Tippi Hedren is an American actress. But acting wasn’t her first line of work. Hedren started out as a successful fashion model who appeared in magazines while in her 20s. In 1961, her appearance in a television commercial caught the eye of British film director and producer, Alfred Hitchcock.

“I was having a wonderful time doing television commercials, Hedren says. “I never ever dreamed that I would become an actress. Never. I didn’t see myself as an actress. It just happened,” she says.

Hedren is best known for her role in Alfred Hitchcock’s 1963 thriller “The Birds,” and the psychological drama “Marnie.”

Hedren says she loves animals and exotic cats. In 1969, while shooting two films in Africa, she learned about Africa’s lions.

“I had the opportunity to go out and see the animals running free, and to kind of watch them and get to know a little about their life and the dangers that they have,” Hedren says.

Later, Hedren says she was dismayed to find out how many lions and tigers were being bred in the United States to be sold as a pets, and that there were no laws in the U.S. that prohibited the breeding of these animals.

To raise awareness for lions, Hedren and her husband Noel Marshall produced and starred in the film “Roar” in 1981.

The film was a turning point in Hedren’s life, where she became an animal rights activist. Hedren was instrumental in getting a law passed banning the breeding of exotic cats as pets or for personal ownership in the United States.

“The bill passed unanimously in the House and Senate. And President Bush signed it,” she says.

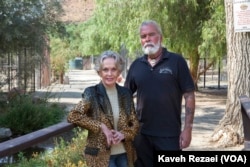

In 1983, Hedren founded the Roar Foundation. It exists to support the Shambala Preserve, a sanctuary for exotic felines that cannot be returned to the wild. Hedren runs Shambala with longtime associate Chris Gallucci.

Tippi Hedren also has devoted much time and effort to a wide variety of humanitarian and environmental causes. During the Vietnam War, Hedren volunteered as a relief coordinator for charity organization “Food for the Hungry.” She has traveled worldwide to set up relief programs following earthquakes, hurricanes, famine and war, and has received numerous awards for her efforts.

Hedren also sparked the beginning of the Vietnamese nail salon industry. While helping at a refugee camp in California, Hedren noticed the Vietnamese women admiring her nails.

"They loved my fingernails. They were fascinated with my fingernails," said Hedren.

Thinking of how to help the new immigrants get a job, Hedren invited her manicurist to teach a class of about 20 women at the refugee camp how to paint nails and perform techniques such as the Juliette wrap.

“It became an amazing thing because these women are great networkers.” “It just went all over the United States,” Hedren says.

In 2015, 80 percent of nail technicians in California, and 51 percent of all nail technicians in the United States, were of Vietnamese descent.

“I am the Godmother for the manicurist of the Vietnamese woman,” she says. “I’m very proud of that and I am proud to say that I have never made a dime on it, it is my gift to them.”