Since the last Summer Olympics in 2016, a global Black Lives Matter protest movement has resurfaced. The “Me Too” movement sprung up in support of women’s rights. And both may influence the Tokyo Games, which are expected to be a major platform for athlete activism.

Several high-profile athletes competing at the Games have been at the forefront of progressive causes in their own countries and may make political statements in Tokyo, despite the International Olympic Committee threatening to punish those who speak out.

“The more there are vibrant social movements in the streets, the better chances that we will see activism on the Olympic stage,” said Jules Boykoff, a former Olympic soccer player and author of four books on the Olympics. “I think we have a perfect storm, if you will, for an outburst of athlete activism.”

Political protests are technically banned at the Games by Olympic Charter Rule 50. Though the rule was loosened earlier this year to allow more athlete expression, it still forbids protests from the medal stand or field of play.

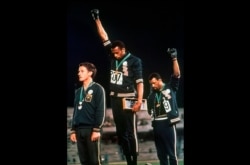

Rule 50 was enacted after the 1968 Olympics produced one of the most inspiring athlete protests in Olympic history. That’s when U.S. stars Tommie Smith and John Carlos raised their fists into the sky on the medal stand in a Black Power Salute.

Contradictions

Smith and Carlos are now widely viewed as icons for their salute. Even the IOC website praises the men as “legends,” calling their move a “gesture of true rebellion.”

“They wanted to make a statement, and they did, on the biggest stage,” says a video on the IOC’s official Olympic Channel.

That stands in contrast to the recent comments by IOC chief Thomas Bach, who recently warned against what he called divisive protests at the Tokyo Games.

“The podium and the medal ceremonies are not made ... for a political or other demonstration,” Bach told the Financial Times. “They are made to honour the athletes and the medal winners for sporting achievement and not for their private [views].”

It’s an apparent case of the IOC wanting to have it both ways, because under the current rules, the 1968 protest would be forbidden, Boykoff said.

“These guidelines do not permit there to be a new John Carlos and Tommie Smith at the Tokyo Olympics,” he said. “They could face punishment.”

The newly relaxed Rule 50 is vague about punishment. It’s not clear to what extent it will be enforced.

Separately, the U.S. Olympic and Paralympic Committee announced late last year it would no longer punish U.S. athletes who conduct peaceful protests, such as kneeling or raising a fist.

Protests already starting

On Wednesday, the first day of competition in Tokyo, players from at least four women’s soccer teams - the United States, Sweden, Chile and Britain - knelt before play.

Others are expected to follow.

Professional U.S. athletes — most prominently basketball players but also others — have attended anti-racism protests and worn Black Lives Matter gear before and during games.

U.S. soccer star Megan Rapinoe has also been outspoken for equal pay for women.

The British women’s football team has already announced it will take a knee before its matches to protest racism and discrimination.

Conservatives, including most notably former U.S. President Donald Trump, often criticize activist athletes, saying players should stick to sports. But even Trump has embraced players who support him and who defend conservative ideals.

Intertwined with politics

“In reality, there has never been a separation of sport and politics,” said Heather Dichter, a professor of sports history at Britain’s De Montfort University.

That’s especially the case with the Olympics, which is full of national flags, symbols, and anthems, Dichter said.

“This is the world’s biggest platform,” she added.

But not every athlete will feel comfortable speaking out. Wealthier players who receive large salaries from their professional careers may be more likely to risk punishment by speaking their minds.

“If you’re an athlete from a lesser-known sport who might get kicked off the team and have their career ended by standing up for politics and lose all your sponsorships, which are the only thing that can keep you going as an athlete, you might be less inclined to speak out,” Boykoff said.

Since there is an abundance of professional athletes competing in the Games this year, it’s just more reason to expect protests.

“It actually opens the door to the possibility that these athletes might speak out,” he said. “After all, the Olympics need these athletes more than these athletes need the Olympics.”

VOA’s Jesusemen Oni contributed to this report.