HINKLEY, CALIFORNIA —

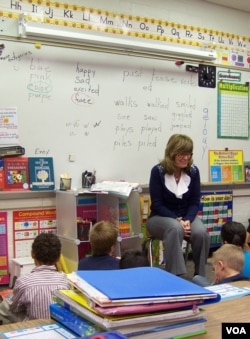

The first and second graders at the Hinkley School gather in pairs to practice their vocabulary words. It seems business as usual for now, but with so many families leaving town, the school is scheduled to close forever in June.

“We’re learning every day different areas the kids are moving to now and we’ve had many, many tears," said Sonja Pellerin, a teacher at the school. "Some people have lived here for generations, and it is turning families upside down.”

Hinkley is the California town made famous by the movie, Erin Brockovich. Twenty years ago, the California-based energy company Pacific Gas & Electric paid hundreds of millions of dollars to settle legal claims by residents that PG&E had poisoned their well water by improperly dumping industrial waste into the ground. But that landmark legal victory, which was recounted in the Julia Roberts movie, was not the end of the story.

Since then, the plume of groundwater contaminated with toxic hexavalent chromium, also known as chromium 6, has continued to spread. Now, Hinkley residents are leaving, and the town's future is uncertain.

But Hinkley School's future is not. With enrollment falling sharply for several years, education officials say they can’t afford to keep the school open.

Roberta Walker, who came to school to have lunch with her grandchildren, is angry that the PG&E energy company declined school officials’ request to buy the campus in order to keep it open.

“The school was the biggest, biggest part of the community," Walker said. "And they refused to admit that they were at fault for the decline in enrollment.”

In the 1990s, Walker was the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit by hundreds of Hinkley residents against PG&E for dumping cooling water from a natural gas compression plant south of town into unlined ponds. The waste, laden with toxic chromium 6, contaminated Hinkley’s groundwater wells, and the suit blamed the company for the increased incidence of cancer and autoimmune disease that followed.

The company settled. With her share of the money, Walker built new homes for herself and her daughters several kilometers from the contamination site. Now, chromium 6 has turned up in her well water again. Walker and her daughters are negotiating with PG&E to buy their homes.

“There’s still that little hope that the state will continue pushing along, but am I gonna do it?" she said. "And once I leave, and once I get out of here, am I going to? No. I’m not. I’m tired. I’m done.”

PG&E has already agreed to buy out a third of Hinkley’s residents. Company spokesman Jeff Smith has said repeatedly over the years that PG&E wants to make sure Hinkley survives. But that’s getting more complicated.

“We certainly remain committed to working with the people of Hinkley," Smith said. "If their preference is to have their property purchased and to depart from the community, we want to make sure we have that option available to them as well.”

At the national level, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has spent the past 5 years studying new limits on chromium 6 in the environment. The EPA released a draft assessment in 2010, but that study is still under scientific review. The agency says it would be inappropriate to revise national drinking water standards until the process is complete.

“Hinkley is an example of, even when you get a lot of attention, still we can be lacking, on a larger society level, standards that are protecting people,” said Renee Sharp, with the Environmental Working Group, a private research and advocacy organization.

Under state orders, PG&E is still trying to clean up its mess. It's been pumping millions of liters of contaminated water onto nearby alfalfa fields each year, to let microbes in the soil break down the poison. The company also is pumping ethanol into the ground to trigger a chemical reaction designed to neutralize the chromium. At a public meeting in October, project engineer Kevin Sullivan offered this encouragement.

“We’re making a lot of progress. We’ve cleaned up like 54 acres [22 hectares]," he said. "I understand that if it’s not your property, you know, [you’ll ask] ‘What have you done for me lately?’ But 54 acres is a lot of progress. ”

But it’s only a fraction of the environmental damage. Three years ago, state water quality officials estimated the contamination plume was a little more than four kilometers long. According to the most recent state report, it may now stretch more than 11 kilometers, and the state water quality board says it's spreading more than half a meter per day.

“It seems like the more we look, the more we’re finding, and it’s something that is scary for folks,” said the state water quality board's Lauri Kemper.

Frightening as the pollution is, Patsy Morris, 83, was determined to stay until recently. With Hinkley emptying out, she’s decided she has no choice but to leave, too.

“You get a bitterness about the whole thing," Morris said. "They’re just going to make this a big dustbowl, that’s all I can say about it. My friends are leaving, one way or another. It gets you, you know?”

