Turkey’s Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan is in North Africa this week in what he is calling an expression of partnership with the emerging democracies of Egypt, Libya and Tunisia. His trip coincides with a critical decline in relations with Israel and an attack on the Israeli embassy in Cairo - as well as next week’s Palestinian bid for statehood at the United Nations. Erdogan’s “Arab Spring” tour and recent public statements have raised concerns in some quarters that Turkey is looking to create an alliance with Egypt that could be hostile to Israel - and, in a much more general sense, is indicative of what some have termed “neo-Ottomanism.”

Until recently, Turkey and Israel had been friendly. The thaw in relations, before they turned sour, dates back to 1949. That was the year Turkey formally recognized the Jewish state. Their friendship began to cool after the 2008-2009 Gaza war, and it was further strained by Israel’s 2010 raid on a Turkish aid ship to Gaza, which resulted in the deaths of nine Turkish activists onboard.

After a year-long investigation, the U.N. on September 2 concluded that Israel had acted with “excessive and unreasonable force,” in spite of “organized and violent resistance” by passengers. The world body encouraged Israel to make an appropriate statement of regret.

Erdogan has expressed anger and dismay with Israel’s refusal to apologize for the attack. Consequently, Turkey suspended military trade with Israel, expelled top Israeli diplomats, expressed support of the Palestinian bid for statehood and vowed to provide naval support for any future aid flotillas to Gaza. Erdogan has also warned that he is prepared to order his navy to escort future aid flotillas to Gaza.

Islamist Trend?

Ankara’s row with Israel, viewed in the context of Turkey’s refusal to participate in sanctions against Iran and its friendships with Syria and Sudan, has generated broader concerns that Turkey may realigning its political interests along Islamist lines and that the crisis with Israel is a part of a predetermined strategy of Islamization.

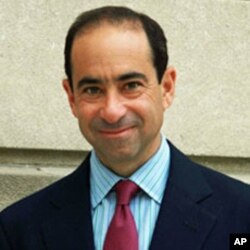

Michael Rubin is a Middle East scholar at the Washington, D.C.-based American Enterprise Institute (AEI). He accuses Turkey of delibaretely “whipping up” sentiments against Israel. “It wants to leverage that both domestically, in terms of its own politics, and also Turkey is making a claim for leadership of the Islamic world."

It should be noted that Turkey has been a staunchly secular state since 1928, just after the modern nation’s founding when a constitutional amendment was passed removing Islam as the state religion. Secularism and the removal of Ottoman era Islamic legal codes was a major priority of modern Turkey’s founder Mustafa Kemal Ataturk. The Constitution currently states that Turkey is a secular democratic republic.

Rubin believes it is no coincidence that Prime Minister Erdogan will this week address Arab foreign ministers. “Turkish foreign policy is consciously being driven toward more Islamic leanings,” he said, “and this is seen not only in the current situation, but this goes back to the diplomatic capital which Turkey is willing to expend in order to get the leadership of the Organization of the Islamic Conference (OIC).”

The 56-member OIC, the second largest intergovernmental organization in the world, is currently headed by Turkish academic and diplomat Ekmeleddin Ihsanoglu, who recently condemned the U.N. report on the Israeli raid of the Gaza flotilla for what he called a “whitewash” of Israel’s actions.

However, Erdogan declares himself to be an avowed advocate of secularism. In an interview aired by the Egyptian satellite channel Dream TV Monday, Erdogan expressed hopes that Egypt would choose a secular over an Islamic government, similar to the Turkish model. He also stressed his conviction that secularism is not incompatible with Islam.

Dr. Ian Lesser, executive director of the German Marshall Fund of the United States Transatlantic Center (GMF) in Brussels, does not share Rubin’s perspective. “There’s no question that a more traditional, somewhat more religious outlook is part of the Turkish world view today…the world view of the leadership, the world view of the public.” That is one of the reasons, he says, that the AKP government has been re-elected - several times.

