WASHINGTON —

As the Islamic State of Iraq and the Levant (ISIL) continued along a bloody path toward Baghdad, President Barack Obama announced Thursday that the U.S. has stepped up “intelligence, surveillance and reconnaissance assets” in Iraq to get a clearer picture of what’s going on there.

With better information about what ISIL is doing and where, the U.S. can better support the Iraqi military in countering the threat of Sunni Islamist forces. That may be good news for the Iranian-backed Maliki government in Iraq, but is not expected to sit well with Sunnis outside of Iraq – in particular, Sunni monarchies of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other Gulf countries.

Assigning blame

“This is very much a situation of competing narratives,” said Salman Sheikh, director of the Brookings Doha Center and fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy.

“The Maliki government, the Assad government, as well as Iran, are seeing this very much as a fight between elected governments and Sunni extremists, al-Qaida extremists," he said.

“On the other side, you’ve got a narrative which is very much about the grievances that are being done to the Sunnis' heartland, particularly in Iraq by Maliki, and of course by a minority in Syria to the majority Sunni population,” Sheikh said.

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki has blamed Saudi Arabia for supporting the Sunni extremists with weapons and cash. But Saudi and the other Gulf countries throw the blame right back at the Iraqi leader, a Shi'ite, saying his own “sectarian and exclusionary policies” led to the current crisis.

They also criticize the United States for its ongoing support of Maliki, warning that if the U.S. continues to back him, it could ignite a regional sectarian war.

The situation is therefore enormously complex, Sheikh said, and one that places the United States in a political quandary.

Crisis was predictable

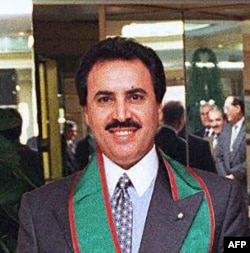

“Iraq is a mosaic of cultures, histories, ethnicities, religions and sects,” said Sheikh Nasser Bin Hamad Al Khalifa, former Qatari Ambassador to the U.N. and to the U.S.

“And it used to be very inclusive, very open, respectful of all its political elements – Kurdish, Arab Sunni, Arab Shia, Arab Christian and others."

But not anymore, he told VOA, stressing that his remarks are his own and not representative of any government.

“Everybody was expecting something big to happen in Iraq when Maliki came back as Iraqi prime minister four years ago,” Al-Khalifa said. “Instead of really opening up Iraq and making it a model for the religions, Maliki became beholden to the Iranians’ strategic goals in the region, i.e., to dominate the whole Middle East and the Gulf, and he created a sectarian state – as a matter of fact, an Iranian state within Iraq – because even Shi'ite Arabs suffered under him a lot.”

Al-Khalifa also said Maliki squandered hundreds of billions of dollars that should have been spent on improving Iraq’s faulty infrastructure. Meanwhile, sectarian violence was building, especially in the northeast tribal areas of the country. When Iraqi security forces cracked down on Sunni protesters in Anbar province in April, tensions spiraled out of control.

While it may have seemed as if ISIL came out of nowhere, observers in the region saw it coming months ago, Al-Khalifa said.

The Qatari diplomat also warned that U.S. intervention in Iraq on behalf of Maliki’s government could be seen by those tired of Western intervention as “a new crusade” aimed at destroying Arabs and Islam. And Maliki, with help from Iran, could read it as green light to stay put and continue his sectarian politics.

Sectarian Showdown?

President Obama also said Thursday the U.S. will head up a diplomatic effort with Iraqi and regional leaders to support stability in Iraq.

Secretary of State John Kerry will travel to the Middle East and Europe this weekend for consultations with U.S. allies.

David Ottaway, senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and a former Washington Post Middle East correspondent said he is doubtful that Maliki himself can achieve political unity. Tensions between the Iran-backed government and Iraq’s Sunnis have been simmering for far too long.

“The Sunnis have smarted ever since they lost power in Baghdad in 2003, and over time it’s just gotten worse and worse,” Ottaway said. “I don’t see how Maliki will get any Kurds or Sunnis at this point to join in a coalition government.

