The Ralbovskys' spare bedroom in a leafy Washington suburb is empty.

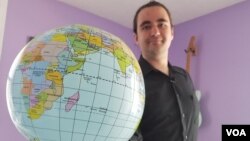

Sure, there is the white day bed pushed against the bright purple walls below a map of Syracuse, New York, where the couple met, a computer on a corner desk beside an inflatable globe, a picture-dictionary binder on a nearby bookshelf.

But the arrival of the couple's foster son - a 17-year-old boy living in an Ethiopian refugee camp - is weeks overdue.

"There's a physical hole in our house, where there's a completely empty room," Carissa Ralbovsky says. "It's just this hole that's shaped like this kid, and nothing else can fit it."

Foster families across the United States await dozens of refugee children like this one who are under 18, and who by definition have no close family to care for them.

For weeks, there has been doubt over whether the children would be blocked from travel under recent U.S. guidelines that require a "bona fide" close family connection or relationship with an "entity" for admittance to the country.

Late Thursday, a judge in Hawaii ruled that the resettlement agencies that serve newly-arrived refugees count as a "formal" and "documented" relationship with an entity, in a move that could allow these children to be united with their foster families.

A spokesperson for Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area, which manages the Carissa and Joe Ralbovsky's case, said the agency is "hopeful that last night's court ruling regarding the definition of 'bona fide relationships' will reopen the door for the refugee youth..."

But the agency has not yet received word from the U.S. State Department about how refugee officials will interpret the ruling.

WATCH: Travel Ban Complicates Wait for Refugee Foster Children

"We are reviewing the decision and will be in consultation with the Department of Justice to ensure immediate implementation," a State Department spokesperson told VOA early Friday.

Lutheran Immigration and Refugee Services (LIRS), one of two non-profit refugee agencies that serves the country's Unaccompanied Refugee Minors (URM) program, says it has a list of 39 children who have already been matched with families and only need to be approved for travel by U.S. officials, including the Ralbovskys' foster son

Kay Bellor, a vice president at LIRS, said the agency has asked the government for a blanket waiver to exempt all URMs from the "bona fide" relationship standard. If that fails, they will try to obtain humanitarian waivers on an individual basis.

"We are prepared to file one individually for every child we've got," says Bellor.

Under the guidelines prompted by the U.S. Supreme Court and explained by federal officials late last month, foster parents are not mentioned under the list of "bona fide" relationships that the government says constitute a close relative in the U.S.

LIRS and Lutheran Social Services of the National Capital Area said earlier this week that they had not received clear indication from federal officials of if or when the refugee children will be able to travel. The State Department and the Office of Refugee Resettlement did not answer VOA's questions about the future of the URM program under the guidelines issued in late June.

Does she like kittens?

Two guest rooms in Irene Stevenson's Washington, D.C., home are furnished and sparsely decorated. As she went through the training and certification to become a refugee foster parent, she thought maybe a pair of siblings would need a home, and she had the extra space.

She was instead matched with one teenager, an ethnic minority who fled Somalia to Kenya. If the teen does arrive, she will be welcomed at the rowhouse along a wide avenue by two lumbering Russian wolfhounds, a poofball of a gray cat, and a woman who has prepared her family and friends to be the girl's support system.

Stevenson has known the name and a bit of her foster daughter's background for a few months, but like other refugee foster parents, she's never seen a photo, or talked with her. She put blinds up in the girl's bedroom, but there are no curtains yet - she's waiting to learn what the teen likes.

"I don't know her favorite color. I don't know if she likes kittens. I don't know any of these things that you know about your child," says Stevenson."But what I do know is that this is a girl that needs me. And so I think about her. I pray for her. I hope that she's going to come here."

Stevenson and the Ralbovskys began the process to become foster parents before the November 2016 presidential election, and the inauguration of a president focused on slashing the country's refugee program to ensure national security.

"As the rhetoric of the 2016 campaign was going on, it was obvious that refugees and Muslims were being targeted as ‘other'," says Stevenson.

Two federal appeals courts agreed, upholding lower courts' decisions to block the Trump administration's travel ban on six countries and all refugees. The Supreme Court will hear the cases in the fall.

So the aspiring parents continued the process, attending parenting classes, providing fingerprints and information for background checks, opening their doors to home inspections and interviewers late into the evening, and learning CPR. They turned down jobs outside of the D.C. area, planned vacation time to spend with the kids over the summer, and invited family for the scheduled arrival dates.

'Trying to be a parent'

In late June, the U.S. Supreme Court allowed exceptions to the travel ban for refugees and citizens of the six countries, if the travelers could prove a "bona fide" relationship with close relatives or an entity in the U.S.

"Fostering is a little bit outside that relationship - there is no blood, but there is a full responsibility relationship," Stevenson explained. "They have no one in the world, there's no one lobbying on their behalf."

The foster parents don't know what the teens know - would it help them to hear that they have bedrooms ready and foster grandparents desperate to meet them? Parents who planned adventures around teaching them to use the subway? A bike waiting in a backyard? Maybe it's better if they don't know, the parents wonder, so they aren't disappointed again.

On a Tuesday morning in July, when Joe Ralbovsky has stepped out of the house, his cell phone rings with a Washington number. Carissa hesitates, but answers - because it could be a response to any of the dozens of calls and inquiries they've made to government officials and members of Congress about how to get their foster son to the U.S.

Instead, it's someone from the English language classes they had already enrolled the boy in, since they expected him in late June, hoping to give him a head start ahead of high school in the fall. Maybe he'll be here in time for a session later in the summer, she wonders out loud.

"Even though there's a small chance - a very small chance - that our kid and the others that are in his situation will get the help that they need, that's enough of a chance for us to keep trying until there's absolutely no opportunity left," says Joe Ralbovsky. "We're not trying to be friends or sponsors or patrons of these people who need help… What we're trying to be is a parent. We're trying to be the guardians of this kid. We wouldn't be doing our jobs if we gave up before it was too late."