The miniature yellow truck whirls around on the concrete, polished shiny by its wide wheels. Wade Tate grabs the steering wheel with both hands, glances behind him and maneuvers the truck backward, then abruptly forward, as its oversized fork scoops up a heavy box.

He programs it to lift: up, up, up, to the second level of shelving, where he gently places the box between two other boxes of differing size.

For more than half of his life, Wade Tate couldn't even drive a car. That's because he was behind bars, serving a 25-year sentence after pleading guilty for two murders.

"Everything I learned in prison, the trades I took, helped me to hold down a job like I'm doing today," says Tate.

For three weeks after he was released, Tate applied for numerous jobs but never got called back. "My goal was to get a job,” but with a criminal record, he said, “it is hard to get one."

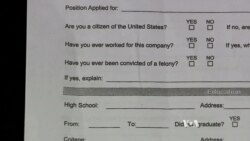

The application box

Many U.S. job seekers face application forms that ask whether they have ever been convicted of a crime and require them to check a “yes” or “no” box. Checking "yes" immediately excludes applicants from some jobs.

But an international movement by civil rights and prison reform organizations is urging employers to "ban the box."

Activists are pressuring municipal and state governments to reform the system. Just over 20 states now have some rules deleting the question from private or public applications. An applicant who passes that first round of winnowing still faces additional screening. Employers can ask the question in an interview and also conduct background checks.

A main proponent of “ban the box” legislation is Maurice Emsellem, program director of the National Employment Law Project.

"I think there is overwhelming support for rolling back all the damage that was done over the last couple of decades related to mass incarceration," says Emsellem. "The box has opened up a broader conversation about hiring commitments and policy reforms regarding former felons."

The Obama administration gave the effort a boost last November when it asked Congress to "ban the box" on federal hiring applications as part of a larger initiative on "rehabilitation and reintegration of the formerly incarcerated."

White House figures show 600,000 people are released annually from federal and state prisons. Getting their lives on track includes adjusting to family and neighborhood structures and supporting themselves financially.

Having the 'conversation'

But the “ban the box” movement has its critics.

The National Federation of Independent Business opposes a ban for several reasons.

Mozloom says his organization is against banning the box for several reasons. One is practicality. Because they operate small businesses, "our members don't have a human resources department. They are the HR department,” says communications director Jack Mozloom. “The owners advertise the jobs, pull the applications, schedule the interviews and conduct them. The ability to ask criminal records on an application saves time and money, which they don't have."

His members have nothing against giving prospective employees a second chance, Mozloom says. But, "ban the box prevents the conversation from happening in the first place."

The initial hiring application form for Kelly Generator & Equipment of Owings, Maryland, is in line with what "ban the box" advocates seek. It doesn’t include a question about a criminal background. But owner John Kelly doesn't want to see the rules encroach any further.

Kelly says it’s bad business practice to keep information from a potential employer. He says a high level of trust – among him, his employees and their co-workers – has contributed to his company's success.

"You know, I would hate to hire a comptroller or somebody for the comptroller position who had gone to jail for embezzlement,” he says. “For me to not know that before I hire him and then have him in a position [with] a fiduciary duty, I mean, that's just ludicrous for us not to be allowed to know that.”

Kelly says that individuals cannot erase their past and that the truth must come out before a hiring decision is made. And, to make a proper decision, managers need as much information as possible. He doesn’t want the government to limit the ability to hire the best people for each position.

Getting the chance

Forklift operator Tate finished 14 weeks of classes through HopeWorks, a faith-based nonprofit that matches ex-felons with employers who will not view their criminal record as a deterrent. HopeWorks found Tate his job with DSI Warehouse of metropolitan Memphis, Tennessee.

Ronnie Martin started the company and has hired several ex-convicts.

"I think felons have to prove to themselves that they can handle the job. If they prove it to themselves, then they will prove it to me," says Martin as he helps load a box onto a truck. "I'd hate for someone to check my past too closely."

Says ex-offender Tate, "If we don't ever get the chance, they [the employers] don't know how hard we will work."