Nearly 120,000 Afghan nationals who were evacuated after the Taliban takeover on August 15 are now in temporary camps in locations around the world, starting a months- or yearslong process to resettle abroad.

The immigration paths of these displaced Afghans vary widely, depending on their previous jobs, their status as vulnerable Afghans under Taliban rule and the locations they ended up in after evacuating.

On Thursday, U.S. President Joe Biden signed a federal spending bill that included $6.3 billion to help evacuate and resettle in the United States what the administration projects will be 95,000 Afghan evacuees in the next year.

Of the estimated 120,000 Afghans evacuated, 64,000 are already in the United States. Their first stop is at U.S. military bases, where their relocation paperwork is being processed while they are given access to medical screening and vaccinations.

Tens of thousands of other Afghans are being housed in temporary facilities in third countries while their applications are being processed.

And an unknown number of potential migrants remain in Afghanistan, where many are still trying to complete the logistical and bureaucratic steps that would let them leave.

Here are the different groups of evacuated Afghans and how their statuses affect their immigration paths.

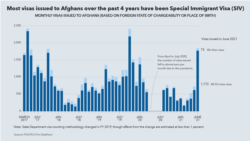

Special Immigrant Visa (SIV) recipients

Afghans who hold SIV status have worked for the U.S. government or contractors in Afghanistan for at least a year. They went through a 14-step SIV application process, which can take several years to complete. SIV status also covers applicants' immediate relatives.

Before traveling to the U.S., SIV holders will receive documents to present to Customs and Border Protection (CBP) once they arrive in the United States. After that, permanent residency cards, also known as green cards, are mailed to the addresses they provided.

Pending SIV status

Under Operation Allies Welcome, Afghans who had not finished the SIV application process at the time they were evacuated are admitted to the United States under “humanitarian parole” while their SIV applications are adjudicated.

Once paroled, the Afghans can also apply for a different immigration status through U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS).

Other paths to permanent residency include work or family sponsorship, according immigration lawyer Dean Murray.

“There is a category where an employer can sponsor [a worker], but you have to fulfill the [permanent labor] requirement, meaning there has to be a labor certification. You don't want to displace a U.S. worker,” Murray said. “Or they can be a beneficiary of the family-based [categories], and they can adjust that way. But in the family base, you have a long wait time unless you're an immediate relative.”

The family reunification path can take one to five years or longer depending on the individual circumstances.

Humanitarian parolees

Afghans who were not SIV applicants at the time of their evacuation qualify for “humanitarian parole.” Under the Immigration and Nationality Act, certain individuals can enter and stay in the U.S. without visas temporarily because of “urgent humanitarian reasons,” but they are ineligible for permanent residency.

According to DHS, Afghan nationals who are paroled into the country will have conditions placed on their statuses, including medical screening, vaccination requirements and other reporting requirements to U.S. immigration authorities. If they fail to follow the conditions, the government can deny their applications for work authorization and “potentially” terminate their parole and deport them.

Parolees can apply for asylum in the United States, the same avenue open to some migrants arriving at the U.S.-Mexico border. But refugee advocates call it a “very bureaucratic and inefficient way” to help resettle Afghans because of the long timetable for completing the process.

Going through “that whole system doesn't seem like the best way to address a population [of evacuees] that, all of whom, will likely qualify for asylum,” said Melanie Nezer, a spokesperson for the immigrant advocacy group HIAS.

Afghan nationals may claim asylum immediately, or up to one year after their arrival in the United States. After filing, each applicant will then meet with an asylum officer who approves or rejects the claim. If an asylum case is not approved, it is sent to an immigration judge.

Refugees in third countries

In early August, the State Department announced the new P-2 Direct Access Program for Afghans who worked for the U.S. government, U.S.-based nongovernmental organizations or American news organizations.

The program provides a straightforward path to the refugee resettlement process but the refugees must, on their own, first reach a third country where they can contact the State Department to begin the resettlement process.

According to DHS, the State Department is managing referrals to the refugee program, but there is no direct contact with the U.S. government prior to an applicant's departure from Afghanistan.

Approved applicants will then receive travel documents and resettle in the United States.

Under U.S. immigration law, refugees may apply for green cards to become permanent residents after one year in the United States. After five years of permanent residency, they can apply for U.S. citizenship.

Backlogs could delay timetable

Aid groups say vulnerable Afghans can state a fear of persecution in their home country in order to remain in the United States, but the U.S. asylum system is heavily backlogged with applicants coming through the U.S.-Mexico border. Processing delays for Afghans could stretch for four to five years.

Refugee advocates are urging the Biden administration to work with Congress to ensure that, regardless of their immigration status, a pathway to permanent residency exists for all Afghan nationals.

“Congress must pass an Afghan Adjustment Act to establish a road map to citizenship for Afghans," Paul O’Brien, executive director at Amnesty International USA, said in a statement.

According to DHS, from August 17 through September 20, about 64,000 Afghan evacuees arrived in the U.S.

Of those, approximately 7% are U.S. citizens, 6% are Lawful Permanent Residents, and 87% are Afghan nationals with SIV status or pending applications, U.S. visa holders and other vulnerable Afghans. Only 3% had the SIV process completed.

In response to a VOA question, General Glen VanHerck, head of U.S. Northern Command, said 14,000 Afghans remained in the United States European Command region, awaiting travel to the U.S. VanHerck said U.S.-bound flights could start next week.

VOA's Carla Babb contributed to this report.