The U.S. will withdraw from the Paris climate deal, President Donald Trump announced Thursday, fulfilling a key campaign promise but putting at risk global efforts to deal with the effects of climate change.

At a ceremony in a sweltering White House Rose Garden Thursday, Trump said the accord did little to help the environment and unfairly punished the U.S. by holding it to tougher standards than other top polluters.

“The Paris Climate Accord is simply the latest example of Washington entering into an agreement that disadvantages the United States to the exclusive benefit of other countries,” Trump said.

The move comes despite passionate protests from world leaders and entrepreneurs, many of whom personally pleaded with the president in recent days to stay in the climate deal.

In the end, Trump rejected the accord as an attempt by “foreign lobbyists” who want the U.S. “tied up and bound down” so that their countries can have the “economic edge.”

“I was elected to represent the citizens of Pittsburgh, not Paris,” Trump said.

Renegotiate?

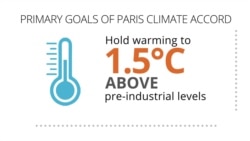

The deal, reached in 2015, set goals for reducing greenhouse gas emissions and limiting the rise in global temperatures. It was signed by 195 countries.

Trump said he would like to immediately begin talks to either re-enter the accord or “an entirely new transaction on terms that are fair to the United States.”

“We will see if we can make a deal that’s fair,” Trump said. “And if we can, that’s great. And if we can’t, that’s fine.”

The withdrawal represents perhaps the most significant rollback yet of the foreign policy legacy of Trump’s predecessor, President Barack Obama.

In a statement, Obama suggested Trump’s decision amounts to an “absence of American leadership” but said U.S. businesses would nonetheless “step up and do even more to lead the way” on climate issues.

During the presidential campaign, Trump repeatedly vowed to tear up the agreement, which he said was hurting American workers.

A global-warming skeptic

Though much of Trump’s opposition to the deal appears to stem from economic concerns, there is also a question whether Trump believes in the problem that the accord was meant to address in the first place - global warming caused by unbridled industrial development .

On various occasions, Trump has suggested that he does not believe in global warming at all. In a 2012 tweet, Trump famously said he believes the concept was a hoax created by the Chinese in order to hurt the U.S. economy.

At a briefing Thursday, a senior White House official declined to say whether Trump believes that human activity contributes to global warming.

“That’s not the point,” the senior administration official said. When pushed, he told reporters to “stay on topic, please.”

The official also declined to say how Trump plans to renegotiate the deal, but insisted his desire to enter the new talks was “very sincere.”

Many world leaders do not share that desire. In a joint statement, the leaders of France, Germany, and Italy said they “firmly believe” the Paris agreement cannot be renegotiated.

Impact of withdrawal

Pulling away from the deal will have far-reaching global impact, as the U.S. is the world’s biggest economy and second-biggest polluter.

However, the immediate environmental consequences of the decisions are unclear.

The White House had already announced it would not follow through on many of the key climate change targets set by Obama.

And many U.S. businesses are likely to continue their trend toward cleaner policies, says Andrew Light, senior climate adviser to Obama’s State Department.

“Climatically, there won’t be a huge difference unless other countries start leaving Paris because the U.S. left Paris,” Light told VOA.

For now, there are few signs other countries will follow Trump’s lead. Many of the world’s biggest polluters, including China, the European Union and India have already vowed to keep their commitments outlined in the deal.

Perhaps more significant is the geopolitical impact of Trump’s decision, according to many of Trump’s critics, who see the move as evidence Trump is abdicating Washington’s traditional role as global leader.

Nina Hachigian, U.S. ambassador to the Association of Southeast Asian Nations under Obama, called the decision an “utter disaster.”

“One hundred ninety-five countries have signed that. If we want to be a global leader, we can't pull away from an agreement that has that kind of unanimity - just on foreign policy alone, let alone the future of the planet,” she says.

Global leaders already had good reason to question U.S. commitment to international climate deals. In 2001, then-President George W. Bush pulled the U.S. out of the Kyoto Protocol, which also aimed to limit greenhouse gas emissions.

Then, as now, there was widespread conservative opposition to the U.S. entering such a climate pact. And in both cases, conservatives welcomed the decision to withdraw.

“This agreement was never ratified by the Senate, nor would it be,” says Jonathan Adler, a law professor at Case Western Reserve University. “It’s high time policy makers moved beyond the fantasy that symbolic international agreements of this sort are a useful way to address our environmental challenges.”

VOA White House correspondents Peter Heinlein and Steve Herman contributed to this report.