“That insect’s dead.”

Shawn Semones holds up a little plastic cup in which a little worm-like insect lies in repose, sprouting a fine white coat of mold.

That fungus not only killed the insect pest, the white coat is producing spores that will blow in the wind to infect another insect.

“This is a naturally occurring microorganism,” said Semones, head of agricultural research and development at the biosciences company Novozymes. “We’ve just come up with a way to produce it at an industrial scale, stabilize it and offer it to farmers as a biopesticide.”

Next big thing

Welcome to the next big thing in agriculture. It’s small. Microscopic, in fact.

Novozymes recently signed a $300 million deal with the seed and chemical giant Monsanto to help bring new discoveries in the microbial world to farmers’ fields.

It's just one indication of the promise that scientists see for these tiny microbes to help farmers produce more with less.

The world population is expected to climb to nine billion by 2050, from seven billion today. And people are getting richer and demanding better food. So agriculture will need to produce about 70 percent more by mid-century, experts say, and do so in a changing climate, with threats to land, water and fertilizer resources, and while causing less harm to the environment.

Answers in soil

Researchers are finding answers to that challenge in soil beneath our feet.

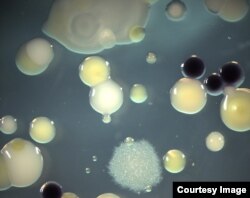

“Soil is teeming with life,” said University of North Carolina biology professor Jeff Dangl. A gram of soil contains anywhere from a hundred million to a billion microbes.

That megalopolis of microbes is engaged in a thriving barter economy with the plants that share the soil.

Plants make sugar through photosynthesis.

“Much of that sugar is actually pumped down through the roots,” Dangl said, where it is turned into sugar-based microbe food and secreted into the soil. “They do that specifically to recruit microbes to help the plants grow better.”

Some of those recruits turn chemicals in the air and soil into food the plants can eat. Novozymes already sells one type of fungus that helps plants get phosphorous from the soil.

Other microbes act as bodyguards, producing antibiotics and other chemicals to fight off the bad germs.

Bacterial and fungal friends

“What’s really blown this field open,” Dangl added, “is the realization that, if we want to understand the way the plant organism functions, we have to consider its bacterial and fungal friends part of that organism.”

The same realization is taking place in human medicine. Scientists are discovering that the microbes living on and in every one of us -- whose cells outnumber our own 10 to 1 -- are much more important than we have given them credit for. More than merely helping us digest our food, a growing body of research shows this biome is involved in everything from allergies to obesity to regulating moods.

These discoveries owe a lot to advances in DNA sequencing. The technology first used to decode humans’ entire genetic blueprint has come so far in just the last few years, Dangl says, that “we now can, for $50, sequence the complete genome of essentially any bacteria on earth.”

“Our technical abilities have gone through the roof in terms of understanding what’s in a gram of soil,” said Purdue University soil scientist Ron Turco.

For example, soil from one particular field may prevent peas from getting a wilting disease.

“There’s something in that soil," Turco said. "You take your genetic tools and you look for things that are different, and you can bring out the organisms that are doing that job.”

But it’s not easy, he added. “You can show an effect in soil but sometimes you can never really isolate that bacteria out. It’s a whole art form to recover a microorganism from soil. And that’s not insignificant.”

And a microbe that works in one place will not necessarily work in another.

Researchers in the northwestern United States have found bacteria that fight a fungus which rots the roots of wheat plants. But, UNC’s Jeff Dangl notes, they don’t seem to work anywhere else.

Dangl co-founded a North Carolina startup company, AgBiome, which is working on this problem.

One of their most promising leads is a bacterium that fights off a fungal disease common in greenhouses. In the lab, it produces “the kind of control you would usually achieve with a commercial fungicide chemical,” said AgBiome’s chief science officer, Dan Tomso.

Dangl hopes to develop a seed treatment that combines several disease-fighting and fertilizing microbes into a probiotic mix that works in a variety of soils.

Purdue’s Ron Turco sees the new interest in the soil as good news for an under-studied field.