PG&E estimates it take could another 40 years to clean up all of the chromium 6 pollution. That draws grim laughter from people in Hinkley. They predict that within 10 years, their community will be a ghost town.

“We’re learning every day different areas the kids are moving to now and we’ve had many, many tears," said Sonja Pellerin, a teacher at the school. "Some people have lived here for generations, and it is turning families upside down.”

Hinkley is the California town made famous by the movie, Erin Brockovich. Twenty years ago, the California-based energy company Pacific Gas & Electric paid hundreds of millions of dollars to settle legal claims by residents that PG&E had poisoned their well water by improperly dumping industrial waste into the ground. But that landmark legal victory, which was recounted in the Julia Roberts movie, was not the end of the story.

Since then, the plume of groundwater contaminated with toxic hexavalent chromium, also known as chromium 6, has continued to spread. Now, Hinkley residents are leaving, and the town's future is uncertain.

But Hinkley School's future is not. With enrollment falling sharply for several years, education officials say they can’t afford to keep the school open.

Roberta Walker, who came to school to have lunch with her grandchildren, is angry that the PG&E energy company declined school officials’ request to buy the campus in order to keep it open.

“The school was the biggest, biggest part of the community," Walker said. "And they refused to admit that they were at fault for the decline in enrollment.”

In the 1990s, Walker was the lead plaintiff in a lawsuit by hundreds of Hinkley residents against PG&E for dumping cooling water from a natural gas compression plant south of town into unlined ponds. The waste, laden with toxic chromium 6, contaminated Hinkley’s groundwater wells, and the suit blamed the company for the increased incidence of cancer and autoimmune disease that followed.

The company settled. With her share of the money, Walker built new homes for herself and her daughters several kilometers from the contamination site. Now, chromium 6 has turned up in her well water again. Walker and her daughters are negotiating with PG&E to buy their homes.

“There’s still that little hope that the state will continue pushing along, but am I gonna do it?" she said. "And once I leave, and once I get out of here, am I going to? No. I’m not. I’m tired. I’m done.”

PG&E has already agreed to buy out a third of Hinkley’s residents. Company spokesman Jeff Smith has said repeatedly over the years that PG&E wants to make sure Hinkley survives. But that’s getting more complicated.

“We certainly remain committed to working with the people of Hinkley," Smith said. "If their preference is to have their property purchased and to depart from the community, we want to make sure we have that option available to them as well.”

At the national level, the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) has spent the past 5 years studying new limits on chromium 6 in the environment. The EPA released a draft assessment in 2010, but that study is still under scientific review. The agency says it would be inappropriate to revise national drinking water standards until the process is complete.

“Hinkley is an example of, even when you get a lot of attention, still we can be lacking, on a larger society level, standards that are protecting people,” said Renee Sharp, with the Environmental Working Group, a private research and advocacy organization.

Under state orders, PG&E is still trying to clean up its mess. It's been pumping millions of liters of contaminated water onto nearby alfalfa fields each year, to let microbes in the soil break down the poison. The company also is pumping ethanol into the ground to trigger a chemical reaction designed to neutralize the chromium. At a public meeting in October, project engineer Kevin Sullivan offered this encouragement.

“We’re making a lot of progress. We’ve cleaned up like 54 acres [22 hectares]," he said. "I understand that if it’s not your property, you know, [you’ll ask] ‘What have you done for me lately?’ But 54 acres is a lot of progress. ”

But it’s only a fraction of the environmental damage. Three years ago, state water quality officials estimated the contamination plume was a little more than four kilometers long. According to the most recent state report, it may now stretch more than 11 kilometers, and the state water quality board says it's spreading more than half a meter per day.

“It seems like the more we look, the more we’re finding, and it’s something that is scary for folks,” said the state water quality board's Lauri Kemper.

Frightening as the pollution is, Patsy Morris, 83, was determined to stay until recently. With Hinkley emptying out, she’s decided she has no choice but to leave, too.

“You get a bitterness about the whole thing," Morris said. "They’re just going to make this a big dustbowl, that’s all I can say about it. My friends are leaving, one way or another. It gets you, you know?”

PG&E estimates it take could another 40 years to clean up all of the chromium 6 pollution. That draws grim laughter from people in Hinkley. They predict that within 10 years, their community will be a ghost town.