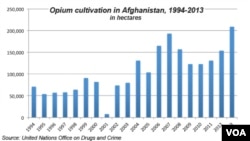

The United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime reported that opium poppy cultivation in Afghanistan has risen to a record high, possibly spurred on by farmers seeking to insure their incomes against uncertain conditions after the NATO troop pullout concludes in 2014.

In the report, released on Wednesday, the U.N. agency said the area of Afghanistan being cultivated for poppy production has risen to 209,000 hectares, higher than the previous peak of 193,000, reached in 2007.

It said this year's poppy harvest resulted in 5,500 metric tons of opium, a yield nearly 50 percent higher than last year. It also said farmers may be guarding against an uncertain future by increasing production of opium now.

Yury Fedotov, the executive director of the agency, called the rise in production "a warning" and "an urgent call to action" as Afghanistan begins to assume more control of its security. He said if the problem is not taken more seriously by international agencies, what he called "the virus of opium" could further reduce Afghanistan's stability.

Observers are also concerned that profits will go to warlords jockeying for power ahead of a presidential election next year. The expansion will come as an embarrassment to Afghanistan's aid donors after more than 10 years of efforts to wean farmers off the crop, fight corruption and cut links between drugs and the Taliban insurgency.

“The short-term prognosis is not positive,” said Jean-Luc Lemahieu, head of the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Afghanistan.

“The illicit economy is establishing itself, and seems to be taking over in importance from the licit economy.”

Afghanistan is the world's top cultivator of the poppy, from which opium and heroin are produced. Last year, it accounted for 75 percent of global supply and Lemahieu had previously said this year it might supply 90 percent.

The increase in the crop was caused by various factors including greater insecurity as foreign troops pull back in preparation for withdrawing next year, a high opium price last year and a growing lack of Afghan political will to tackle the problem.

That will is particularly weak as an April presidential election approaches, Lemahieu said. President Hamid Karzai cannot stand again, leaving the field open to a range of rivals, some linked to power-brokers who have profited from poppy in the past.

Some of the profits derived from the crop will be funnelled off by the Taliban to fuel their insurgency. Western officials privately accuse senior members of the Afghan state of also profiting.

The new figures are part of an annual assessment of opium production by the UNODC and the Ministry for Counter-Narcotics.

The report revealed that two northern provinces, Balkh and Faryab, were again growing poppy after being deemed poppy-free last year. Eradication fell by almost a quarter.

Stark Reminder

A gradual decrease in foreign funding as allies grow weary of helping war-racked Afghanistan has led to some members of the Afghan elites turning to poppy profits.

“When it comes to the illicit economy there is very little difference between the insurgents and the people on the other side,” Lemahieu said.

Afghanistan has a serious drug addiction problem but most of its output is smuggled abroad, particularly to Europe.

The British Foreign Office said the report was a “stark reminder” of the challenges facing Afghanistan in tackling the drugs trade.

“Lessons learned from other drug producing countries show that this will be a generational struggle against a complex global problem which needs a comprehensive approach,” a spokesman for the foreign office said.

Afghanistan's allies have tried to build infrastructure, develop markets and provide farmers with alternative crops, but insecurity and graft have largely stymied rural development while poppy eradication has been patchy.

A farmer in the southern province of Helmand, where almost half of Afghanistan's opium is grown and where British and U.S. forces have faced some of the fiercest fighting of the 12-year war, said he had no choice but to grow opium.

“We are lost,” said the farmer, Mullah Baran, who supports a family of twenty. “I do not know what is legal and what is illegal in Afghanistan. If I grow poppy, that is illegal, but if I pay a bribe, that is legal.”

Another farmer in Helmand said he had grown wheat last year on the encouragement of the provincial government but did not make enough to feed his family of 12, so switched back to poppy.

The farmer, Marjan, said he expected to harvest around 22 pounds of opium, which should earn him between $700 and $900, based on UNODC's price estimate.

“This year about 80 percent of farmers I know have grown poppy,” Marjan said.

In the report, released on Wednesday, the U.N. agency said the area of Afghanistan being cultivated for poppy production has risen to 209,000 hectares, higher than the previous peak of 193,000, reached in 2007.

It said this year's poppy harvest resulted in 5,500 metric tons of opium, a yield nearly 50 percent higher than last year. It also said farmers may be guarding against an uncertain future by increasing production of opium now.

Yury Fedotov, the executive director of the agency, called the rise in production "a warning" and "an urgent call to action" as Afghanistan begins to assume more control of its security. He said if the problem is not taken more seriously by international agencies, what he called "the virus of opium" could further reduce Afghanistan's stability.

Observers are also concerned that profits will go to warlords jockeying for power ahead of a presidential election next year. The expansion will come as an embarrassment to Afghanistan's aid donors after more than 10 years of efforts to wean farmers off the crop, fight corruption and cut links between drugs and the Taliban insurgency.

“The short-term prognosis is not positive,” said Jean-Luc Lemahieu, head of the U.N. Office on Drugs and Crime (UNODC) in Afghanistan.

“The illicit economy is establishing itself, and seems to be taking over in importance from the licit economy.”

Afghanistan is the world's top cultivator of the poppy, from which opium and heroin are produced. Last year, it accounted for 75 percent of global supply and Lemahieu had previously said this year it might supply 90 percent.

The increase in the crop was caused by various factors including greater insecurity as foreign troops pull back in preparation for withdrawing next year, a high opium price last year and a growing lack of Afghan political will to tackle the problem.

That will is particularly weak as an April presidential election approaches, Lemahieu said. President Hamid Karzai cannot stand again, leaving the field open to a range of rivals, some linked to power-brokers who have profited from poppy in the past.

Some of the profits derived from the crop will be funnelled off by the Taliban to fuel their insurgency. Western officials privately accuse senior members of the Afghan state of also profiting.

The new figures are part of an annual assessment of opium production by the UNODC and the Ministry for Counter-Narcotics.

The report revealed that two northern provinces, Balkh and Faryab, were again growing poppy after being deemed poppy-free last year. Eradication fell by almost a quarter.

Stark Reminder

A gradual decrease in foreign funding as allies grow weary of helping war-racked Afghanistan has led to some members of the Afghan elites turning to poppy profits.

“When it comes to the illicit economy there is very little difference between the insurgents and the people on the other side,” Lemahieu said.

Afghanistan has a serious drug addiction problem but most of its output is smuggled abroad, particularly to Europe.

The British Foreign Office said the report was a “stark reminder” of the challenges facing Afghanistan in tackling the drugs trade.

“Lessons learned from other drug producing countries show that this will be a generational struggle against a complex global problem which needs a comprehensive approach,” a spokesman for the foreign office said.

Afghanistan's allies have tried to build infrastructure, develop markets and provide farmers with alternative crops, but insecurity and graft have largely stymied rural development while poppy eradication has been patchy.

A farmer in the southern province of Helmand, where almost half of Afghanistan's opium is grown and where British and U.S. forces have faced some of the fiercest fighting of the 12-year war, said he had no choice but to grow opium.

“We are lost,” said the farmer, Mullah Baran, who supports a family of twenty. “I do not know what is legal and what is illegal in Afghanistan. If I grow poppy, that is illegal, but if I pay a bribe, that is legal.”

Another farmer in Helmand said he had grown wheat last year on the encouragement of the provincial government but did not make enough to feed his family of 12, so switched back to poppy.

The farmer, Marjan, said he expected to harvest around 22 pounds of opium, which should earn him between $700 and $900, based on UNODC's price estimate.

“This year about 80 percent of farmers I know have grown poppy,” Marjan said.