Tuareg rebels in northern Mali are closer than ever to the autonomy they have sought since the 1960s.

The international community has watched with distress as Tuareg rebels, and a splinter group of Islamist extremists, have seized control of northern Mali following a chaotic military coup in the capital, Bamako, on March 22nd.

Rebels now control a trio of key northern outposts, Kidal, Gao and Timbuktu, that have eluded them for decades.

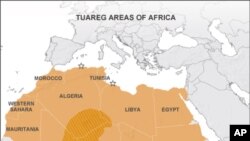

A separatist group, the National Movement for the Liberation of Azawad, or MNLA, claims the vast triangle of desert as its homeland, Azawad.

MNLA political spokesman Moussa ag Assarid said the group now controls the territory it wants. All that remains, he said, is to secure the border with Mali. He says they plan to create a secular, democratic state that will regroup all the ethnic groups in northern Mali, not just the Tuaregs. He said northern Mali is a different world from the south. He said they have tried to make do for the past 50 years but they have never truly been Malians. He said independence is now all they will consider.

The MNLA said Tuesday that it is stopping its advance and is now open to talks with the Malian government or regional authority, ECOWAS.

The MNLA is the latest incarnation of a rebellion that has raged on and off in Mali since independence, or even before that if you count Tuareg resistance to French colonial rule. This is the fourth major armed rebellion since 1963.

The Tuareg have their own language and a distinct matriarchal culture. It is the men who must cover their heads and faces with turbans that are said to ward off evil spirits and block out the harsh desert sun and wind.

Jeremy Keenan, an anthropologist and expert on the Tuareg at London's School of Oriental and African Studies, says arbitrarily-drawn colonial boundaries parceled the once nomadic tribes into various nations. "In Niger and Mali, they are majorities in their own regions and they have been marginalized. They have rebelled. It's been a pretty regular phenomenon. When they rebel, the governments usually attack the camps, the women and kids and all this sort of stuff. They feel aggrieved. They feel abandoned by the world and quite rightly they have been," he said.

The Malian government has defused previous rebellions with largely unkept promises for decentralization and development.

This rebellion, launched on January 17, is unique for several reasons.

The MNLA is a new group, created last October by veterans of previous rebellions as well as pro-Gadhafi Tuareg fighters returning from Libya. They brought with them the heavy arms and battlefield know-how that have catapulted the MNLA to a new level of military sophistication.

However, Keenan says the rebels are not invincible. "They are in a stronger position at the moment than they've ever been in the past but it's not the strongest on earth. They're not a vast army. They're small in number. Where are they going to get reequipped from? They haven't got an arsenal up the road. They haven't got Gadhafi behind them. They haven't got France that's going to step in and help. OK, they can help themselves to government armories in Gao and elsewhere when they get there. They know the desert. They can control the desert, that is until the helicopter gunships come in," he said.

Mali's much-condemned military junta has called for international help to stop the rebellion. Regional bloc ECOWAS has warned the rebels to halt their advance and says it is putting a military force on standby. France referred the situation to the U.N. Security Council.

Another unique element of this rebellion is the involvement of a small but visible extremist group, Ansar Dine, that wants shariah, or Islamic law, applied in northern Mali. The group, whose name means "Defenders of the Faith," broke off from the MNLA in March.

Residents of towns seized this past weekend say they saw rebels raising MNLA flags, as well as other fighters yelling "Allah akbar." News agencies report also seeing the Ansar Dine's black banner flying over Timbuktu Monday.

Ansar Dine is said to have ties to al-Qaida of the Islamic Maghreb, or AQIM.

French foreign minister, Alain Juppe, said Ansar Dine is cause for concern. AQIM, he says, has declared France a target and still holds six French hostages. He said France will not engage in direct military action against the rebels but could provide logistical support to any future intervention by regional authorities.

MNLA separatists are trying to shake off associations to Islamic extremism. The MNLA maintains that it is in a state of coexistence, and not cooperation, with Ansar Dine.

Experts say the two groups could come to blows once their perhaps uneasy alliance is no longer convenient. The power struggle would further destabilize northern Mali, where 200,000 civilians have already fled fighting, many to neighboring countries.

The Tuareg have run caravan trade routes through the Sahara for centuries. However analysts say the only goods moving along those routes now are drugs, guns and even people.

The vast swathe of desert is nearly impossible to police. It has become home to drug traffickers ferrying Latin American cocaine to Europe and al-Qaida linked terrorists. Analysts speculate that Tuareg tribes are not directly involved in these activities but are perhaps taxing and facilitating traffic moving through the desert.

MNLA spokesman Assarid said the MNLA plans to rid its territory of AQIM and traffickers. He said the Malian government has tried to damage the Tuareg's reputation by connecting them with these criminal elements. He said it was the government who gave these elements free rein, pointing to a rumored non-aggression pact between the government and AQIM.

Mali's northern deserts remain impoverished and underdeveloped. Growing desertification has made herding and farming difficult. Kidnappings and insecurity have killed off tourism, which was a key industry for the Tuareg in recent decades. Insecurity has also prevented exploration of potential oil, gas and mineral deposits.

The MNLA says that it can secure and ultimately develop the territory. That is a gamble the international community does not look prepared to make.

Head of the Michael S. Ansari Africa Center in Washington, J. Peter Pham, said a state of Azawad would not be economically viable today, though the Tuareg thrived in the centuries before colonialism. "That was their great moment in history when the trade routes ran through their area, when salt was worth its weight in gold. That era is gone. There may be some underlying resources up there, but in reality it is not a viable state and the last thing Africa, much less the Sahel, needs is another failed state," he said.

Pham said that failed state would create a vacuum where terrorists and traffickers already in the Sahara would flourish. "You've got an almost instant criminal state in the making," he said.

The coup has crippled Mali's already insufficient military capabilities. Mali's allies, including the United States, have cut off all military assistance until the junta restores constitutional order. The junta's moves in that direction have so far been limited and vague. Meanwhile, the rebels are consolidating their hold on the North.

Pham says the international community could be forced to choose between two priorities: steadfastly condemning the military overthrow and preventing further deterioration of the already fragile security situation in the Sahel.