and a long-range missile launch.

THAAD as potential strain

In a discussion hosted by the Brookings Institution Tuesday, Jonathan Pollack, a senior fellow there, stressed that the U.S. deployment of the Terminal High Altitude Area Defense (THAAD) missile system in South Korea could also create a possibility of cleavage between Washington and Seoul.

While THAAD is intended to provide security against the growing North Korean missile threat to American troops stationed in South Korea, and the people there, Moon has expressed his discontent with the accelerated installation of the missile shield. He saw the early set-up as a move to prevent a new South Korean leadership from overturning the THAAD deployment decision.

David Straub, a former U.S. State Department official and a North Korea expert at the Sejong Institute near Seoul, said during the same online discussion at Brookings that THAAD is a critical issue to the South Koreans due in part to China’s ongoing economic retribution.

"There has been a great deal of economic suffering,” Straub explained. “The Chinese are quite blatantly punishing South Korea for not stopping the American deployment of a THAAD unit to protect American forces so they can better defend South Korea and deter the North Koreans.”

In his inauguration speech Wednesday, Moon vowed to have "serious negotiations" with the U.S. and China over the deployment of the anti-missile system. Pollack said, “This could inject a severe strain in the U.S.-South Korea relationship.”

Jenny Lee contributed to this report.