A cure for the common cold may be just around the corner.

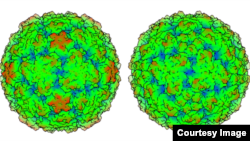

A three-dimensional model of the rhinovirus C, the virus behind up to half of all childhood colds, reveals why effective treatment for the ailment remains elusive and could open the door to a cure.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison created a meticulous topographical model, of the virus, which was only discovered in 2006. The model showed the virus is distinct from other cold viruses.

The various rhinoviruses, A, B and C are responsible for millions of illnesses annually at a cost of $40 billion in the U.S. alone.

The A and B families of cold virus, including their three-dimensional structures, have long been known to science as they can easily be grown and studied in the lab. Rhinovirus C, on the other hand, resists culturing and escaped notice entirely until 2006 when “gene chips” and advanced gene sequencing revealed the virus had long been lurking in human cells alongside the more observable A and B virus strains.

“The question we sought to answer was how is it different and what can we do about it? We found it is indeed quite different,” said biochemistry professor Ann Palmenberg, noting that the new structure “explains most of the previous failures of drug trials against rhinovirus.”

The detailed model could pave a way to cures, researchers said.

Antiviral drugs work by attaching to and modifying surface features of the virus. To be effective, a drug, like the right piece of a jigsaw puzzle, must fit and lock into the virus. The lack of a three-dimensional structure for rhinovirus C meant that the pharmaceutical companies designing cold-thwarting drugs were flying blind.

Because the three cold virus strains all contribute to the common cold, drug candidates failed because the surface features that permit rhinovirus C to dock with host cells and evade the immune system were unknown and different from those of rhinovirus A and B.

Based on the new structure, researchers said a “C-specific” drug would have to be made.

“It has a different receptor and a different receptor-binding platform,” Palmenberg explains. “Because it’s different, we have to go after it in a different way.”

A three-dimensional model of the rhinovirus C, the virus behind up to half of all childhood colds, reveals why effective treatment for the ailment remains elusive and could open the door to a cure.

Researchers at the University of Wisconsin-Madison created a meticulous topographical model, of the virus, which was only discovered in 2006. The model showed the virus is distinct from other cold viruses.

The various rhinoviruses, A, B and C are responsible for millions of illnesses annually at a cost of $40 billion in the U.S. alone.

The A and B families of cold virus, including their three-dimensional structures, have long been known to science as they can easily be grown and studied in the lab. Rhinovirus C, on the other hand, resists culturing and escaped notice entirely until 2006 when “gene chips” and advanced gene sequencing revealed the virus had long been lurking in human cells alongside the more observable A and B virus strains.

“The question we sought to answer was how is it different and what can we do about it? We found it is indeed quite different,” said biochemistry professor Ann Palmenberg, noting that the new structure “explains most of the previous failures of drug trials against rhinovirus.”

The detailed model could pave a way to cures, researchers said.

Antiviral drugs work by attaching to and modifying surface features of the virus. To be effective, a drug, like the right piece of a jigsaw puzzle, must fit and lock into the virus. The lack of a three-dimensional structure for rhinovirus C meant that the pharmaceutical companies designing cold-thwarting drugs were flying blind.

Because the three cold virus strains all contribute to the common cold, drug candidates failed because the surface features that permit rhinovirus C to dock with host cells and evade the immune system were unknown and different from those of rhinovirus A and B.

Based on the new structure, researchers said a “C-specific” drug would have to be made.

“It has a different receptor and a different receptor-binding platform,” Palmenberg explains. “Because it’s different, we have to go after it in a different way.”