Among the athletes representing the United States at the upcoming Rio Olympics in Brazil will be several new Americans - and they are soldiers in the U.S. Army.

Military service provides a fast-track to U.S. citizenship, and not just for soldier-athletes. Normally, a green card holder has to wait five years to apply to naturalize. But after the terrorist attacks of 9/11, Congress voted to allow immigrants in the military to apply as soon as they wanted.

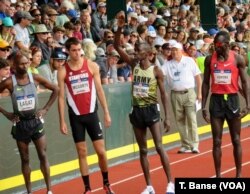

Because of this, Kenyan-born soldiers Paul Chelimo, Shadrack Kipchirchir and Leonard Korir could, and did, receive citizenship quickly - in time to compete for a spot on this year's U.S. Olympic team.

The cradle of champion runners

The Kenyan natives in the U.S. Army training program all come from the Rift Valley province. On those legs, Kenyans have dominated the Olympic medals podium in distance running for more than 20 years.

"In Kenya, running is like soccer in Brazil," explained Korir.

Kenyan-born runners also dominate the roster of the U.S. Army World Class Athlete Program (WCAP) track and field team. WCAP is open to everyone in the Army who can meet the tough entry standards.

Head coach Dan Browne guesses its popularity among Kenyan-American runners was spread through “word-of-mouth.” Korir, who will compete in the 10,000 meters in Rio, has his own theory.

"I think it is because of the passion. Many people in Kenya like to run. Many people here in America, they want to do other stuff... like football, soccer," he said.

In Rio, Korir will be competing against fellow-Kenyan runner Kipchirchir.

After the 27-year-old finance specialist qualified in the 10,000 meters during the Olympic trials earlier this month in Eugene, Oregon, Kipchirchir explained "It's not about me. It's all about all the soldiers that sacrificed their lives and dedication and hard work. I'm not going to let them down."

Chelimo won his spot on Team USA by finishing in the top three in the 5,000 meters.

After 12 laps around the track, the race came down to a furious sprint to the finish.

Chelimo recalled, "I was like, 'You know what, let it be what it can be.' So I decided to push."

A path to citizenship... and the Olympics

Chelimo, 25, is one of five Army soldiers to make the Olympic team in track and field this year. Four of them followed similar paths to get here. They were born and raised and started running in the highlands of Kenya. They got athletic scholarships to American universities. After college, they enlisted in the U.S. Army, which non-citizens with legal residency may do.

Chelimo signed up for four years in 2014 - with an eye on the Olympics.

"Actually, my main goal was to represent the United States. Being an Olympian is the best way to represent the United States. So as soon as I joined, I knew about WCAP," he said. "That was the best program because I could do my career as a soldier and also focus on my talent."

Browne, also the Army's head coach for track and field, is a former Olympian himself - competing in the 2004 Games in Athens - and a major in the Oregon National Guard on active duty. He says there was a good reason for the Army to create a unit where soldiers collect regular pay while focusing on training for upcoming world competitions such as the Olympics and Paralympics.

"They are great ambassadors for the Army," he said. "They represent sacrifice, determination, loyalty, commitment - all of our ethos."

It was Browne who convinced his superiors to let some of the Army runners relocate to his hometown of Beaverton, Oregon. That's far from the nearest Army post, but home to Nike world headquarters and a cadre of other professional runners to work out with.

Kipchirchir says training at the highest level while still attending to Army tasks, like making recruiting appearances, is not easy.

"You know the Nike athletes, their job is just running," he said. "They concentrate on just running. But ours, we are soldiers first, soldiers first."

Which country to represent?

In May, during a keynote address to a conference in London, the president of track and field's world governing body, the IAAF, raised the delicate issue of athletes switching national allegiance.

"I've asked our corporate governance review to look at this, to come back with a set of proposals," Lord Sebastian Coe said. "In the past, these transfer of allegiance requests have been, sometimes, a little flimsy and we need to address that.

"My instinct is that we need to settle upon a principle that if an athlete starts their international career competing for a particular country, they finish their career for a particular country," Coe continued. "This is a concern that's been expressed to me through all our continental associations."

The president of European Athletics, Svein Arne Hanson, said he planned to bring up the issue at the next IAAF Council meeting to be held on the sidelines of the Rio Olympics.

"We in European Athletics believe there is a need to look more closely at the appropriate conditions for a change in nationality and the length of time before eligibility is granted to compete," Hanson said in a statement.

Hanson acknowledged there is a range of personal reasons that drive athletes to switch allegiance, including refugee status.

U.S. soldier-athletes

Since the Army established its world class athlete training program in 1997, 65 soldier-athletes have competed at the Olympic and Paralympic Games.

This year, WCAP is sending 10 competitors to the Rio Olympics - four runners, a race walker, four marksmen and one competitor in modern pentathlon. In addition, an Army archer and a swimmer qualified for the Paralympic Games for physically-disabled athletes, which follow the Rio Olympics using the same venues.

The Rio-bound crew also includes a newly naturalized champion wrestler from Uzbekistan who is going to the Olympics as an alternate on the U.S. wrestling team.