"I think it’s rather headed in the opposite direction – towards a Sunni-Shia shootout.”

With better information about what ISIL is doing and where, the U.S. can better support the Iraqi military in countering the threat of Sunni Islamist forces. That may be good news for the Iranian-backed Maliki government in Iraq, but is not expected to sit well with Sunnis outside of Iraq – in particular, Sunni monarchies of Saudi Arabia, Qatar and other Gulf countries.

Assigning blame

“This is very much a situation of competing narratives,” said Salman Sheikh, director of the Brookings Doha Center and fellow at the Saban Center for Middle East Policy.

“The Maliki government, the Assad government, as well as Iran, are seeing this very much as a fight between elected governments and Sunni extremists, al-Qaida extremists," he said.

“On the other side, you’ve got a narrative which is very much about the grievances that are being done to the Sunnis' heartland, particularly in Iraq by Maliki, and of course by a minority in Syria to the majority Sunni population,” Sheikh said.

Iraqi Prime Minister Nouri Al-Maliki has blamed Saudi Arabia for supporting the Sunni extremists with weapons and cash. But Saudi and the other Gulf countries throw the blame right back at the Iraqi leader, a Shi'ite, saying his own “sectarian and exclusionary policies” led to the current crisis.

They also criticize the United States for its ongoing support of Maliki, warning that if the U.S. continues to back him, it could ignite a regional sectarian war.

The situation is therefore enormously complex, Sheikh said, and one that places the United States in a political quandary.

Crisis was predictable

“Iraq is a mosaic of cultures, histories, ethnicities, religions and sects,” said Sheikh Nasser Bin Hamad Al Khalifa, former Qatari Ambassador to the U.N. and to the U.S.

“And it used to be very inclusive, very open, respectful of all its political elements – Kurdish, Arab Sunni, Arab Shia, Arab Christian and others."

But not anymore, he told VOA, stressing that his remarks are his own and not representative of any government.

“Everybody was expecting something big to happen in Iraq when Maliki came back as Iraqi prime minister four years ago,” Al-Khalifa said. “Instead of really opening up Iraq and making it a model for the religions, Maliki became beholden to the Iranians’ strategic goals in the region, i.e., to dominate the whole Middle East and the Gulf, and he created a sectarian state – as a matter of fact, an Iranian state within Iraq – because even Shi'ite Arabs suffered under him a lot.”

Al-Khalifa also said Maliki squandered hundreds of billions of dollars that should have been spent on improving Iraq’s faulty infrastructure. Meanwhile, sectarian violence was building, especially in the northeast tribal areas of the country. When Iraqi security forces cracked down on Sunni protesters in Anbar province in April, tensions spiraled out of control.

While it may have seemed as if ISIL came out of nowhere, observers in the region saw it coming months ago, Al-Khalifa said.

The Qatari diplomat also warned that U.S. intervention in Iraq on behalf of Maliki’s government could be seen by those tired of Western intervention as “a new crusade” aimed at destroying Arabs and Islam. And Maliki, with help from Iran, could read it as green light to stay put and continue his sectarian politics.

Sectarian Showdown?

President Obama also said Thursday the U.S. will head up a diplomatic effort with Iraqi and regional leaders to support stability in Iraq.

Secretary of State John Kerry will travel to the Middle East and Europe this weekend for consultations with U.S. allies.

David Ottaway, senior scholar at the Woodrow Wilson Center and a former Washington Post Middle East correspondent said he is doubtful that Maliki himself can achieve political unity. Tensions between the Iran-backed government and Iraq’s Sunnis have been simmering for far too long.

“The Sunnis have smarted ever since they lost power in Baghdad in 2003, and over time it’s just gotten worse and worse,” Ottaway said. “I don’t see how Maliki will get any Kurds or Sunnis at this point to join in a coalition government.

"I think it’s rather headed in the opposite direction – towards a Sunni-Shia shootout.”