FILE - A recruiter talks with an applicant at a booth at a job fair at a shopping center in Beijing, on June 9, 2023. A record of more than one in five young Chinese are out of work, their career ambitions at least temporarily derailed by a depressed job market as the economy struggles to regain momentum after its long bout with COVID-19

Melody Xie thought 2024 would be the year for her to start the next chapter of her life as an adult in China: finding a job, getting married and eventually having children.

But after sending out hundreds of resumes and failing to pass two civil service exams, the 24-year-old college graduate remains unemployed and has had no choice but to move back in with her parents who live in the southern city of Guangzhou.

“It’s been a year since I graduated from university but I have no income, no savings and no social life,” she told VOA in a written response on November 28.

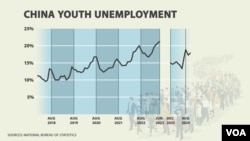

Like Xie, hundreds of thousands of young people in China have struggled to find ideal full-time jobs throughout 2024. While the Chinese government has introduced some fiscal measures to boost the sluggish economy in October, China’s youth unemployment remains high.

Since July, China’s unemployment rate for youth between 16 and 24 has remained above 17%. While some Chinese state media outlets claim the youth unemployment rate has improved since October, the economic downturn has been exacerbating China’s unemployment problem for several years, said Dali Yang, an expert on Chinese politics at the University of Chicago.

“There is a backlog of youths who were supposed to be joining the labor force over the last two to three years, but they didn’t do very well in the job market,” he told VOA by phone.

“As a new cohort of youth graduating from college each year, that makes the job market very tough for the college graduates,” he added.

In addition to the large number of unemployed college graduates in the job market, Li Qiang, executive director of China Labor Watch, told VOA that poor working conditions in the country are also discouraging many educated young people in China from looking for full-time jobs.

“Many Chinese businesses will ask employees to work 12 to 16 hours a day, and they expect employees to work six or seven days a week,” Li said.

“Most young people in China are not willing to accept these jobs with tough working conditions, so that has also led to an increase in youth unemployment rate,” he told VOA by phone.

Linda Liu, a 25-year-old former project manager at a tech company in China’s Guangxi province, said jobs in some rural towns in China often offer very poor pay and almost no benefits.

“After being laid off from my job at a tech company in Guangzhou at the beginning of 2023, I moved back to my hometown in Guangxi province and soon found a job there,” she told VOA in a written response.

“But since the pay was very low and I can only take four days off each month, I quit after less than six months,” Liu added.

While some young Chinese are still looking for jobs, others have decided to “lie flat” or quit without backup plans.

“After being laid off in 2021, I left Beijing and moved to the southwestern Yunnan province for two years,” Celine Liu, a 26-year-old former law firm clerk, told VOA in a recorded response.

“At the time, I wanted to pull myself away from the hectic lifestyle in the big city and figure out what I wanted to pursue in my life. But after moving back to Beijing earlier this year, I realized I could no longer adapt to life in the big city, and that has also affected my ability to do well in job interviews,” she added.

The idea of “lying flat” also denotes a laid-back lifestyle that rejects intense competition and societal expectations. In recent years, many young Chinese people have chosen to “retire” to rural parts of the country with a lower cost of living to cope with the ongoing unemployment challenges. Some of them turn to e-commerce as a source of income.

Others see quitting without a backup plan as an opportunity for them to slow down and enjoy life.

“Many young people in China, including myself, follow the typical pattern of entering college, finding a job after graduation, getting married and having children, but we often don’t know what kind of future we want,” said Victor Wang, a 26-year-old former engineer in the Chinese city of Zhejiang.

“After quitting without a backup plan, I finally have a chance to take care of my physical and mental health, and it finally feels like I’m in control of my life,” he told VOA in a written response.

As the youth unemployment rate remains high in China, Ye Liu, an expert on international development at King’s College London, told VOA, young people in China might “diversify” their work patterns.

“More young people [will engage] in freelancing, part-time employment and [work] multiple jobs,” she said.

China will host an annual economic work conference this week and youth unemployment is expected to be one of several topics discussed by top Chinese officials during the event.

Discussion of the topic remains sensitive on the internet in China and social media platforms.

Last week, a commentary about China’s weak consumption, unemployment and “dispirited” youth by Gao Shanwen, chief economist of China’s state-owned SDIC Securities, was removed by China’s internet censors.

Additionally, access to Chinese economist Fu Peng’s video social media account was blocked after he commented on China’s weaker consumption at a conference in September.

The Chinese government has introduced some measures to boost employment opportunities for college graduates, including rolling out campus recruitment activities and increasing job placement rates for unemployed youth. China’s state news outlet, People’s Daily Online, reported more than 1,000 employers from around the country “are expected to offer more than 30,000 education-related positions.”

However, Li at China Labor Watch said unless the Chinese authorities try to fundamentally improve working conditions and strengthen protection for workers’ benefits, China’s youth unemployment problem is unlikely to improve within the next five years.