After nearly 20 years of war, the United States and its allies left Afghanistan in August 2021, evacuating nearly 130,000 people in the chaotic last weeks in Kabul.

Through Operation Allies Welcome, about 88,500 Afghan nationals arrived in the U.S. and resettled in communities across the country.

But seven months later, the Biden administration faced another humanitarian challenge. The Russian invasion of Ukraine in February 2022 sparked another refugee crisis. Since the start of the war, more than 7.8 million refugees have fled Ukraine.

Although the U.S. was quick to announce a response for Ukrainian refugees, both Ukrainians and Afghans must navigate the same U.S. immigration system.

Here’s a look at the U.S. immigration realities for Afghans and Ukrainians, and the various paths they have used to enter the United States.

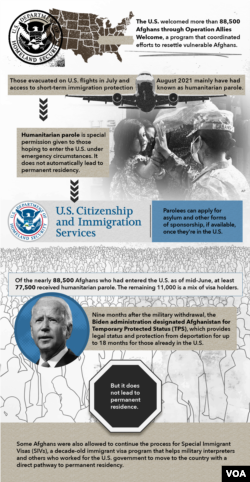

Afghans

The U.S. has welcomed more than 88,500 Afghans through Operation Allies Welcome, a program that coordinated efforts to resettle vulnerable Afghans.

These Afghans were evacuated on U.S. flights in July and August 2021 and mainly have received a short-term immigration protection known as humanitarian parole.

Humanitarian parole is given to those hoping to enter the U.S. under emergency circumstances. While it does not automatically lead to permanent residency, parolees can apply for legal status through the asylum process or other forms of sponsorship, if available, once they're in the U.S.

Of the nearly 88,500 Afghans who had entered the U.S. as of mid-June, at least 77,500 received humanitarian parole. The remaining 11,000 is a mix of visa holders.

Afghans still in Afghanistan who are hoping to receive a visa must travel to a U.S. embassy—the closest are in Qatar, Pakistan or the United Arab Emirates—for an interview.

Or they can apply to U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services (USCIS) for humanitarian parole, the safest way is online. But they must pay a $575 fee and prove they were persecuted by the Taliban. The fee applies to everyone seeking humanitarian parole. Applicants can ask for a fee waiver but need to show proof of financial hardship to the U.S. government.

More than 40,000 Afghans living outside the U.S. have submitted humanitarian parole applications since the U.S. withdrawal from Afghanistan. About 500 of those applications have been approved.

According to the Migration Policy Institute (MPI), fewer than 5,000 of the 40,000 cases were fully adjudicated by mid-June 2022, and 297 were approved.

Nine months after the military withdrawal, the Biden administration designated Afghanistan for Temporary Protected Status (TPS), which provides legal status in the U.S. and protection from deportation for up to 18 months. It also provides work permits for people to work legally in the country. And it can be extended.

But it does not lead to permanent residence.

Some Afghans were allowed to continue the process for Special Immigrant Visas (SIVs), a decade-old immigrant visa program that helps military interpreters and others who worked for the U.S. government to come to the U.S. with a direct pathway to permanent residency.

The State Department has hired more staff members to process SIVs, but the MPI says adjudication remains slow.

Since the start of the Biden administration through November 1, 2022, the State Department has issued nearly 19,000 SIVs to principal applicants and their eligible family members.

There are about 15,000 SIV principal applicants who are waiting for their visa interview, the step before being issued an SIV. About 48,000 individuals have submitted all documents and are waiting to be processed.

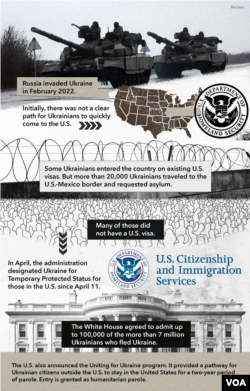

Ukrainians

When Russia invaded Ukraine in February, it started an exodus not seen since World War II.

Initially, there was not a clear path for Ukrainians to quickly come to the U.S. Though most Ukrainians were seeking refuge in other countries in Europe, some pursued safety in the U.S.

Some Ukrainians entered the county on existing U.S. visas. But more than 20,000 Ukrainians traveled to the U.S.-Mexico border and requested asylum. Many of those did not have a U.S. visa.

Two months after Russia’s invasion, the Biden administration designated Ukraine for Temporary Protected Status and applied it to Ukrainians in the U.S. since April 11. The White House also agreed to admit up to 100,000 of the more than 7 million Ukrainians who fled Ukraine.

On April 21, 2022, the U.S. announced the Uniting for Ukraine program to provide a pathway for Ukrainian citizens outside the U.S. to stay in the U.S. for two years on humanitarian parole.

Uniting for Ukraine also allows U.S. citizens, green card residents and others with certain other immigration statuses to support Ukrainian refugees.

To apply, Ukrainians must have been a resident of Ukraine as of Feb. 11, 2022, and there is no application fee.

After launching Uniting for Ukraine, the Department of Homeland Security (DHS) announced it would no longer allow Ukrainians to enter the country through the U.S.-Mexico border by humanitarian parole.

Ukrainians already in the U.S. as of April 11 cannot apply for humanitarian parole under the program. They can, however, apply for TPS or the asylum program.

As of late November, the U.S. has allowed more than 180,000 Ukrainians to stay in the U.S. for a period of time through humanitarian parole, TPS or other forms of family sponsorship.

Afghans and Ukrainians

Both Afghans and Ukrainians can apply for admission to the U.S. refugee program.

Additionally, family members of Afghans or Ukrainians can file a petition to bring their loved ones to the U.S. They must be a citizen or a green card holder, and the process covers only direct relatives.

Afghans and Ukrainian who received humanitarian parole can apply for asylum unless another, long-term immigration protection is available to them.