The Trump administration says Texas has scrubbed its voter ID law of any potential discrimination and wants a judge who once compared the measure to a “poll tax” on minorities and the poor to resist further action.

That stance from the U.S. Justice Department, filed in court Wednesday, continues a reversal from Washington over what critics call one of the most restrictive voter ID laws in the nation. Under former President Barack Obama, the federal government joined minority rights groups in suing Texas over measure passed by the Republican-controlled Legislature in 2011.

But that position has changed with President Donald Trump in charge, who has established a commission to investigate allegations of voter fraud in the 2016 elections. Trump last week tweeted frustration over the fact that all states are not fully cooperating with requests for details about every voter in the U.S., and even Texas has said it will only turn over information that is already public.

In February, the Justice Department abandoned the argument Texas passed voter ID rules with purposeful discrimination in mind. Now it says Texas lawmakers fixed things in May by ratifying a weaker version that should satisfy the courts.

The decision rests in the hands of U.S. District Judge Nelva Gonzales Ramos of Corpus Christi, Texas, who has twice ruled that original law was intentionally meant to suppress minority voters.

“Texas’s voter ID law both guarantees to Texas voters the opportunity to cast an in-person ballot and protects the integrity of Texas’s elections,” the Justice Department wrote.

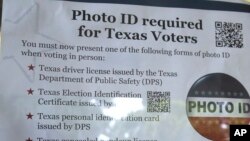

Under the original Texas law, voters had to present one of seven acceptable forms of ID to cast a ballot — concealed handgun licenses were OK, but not college student IDs. The new version allows people without one of those IDs to cast a ballot if they sign an affidavit and bring paperwork showing name and address, such as a bank statement or utility bill.

Democrats and minority rights group contend the weakened version remains too restrictive and could have a chilling effect on voters because it makes lying on the affidavit a felony. In May, Republican lawmakers said the state wouldn’t go after voters who make an honest mistake on the form, while also defending the original law as a necessary safeguard.

Opponents ultimately want courts to put Texas elections back under federal supervision, which would require the state to seek permission to change voting laws.