U.S. Attorney General William Barr's canceled appearance before a congressional committee Thursday added to a long list of thorny legal conflicts and power struggles between America's executive and legislative branches.

Democrats, who control the House of Representatives, are demanding President Donald Trump's tax returns, financial documents related to the Trump family's business dealings, information about security clearances granted to Trump's relatives serving in the White House, and the release of the full, unredacted Russia report by special counsel Robert Mueller.

The Trump administration is largely refusing to cooperate, calling the lawmakers' requests political. Barr's absence before the House Judiciary Committee, where staff attorneys were to question him about the Mueller report, caused tempers to boil over and laid bare the full scope of an increasingly ferocious battle between House Democrats and the White House.

"President Trump has told Congress that he plans to fight all of our subpoenas," the panel's chairman, Democratic Rep. Jerrold Nadler of New York, said. "[T]he president of the United States wants desperately to prevent Congress, a coequal branch of government, from providing any check whatsoever to even his most reckless decisions. He is trying to render Congress inert."

Nadler added, "If we don't stand up to him [Trump] together, today, we risk forever losing the power to stand up to any president in the future.The very system of government of the United States — the system of limited power, the system of not having the president as a dictator — is very much at stake."

Congressional oversight or political weapon?

Republicans, meanwhile, accused Democrats of overstepping Congress' authority, propelled by a fundamental unwillingness to accept the legitimacy of Trump's victory in the 2016 presidential election.

"Yes, I believe in the power of Congress. I also believe in the rule of law," House Minority Leader Kevin McCarthy, a California Republican, said at a Washington Post forum. "They [Democrats] don't like the outcome of the Mueller report, I get it. They didn't like the outcome of the election, I get it. But I think it's time to have some adult supervision in the room and focus on what the American people want."

McCarthy argued House Democrats are investigating matters no previous Congress would have dared to probe. He compared Democrats' actions today with those of the previous Republican House majority during the former Obama administration.

"Did we [Republicans] ever request the personal finances of President Obama? Did we ever go after his family? Did we ever request his children? Did we ever go after his in-laws?" McCarthy said. "This is personal now. We've never taken it that far."

McCarthy's arguments were echoed by Trump's attorneys in a lawsuit filed to prevent banks from releasing financial documents subpoenaed by a House committee investigating Trump family businesses.

"The subpoenas were issued to harass President Donald J. Trump, to rummage through every aspect of his personal finances, his businesses, and the private information of the president and his family," the lawsuit contends. "No grounds exist to establish any purpose other than a political one."

House Financial Services Committee Chairwoman Maxine Waters promised to continue the probe.

"The president … will do everything that he can to shut down an investigation," the California Democrat said. "So he can file his lawsuits. So far his lawsuits aren't doing any good."

Oversight parameters

At issue are the parameters of Congress' constitutionally derived duty to oversee the executive branch, which allows the American people to hold the government accountable through their elected representatives and is seen as a critical element of the "checks and balances" embedded within the federal system.

WATCH: Trump, Congress Wage Oversight War

"Without oversight, Congress has no way to check up on the president," Georgetown University law professor Victoria Nourse said. "This governs every president and it makes sure that the people can control a president who is pushing his authority too far, whether they are Democrats or Republicans."

"Congress has to pass laws. In order for it to pass laws, it has to gather information," George Washington University constitutional law professor Alan Morrison said. "Are the laws being properly executed? Do we need new laws? None of those can be determined without getting information."

Congress frequently secures witness testimony and documents voluntarily and without a fight. When lawmakers encounter resistance, they have a powerful tool at their disposal: subpoena power.

"The Congress can subpoena any material that is related to existing legislation, anticipated legislation, or anything that would serve what the Supreme Court called informing [the] function of Congress," Nourse said. "So they [lawmakers] have pretty broad power here."

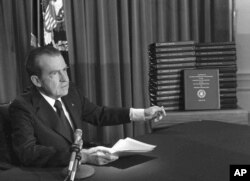

Echoes of Watergate

Legislative subpoena power was famously put to the test in 1974 when then-President Richard Nixon fought against handing over incriminating audiotapes of Oval Office conversations to the Senate committee investigating the Watergate scandal. Nixon's legal team unsuccessfully argued the tapes were privileged executive branch material.

"Nixon sought executive privilege to deny Congress the tapes. And the Supreme Court said, 'No, you have no absolute privilege. You have a qualified privilege and that privilege can be outweighed by the need for the information.' So Nixon lost that case, the tapes were delivered [to Congress], and we all know what happened," Nourse said.

Nixon resigned weeks after the Supreme Court's unanimous decision.

Subpoena court battles

Many are predicting court battles over House subpoenas issued to the Trump administration.

"My assumption is all of these issues are going to end up in the courts," Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell, a Kentucky Republican, said. "Every administration since I've been around has been in disputes with Congress over power … and we'll see how it all sorts out."

In the case of Trump's tax returns, courts will have competing interests and precedents to consider, according to legal scholars.

"As I read the statute, it is within Congress's authority to seek the tax returns," Nourse said.

"Congress can ask to see anyone's tax returns, and that includes obviously corporations as well as individuals," Morrison said. "But this time, they're asking not only for the tax returns when the person is the president, but they want President Trump's tax returns back for six or seven years [before he entered office]. And that raises a different set of issues."

While holding off on impeachment proceedings against Trump over the results of the Russia investigation, top House Democrats warned the president could trigger impeachment by failing to comply with congressional subpoenas.

Whether hindering congressional oversight is an impeachable offense depends on Trump's behavior going forward, according to Morrison.

"Being recalcitrant? Probably not [impeachable]. Refusing to honor court orders? Definitely," the professor said.