“Soils are our major resource in this country that allows us to get away with all the things we’re able to get away with in terms of food production,” he said. “We’ve got tremendous soil resources that we don’t completely understand.”

Shawn Semones holds up a little plastic cup in which a little worm-like insect lies in repose, sprouting a fine white coat of mold.

That fungus not only killed the insect pest, the white coat is producing spores that will blow in the wind to infect another insect.

“This is a naturally occurring microorganism,” said Semones, head of agricultural research and development at the biosciences company Novozymes. “We’ve just come up with a way to produce it at an industrial scale, stabilize it and offer it to farmers as a biopesticide.”

Next big thing

Welcome to the next big thing in agriculture. It’s small. Microscopic, in fact.

Novozymes recently signed a $300 million deal with the seed and chemical giant Monsanto to help bring new discoveries in the microbial world to farmers’ fields.

It's just one indication of the promise that scientists see for these tiny microbes to help farmers produce more with less.

The world population is expected to climb to nine billion by 2050, from seven billion today. And people are getting richer and demanding better food. So agriculture will need to produce about 70 percent more by mid-century, experts say, and do so in a changing climate, with threats to land, water and fertilizer resources, and while causing less harm to the environment.

Answers in soil

Researchers are finding answers to that challenge in soil beneath our feet.

“Soil is teeming with life,” said University of North Carolina biology professor Jeff Dangl. A gram of soil contains anywhere from a hundred million to a billion microbes.

That megalopolis of microbes is engaged in a thriving barter economy with the plants that share the soil.

Plants make sugar through photosynthesis.

“Much of that sugar is actually pumped down through the roots,” Dangl said, where it is turned into sugar-based microbe food and secreted into the soil. “They do that specifically to recruit microbes to help the plants grow better.”

Some of those recruits turn chemicals in the air and soil into food the plants can eat. Novozymes already sells one type of fungus that helps plants get phosphorous from the soil.

Other microbes act as bodyguards, producing antibiotics and other chemicals to fight off the bad germs.

Bacterial and fungal friends

“What’s really blown this field open,” Dangl added, “is the realization that, if we want to understand the way the plant organism functions, we have to consider its bacterial and fungal friends part of that organism.”

The same realization is taking place in human medicine. Scientists are discovering that the microbes living on and in every one of us -- whose cells outnumber our own 10 to 1 -- are much more important than we have given them credit for. More than merely helping us digest our food, a growing body of research shows this biome is involved in everything from allergies to obesity to regulating moods.

These discoveries owe a lot to advances in DNA sequencing. The technology first used to decode humans’ entire genetic blueprint has come so far in just the last few years, Dangl says, that “we now can, for $50, sequence the complete genome of essentially any bacteria on earth.”

“Our technical abilities have gone through the roof in terms of understanding what’s in a gram of soil,” said Purdue University soil scientist Ron Turco.

For example, soil from one particular field may prevent peas from getting a wilting disease.

“There’s something in that soil," Turco said. "You take your genetic tools and you look for things that are different, and you can bring out the organisms that are doing that job.”

But it’s not easy, he added. “You can show an effect in soil but sometimes you can never really isolate that bacteria out. It’s a whole art form to recover a microorganism from soil. And that’s not insignificant.”

And a microbe that works in one place will not necessarily work in another.

Researchers in the northwestern United States have found bacteria that fight a fungus which rots the roots of wheat plants. But, UNC’s Jeff Dangl notes, they don’t seem to work anywhere else.

Dangl co-founded a North Carolina startup company, AgBiome, which is working on this problem.

One of their most promising leads is a bacterium that fights off a fungal disease common in greenhouses. In the lab, it produces “the kind of control you would usually achieve with a commercial fungicide chemical,” said AgBiome’s chief science officer, Dan Tomso.

Dangl hopes to develop a seed treatment that combines several disease-fighting and fertilizing microbes into a probiotic mix that works in a variety of soils.

Purdue’s Ron Turco sees the new interest in the soil as good news for an under-studied field.

“Soils are our major resource in this country that allows us to get away with all the things we’re able to get away with in terms of food production,” he said. “We’ve got tremendous soil resources that we don’t completely understand.”