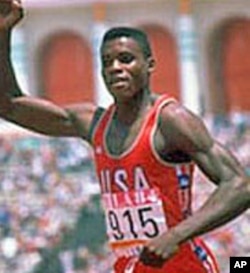

Carl Lewis dominated the sport of track and field for nearly two decades, earning nine Olympic gold medals in the 1980s and 90s. The athlete still holds the record for the indoor long jump, a quarter century after setting it.

These days, he is leaping into new arenas as an advocate for fitness, wellness and ending world hunger, including last month's launch of the UN's "1 Billion Hungry" project.

Fighting world hunger

To signal the start of the symbolic race to feed the one billion people living in chronic hunger, Lewis joined other celebrities and FAO employees at the agency's headquarters in Rome, Italy. They leaned out the windows and blew bright yellow whistles as a crowd cheered below.

Lewis leapt at the chance when the FAO asked him to help to raise awareness of world hunger.

"Fortunately, after 30 years of being in the public eye, I have a global voice," he say. "And the idea is that I'm shifting more work into public service and you know, that's my life goal. So, to me, it's just doing the work that I feel it's time for me to do."

Lewis gives time locally, serving as a volunteer track coach at his old high school in New Jersey.

Nationally, the Carl Lewis Foundation sponsors athletic programs for inner-city children and other causes. In October, Lewis went global with his charity work, accepting a position as Goodwill Ambassador for the U.N.'s Food and Agriculture Organization.

When the five-time Olympian accepted a medal from FAO Director General Jacques Diouf, he quipped, "This is best silver medal that I've ever received."

The former track star remains fit and trim but has exchanged his trademark flamboyant Lycra track gear for an elegant black suit. On his first day at this job, he's more of a scout than an athlete, pledging to dedicate himself to the FAO's mission of making sure all people have access to food.

"And I'd also like to reach out to all of my athletic friends and family," he tells the audience, "and I hope that they understand that their legacy is the relevance that they bring beyond and after their athletic careers end. So thank you very much, and thank you for having me. And let's go to work."

Setting goals

Lewis is well-trained at setting and achieving goals. It's in his blood.

His mother was an Olympic hurdler and his parents managed a local track club. Lewis captured the national high school long jump record in 1979 before heading to the University of Houston. The next year he made his first Olympic team. For seven years, he didn't lose a long jump competition.

"I don't think that he was the best talent we had," says Joe Douglas of the Santa Monica Track Club, who managed Lewis' golden career. "I just think that his talent overall which included his focus...he said that I am going to do it. He would do anything that it took to be a great athlete. And that's hard to find anymore."

Lewis also pushed for professionalizing the sport. He called for changes that permitted him and subsequent generations of athletes to earn a living and extend their careers long beyond college.

However, his activism angered many. Lewis' track career also closed under a cloud of controversy. He lobbied to be put on a relay team at the 1996 Atlanta Games even though he hadn't trained with the squad. The U.S. coaches refused.

A life after sports

After retiring from sports in 1997, the superhuman Lewis became all too human.

An aspiring actor, his work was largely panned. In 2003, he crashed his sports car while driving intoxicated. Drunk driving charges were dismissed after he agreed to attend alcohol awareness meetings. The crash made him re-evaluate his life and set goals for this second phase.

Lewis has won over U.S. track and field's CEO Douglas Logan, who says, "There are very few people in this world that are blessed with both talent and charisma. And Carl has both in incredible doses."

Logan met Lewis shortly before the 2008 Beijing Olympics. At the Games, the U.S. track team had a raft of problems including dropping batons during relays. A desperate Logan sought out Lewis.

"It was a two-and-a-half-hour lunch and Carl did all the talking," says Logan. "His was the most insightful examination of where we were as a nation with regard to how we conducted our [sports] development. And laid out, almost in plan form, some very creative ideas with regard to how we could improve."

Logan put Lewis on a task force that has crafted a plan for the team as it prepares for the 2012 London Games. The track executive called Lewis a spiritual leader, a different view from his competitive days when he was labeled aloof and a spoilsport.

Logan said a track and field event in Pennsylvania summed up for him the real Carl Lewis.

"A youngster was looking for his autograph and didn't have anything to sign it on. And Carl - I mean, without even thinking about it - took a pen, autographed the shirt that he was wearing and literally gave this young person the shirt off his back."

Still running, for a cause

It may prove to be excellent training for future travels with the United Nations to some of the world's poorest countries. For those he's helping, he'll always be remembered as King Carl, who reigned in track and field.

And that's okay for Lewis who also holds dear many moments from the track, especially receiving his last Olympic gold medal.

"I knew I was leaving, that it was over and that was it," he explains. "But I tend to tell myself every morning when I get up that I haven't seen it yet. And I try to live that way. That is why I continue to try to do new things. And that's why it's so special.

The longtime vegan and fitness advocate plans to celebrate his 50th birthday next year by competing in a marathon.

In the meantime, he'll be running around the globe in the fight to end world hunger.