Angola has blamed a separatist group in its volatile enclave of Cabinda for Friday’s attack against Togo’s national football team. Prime Minister Paulo Kassoma called last week’s ambush of Togo’s African Cup of Nations team bus by a faction of FLEC – the Front of the Liberation of the Enclave of Cabinda – “an isolated act.”

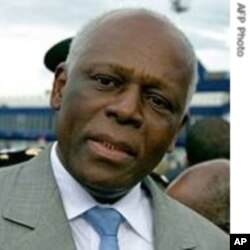

President Jose Eduardo dos Santos has vowed that the games will continue despite the cancellation of Monday’s Nations Cup match between Ghana and the impaired Togolese club. The team flew home to Lome on Sunday after gunmen killed their assistant coach, a club spokesman, and their bus driver. Eight others suffered injuries in the Cabinda raid.

Researcher Lisa Rimli recently returned from Cabinda after monitoring conditions there in November for Human Rights Watch. She says the region has remained tense after a shaky 2006 peace agreement, and last week’s attack was not an isolated incident.

“It’s a tragic event that took place in Cabinda, but surely, it was not an isolated incident, and we just need to see what will happen after that -- what will be the response -- and hoping that the international public will not drop all the attention that they give to this particular region, once the sport event is over,” she said.

The oil-rich enclave, located on a narrow strip which lies between the Republic of Congo (Brazzaville) and the Democratic Republic of Congo (Kinshasa), is separated physically from the rest of Angola, but bonded economically and politically through a four-year-old peace agreement. The treaty, negotiated by the Luanda government and one FLEC faction, has been rejected by other separatist guerilla factions which have claimed the right to launch raids to disrupt Angola’s hosting of the Nations Cup.

“The Angolan government has been able to play all of these factions against each other with some success,” says Rimli. “At this moment, it’s not really clear who perpetrated the attack. There is a faction that doesn’t seem to have acted at the order of the FLEC-FAC (armed forces) leadership in Paris, so it’s not really clear what is happening within the guerrillas and who is in control of what.”

The widespread popularity of international football has deepened the impact of the rebel attack, not only because it endangered the lives of Togo’s players, several of whom earn their principal livelihoods by competing internationally in Europe, but also since it raises security questions for fans who attend the competition.

Several African heads of state showed up in Angola’s capital, Luanda, for the tournament, including Zambia’s President Rupiah Banda and South Africa's Jacob Zuma, whose country will host the World Cup in June of this year.

While Togo’s government blames Angola for failing to warn club officials about inadequate security in Cabinda, where Monday’s match had been scheduled to be played, Angola says Togo violated Confederation of African Football (CAF) rules requiring all teams to avoid land transportation and travel to the tournament by plane. Human Rights Watch researcher Rimli says that despite wide-ranging accounts taking credit for the attack, it’s not clear who was being targeted.

“Certainly it was a bad idea to travel by road. But I don’t know who took this decision. What is clear is that the Angolan government has sent protection units, actually from the rapid intervention police, which are heavily armed, and they were actually escorting the buses. So they were not completely alone. That’s why also the guerillas claim that they actually targeted the rapid intervention police or the security forces. But that’s another thing,” Rimli points out.