Turkey has been pressuring countries around the world to close or hand over control of schools linked to an influential Muslim cleric who was a close ally of President Recep Tayyip Erdogan before becoming his most worrisome foe.

Influential and polarizing, Fethullah Gulen has been accused of being behind a corruption probe of Erdogan’s government in 2013, which shattered their friendship. He also is accused of masterminding the July 2016 coup attempt in Turkey that left 250 people dead and 2,200 injured.

The reclusive 76-year-old cleric denies those allegations. He espouses a moderate form of Islam with an eye on political clout, and he built a financial empire in Turkey that included banks, media, construction companies and schools. He is reported to have 3 million to 6 million followers in Turkey, including high-ranking government and military officials.

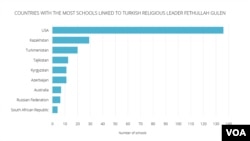

The schools began expanding internationally in 1993, and at one point there were Gulen-linked schools, cultural centers or language programs in more than 100 countries. In the United States, it’s the largest group of so-called charter schools, which receive tax funds. It has about 140 schools in 28 states, taking in more than $2.1 billion from taxpayers.

While some schools include teaching Islam, others reportedly have no religious content. Generally focused on math and science, the schools have earned praise from some parents, often because the quality of education is better than is generally available in some poverty-wracked countries.

Accused of hidden agenda

In Pakistan, for instance, they provide an alternative to the madrassas that have been accused of breeding extremism. The schools also are popular among Africa's middle class.

But they have been accused of having a hidden agenda: instilling a sense of deep loyalty among students that is part of an alleged long-term strategy of infiltrating governments, starting with Turkey, to spread a socially conservative agenda. The schools typically pursue visas for Turkish nationals — almost all men — to teach and even populate the school boards.

Gulen’s critics point to a video that surfaced in 1999 that purportedly came from a speech he gave.

“You must move in the arteries of the system without anyone noticing your existence until you reach all the power centers,” he said in the video. “If they do something prematurely, the world will crush our heads, and Muslims will suffer everywhere… You must wait for the time when you are complete and conditions are ripe, until we can shoulder the entire world and carry it.”

Gulen has said the video was manipulated and that the only purpose of the schools is education.

In the United States, there are allegations that some Gulen schools were involved in improper contracting and ordered teachers to kick back part of their salaries to the organization. While the FBI wouldn’t say if it is investigating the schools, there have been several news reports saying they were being probed, going back to 2011.

The Gulen organization, also known as the Hizmet movement, denies those accusations.

“We are very disappointed that in a quest to consolidate power and cast aspersions on Mr. Gulen, the Erdogan regime has decided to target K-12 schools that provide education, opportunity and hope to tens of thousands of students around the world, many of whom lack access to quality education in a safe environment,” said Alp Aslandogan, executive director of the Alliance for Shared Values, a nonprofit that serves as a voice for cultural organizations affiliated with Hizmet.

“Especially in countries such as Nigeria, Pakistan and Afghanistan, where violent radical groups targeted girls attending schools, these schools have been offering life-changing opportunities to both boys and girls. These schools operate completely independent of Mr. Gulen, as he has said many times, and in targeting them, Erdogan is only intensifying his cruel crackdown and robbing young girls and boys of a chance for a better life.”

Extradition demands

The Turkish government wants Gulen extradited from the United States — he has lived in a guarded compound in the U.S. state of Pennsylvania since 1999. Turkey says his Fethullah Gulen organization (FETO) is a terrorist group.

Ankara has shuttered thousands of schools, foundations and organizations linked to Gulen since the coup attempt. Turkish authorities have fired more than 100,000 government workers alleged to have ties to Gulen, and imprisoned about 50,000 people. Five hundred people, including top army generals, are on trial for Gulen links; Gulen himself is being tried in absentia.

The campaign against Gulen’s enterprises has expanded outside the country, too. On virtually every foreign trip by Erdogan, reports have emerged that he has pressed for Gulen schools to be closed or handed over to a Turkish foundation.

“These schools are one of the ways for FETO to finance its operations,” an official at the Turkish Embassy in Washington, D.C., told VOA. “They are a source of money. They can also be used as a source to recruit followers.”

The Turkish effort has resulted in the closure of schools in more than a dozen countries.

Turkey has begun denying visas to Kyrgyzstan citizens who study at schools affiliated with the Gulen movement; their families also are being denied.

Kyrgyzstan’s Ministry of Education and Science responded by saying the restriction was an attempt to discredit the educational institutions known as Sapat.

“Placing Sapat schools on the same footing as terrorist organizations and imposing certain sanctions on students and members of their families only on the grounds that they are studying in Sapat schools are unacceptable and the statements of Turkish officials are irresponsible,” the ministry said.

In Saudi Arabia and Malaysia, Turkish teachers and staff have been deported to Turkey, where they appeared likely to be arrested.

In February, Turkmenistan court sentenced 18 men to up to 25 years in prison — and confiscated their property — on offenses relating primarily to incitement to social, ethnic, or religious hatred and involvement in a criminal organization. Most were affiliated with Gulen schools.

Rights groups have called on the Turkmen government to free the men and quash their sentences.

“The way Turkmenistan’s courts prosecuted and tried these men bears no resemblance to justice,” said Rachel Denber, deputy Europe and Central Asia director at Human Rights Watch.

Ankara turning up the heat

During his visit to Albania in 2015, Erdogan asked authorities to close down the network of Turkish colleges that was the biggest private educational group in Albania. Since the failed coup, the pressure from Ankara has increased.

Several countries, including Angola and Uzbekistan, have cited unspecified “national security reasons” in shutting down Gulen schools and expelling the Turkish staff and their families.

Some countries appeared to choose closure rather than get involved in the hassles of overseeing a switch in who runs the schools.

Rwanda’s Ministry of Education ordered the Gulen-affiliated Hope Academy to close on June 2, just over two months after it had been granted permission to open. The ministry cited Turkey’s request to transfer control of the school to a Turkish foundation.

Other countries have resisted Turkey’s pressure. While accreditation was halted for one school in Georgia, at least six others remain open, with some education experts urging the country to defend its national interests because the schools have good reputations. But several schools are said to be likely transferred to the Turkish-government-owned Maarif Foundation, sources told VOA.

On Friday, Georgia's education ministry announced plans to shutter the Gulen-linked Demirel College in Tblisi, and possibly extradite the school's director, Mustafa Emre Chabuk, at Ankara's request.

Any move toward extradition, said Levan Asatiani, a regional campaign director for Amnesty International, will represent a criminal act.

"According to international law, it is prohibited to transfer a person to a state where this person is more likely to be subjected to torture, inhuman treatment or other serious human rights violations," he told VOA, adding that Georgian legislation prohibits extradition of a person in this situation.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, some Gulen schools work with the nation’s Bosna Sema educational institutions, which employ about 500 Turks. Turkish Ambassador CIhad Erginay urged the government to close down the schools, calling Gulen’s movement a terrorist organization.

VOA's Africa, East Asia Pacific, Eurasian, South and Central Asia divisions contributed to this report. Ani Chkhikvadze of VOA's Georgian Service contributed reporting.