The International Atomic Energy Agency, or IAEA, has offered a final endorsement of Japan’s plan to release treated nuclear wastewater from its crippled Fukushima Daiichi power plant into the Pacific Ocean.

It’s a move that Tokyo hopes will help allay concerns held by regional partners as well as its own citizens, including fishermen who have been adamantly opposed to it.

From Tokyo on Tuesday, IAEA Director General Rafael Grossi said Japan’s proposed plan was consistent with the agency's safety standards with “negligible radiological impact on the environment [anticipated], meaning the water, fish and sediment.”

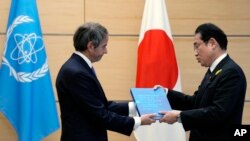

He presented the final review that had been initiated at Tokyo’s request in 2021, to Japanese Prime Minister Fumio Kishida, who will make the final call on how soon the controversial discharge will begin.

The entire process is expected to take three to four decades, given the massive amount of radioactive water sitting in about 1,000 tanks on Japan’s east coast. Kishida promised the sea release would proceed only if it were not harmful to the health of humans and of the environment.

“Japan will continue to provide explanations to the Japanese people and to the international community in a sincere manner,” he told media on Tuesday, sitting side by side with Grossi, “based on scientific evidence and with a high level of transparency.”

The IAEA’s green light, which culminates a two-year investigation, was widely anticipated. The U.N. watchdog had cleared the submitted methodologies and data on six previous occasions.

Operator Tokyo Electric Power Company (TEPCO) plans to treat, dilute and release – in controlled amounts – water that was used to cool the fuel rods of Fukushima units one, two and three, after reactor cores of all three melted down soon after the March 2011 earthquake ensuing tsunami. The event was considered the world’s worst nuclear disaster since the Chernobyl crisis in 1986.

A pumping and filtration process – dubbed the Advanced Liquid Processing System, or ALPS – will remove dozens of radionuclides from the contaminated water. Tritium, which cannot be removed from such a large volume of water, will be diluted to levels significantly below World Health Organization standards (to less than 1,500 becquerels per liter) before being released into the Pacific Ocean, according to Tokyo.

Supporters of the water release plan underline the urgency of the project, as TEPCO says it will run out of space for additional contaminated water by the first half of 2024. Currently, more than a million tons of radioactive water sit in the tanks in an archipelago that is no stranger to natural disasters.

Critics of the plan, including those in China, South Korea, and Pacific Island nations, raise the lack of full data sets for a proper evaluation to be made on safety. They’ve expressed concern over potential long-term dangers that lurk behind radionuclides that have half-lives ranging up to centuries and their unknown impact to the marine ecosystem and seafood.

China’s foreign ministry, soon after the IAEA’s announcement on Tuesday, expressed strong regret over the “hasty” approval, and forewarned Japan would have to bear all of the consequences should it move forward with its wastewater release plan.

As part of his four-day Japan visit, Grossi will open a new IAEA office at the Fukushima nuclear power plant site on Wednesday. He said the nuclear watchdog will keep a permanent presence to review, monitor and assess activity by Japan’s decommissioning project for decades to come.

Lingering doubt

Grossi comes to the East Asia region amid a significant amount of skepticism.

The IAEA chief will travel to South Korea on Friday to personally explain the task force’s findings, followed by visits to New Zealand and the Cook Islands. The Cook Islands chairs the Pacific Islands Forum (PIF), which has communicated the bloc’s “grave concerns” to Japan over the years and even commissioned its own expert review of the Fukushima wastewater release plan.

Noticeably absent on Grossi’s tour, however, is China, which has raised its voice in the run-up to the IAEA’s green light.

The U.N. agency’s endorsement should not be a “pass” for Japan to release its treated wastewater into the Pacific Ocean, Beijing warned on Tuesday. The IAEA’s mandate is limited to reviewing one option put forth by Tokyo, Foreign Affairs spokeswoman Mao Ning noted, and that it “cannot prove that the ocean discharge is the… safest and most reliable option.”

More than eight out of 10 people polled in 11 countries in the Pacific region – including China, South Korea, the Philippines, Singapore, Australia and New Zealand – held negative views of “Japan’s discharge of nuclear-contaminated water,” claimed state-run Chinese media the Global Times, citing its own study ahead of the IAEA announcement.

In South Korea – where the Yoon Suk Yeol government has prioritized a speedy rapprochement with Tokyo – eight of 10 people surveyed said they were concerned about the impact Japan’s water release will have on marine life.

Seafood consumption took a noticeable dive last month, prompting some politicians from Yoon’s political party to dine at fish markets, and in some cases, drink the water in the aquariums to drive home a point.

In Japan, 40% of those polled over the weekend said they were against the water release plan, surpassed by the 45% who expressed support.

It’s this matter of public perception that fishermen – particularly in the Fukushima area – fear will worsen an already bad situation.

South Korea maintains its ban on seafood from the affected region, and ruling party lawmakers on Monday emphasized that Tokyo should not expect that to change even with the IAEA’s endorsement.

“Even if it takes 10, 20, 30, 50 or 100 years, that’s not the point,” lawmaker Yun Jae-ok told reporters, indicating that first, trust needs to be earned. “The government holds firm the view that anything unsafe should not happen with regard to the people’s food.”

For the Pacific Island countries, whose livelihoods revolve around the ocean, it goes further. “This is not merely a nuclear safety issue. It is rather a nuclear legacy issue, an ocean, fisheries, environment, biodiversity, climate change, and health issue with the future of our children and future generations at stake,” wrote Henry Puna, head of the PIF, last week.

“Our people do not have anything to gain from Japan’s plan but have much at risk for generations to come,” Puna said.