“On certain issues, like the Palestinian question,” Lesser said, “there is clearly a strong sense of Muslim solidarity in play with Turkey’s public and leadership, and that does become a factor in the relationship with Israel - there’s no question about it.”

Policy Driven by the Pocketbook

Lesser says he does not see Islamism as the “single animating factor” in Turkish policy. He believes other factors animate Turkey’s shift away from the West - for one, Turkey’s stated goal of maximizing its regional influence through a “zero problems with the neighbors” policy. The analyst sees it as a balancing act that has resulted in billions of dollars in Arab investment into Turkey and that also positions Turkey as an important conduit of oil and gas between Europe and Asia.

Secondly, Lesser thinks that after the military no longer determines national strategy, public opinion counts more than ever. And most Turks, says he, these days vote by the pocket book.

The German Marshall Fund’s 2011 Transatlantic Trends survey, released this week, shows one in five Turks believe that on international issues, Turkey should cooperate with the Middle East rather than the West. Forty-three percent think that NATO is no longer essential; 53 percent have an unfavorable opinion of the European Union, and 43 percent consider Middle Eastern countries to be more important to Turkey’s economic interests than European countries.

Thus, says Lesser, business is the key dynamic in Turkish policy: “Commercial interests, especially in the Middle East, but also in Russia and Europe.” Even Turkey’s refusal to sign onto sanctions against Iran and its relationship with Syria, said Lesser, were “driven more by Turkey’s commercial and security interests, than by any concept of Islamic solidarity.”

Using naval power to protect potential natural resources that Turkey may lay claim to in the future is also a factor. The U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) last year estimated that more than 122 trillion cubic feet of gas and around 1.7 billion barrels of recoverable oil lie under the so-called “Levant Basin Province.” These resources, says USGS Energy Resources Program Coordinator Brenda Pierce, are “bigger than anything the USGS has assessed in the United States.” Turkey has contested the gas search, saying that it does not take into consideration the rights of Turkish Cypriots on the divided island.

Many experts blame Europe for Turkey’s growing nonalignment with the West. The European Union has been sluggish about admitting Turkey as a member. With the EU struggling in the global economic downturn, Turks have begun to find membership less attractive, and Turkish exporters have turned to markets in the Middle East and North Africa, the Gulf, Russia and even Central Asia. This has resulted in a booming Turkish economy - and a boost to the country’s confidence as a global power.

What’s at Stake?

Earlier this month Turkey suspended all defense trade with Israel, worth hundreds of millions of dollars annually. The Turkish Statistical Institute, or Turkstat, says that in 2010, Turkey had exports to Israel worth $2.08 billion and imports amounting to $1.35 billion. First-quarter figures for 2011 show trade was up 40 percent from the same time last year.

In short, the two countries have a lot riding economically on their relationship. The fact Turkey clarified that it was breaking defense ties alone is a good indicator that it recognizes this fact.

“Certainly,” AEI’s Michael Rubin said, “Turkey as an ally is helpful to Israel.” He worries that the crisis between Turkey and Israel could not only damage their historic partnership, but threaten the stability of the entire Middle East. “While right now, we are limiting this to a war of words, if Prime Minister Erdogan carries through on his threats to deploy the Turkish navy in the Eastern Mediterranean, then we could go down a slippery slope to at least an accident that could lead to more instability in the region,” he said.

Lesser of the GMF says the U.S. has a strong strategic interests in maintaining a “triangular” relationship between itself, Israel and Turkey, especially considering the possibility of missile proliferation in Iran. The biggest challenge for the White House, says he, is that the US has less leverage than it would like over either Turkey or Israel.

That said, Lesser doesn’t believe that Israel and Turkey will ever return to a full normalization of the good relations they enjoyed a decade ago. The question now, says he, is how to avoid a relationship driven entirely by crisis management, rather than strategy.