There are kernels of good news among the torrent of bad news in the latest climate reports.

Overall, they show the world is still careening toward a world of climate disasters that will be more frequent and more intense than what we're already seeing.

But the speed at which we're heading there has slowed.

For the first time, one major forecast predicts that current policies will bring an end to the relentless growth of fossil fuel use.

The shift to cleaner energy is picking up speed; however, it isn't happening fast enough to keep the global temperature rise below the targets set at a Paris climate conference in 2015.

End of an era

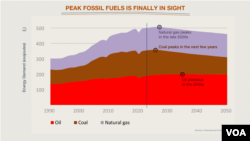

After a nearly unstoppable rise since the beginning of the Industrial Revolution, global fossil fuel use may finally stop growing this decade, according to the latest forecast from the International Energy Agency.

It projects use of coal will start to decline in the next few years, followed by natural gas by the end of the decade. Oil is expected to plateau in the 2030s.

This is the first time the agency predicts that current policies will change the trajectory.

Coal, the most CO2-producing fuel, has gained from the disruption caused by Russia's war in Ukraine this year, but the IEA says it's temporary.

And the growth of renewables and electric vehicles this year helped offset the increase in CO2 emissions from coal. It predicts the current energy crisis will speed, not slow, the transition away from fossil fuels.

A race against time

The report, however, notes that the current pace of decline is not fast enough to avoid unprecedented heat waves, droughts, storms, floods, species extinctions and ecosystem collapses.

World leaders pledged in Paris to limit global warming by the end of the century to "well below" 2 degrees Celsius and to aim for 1.5C. Scientists say the damage from climate change grows considerably between 1.5C and 2C.

The world has seen about 1.1C of warming so far, and the consequences are already being seen in the form of more intense heat waves, droughts, storms and rising seas.

Scientists say emissions need to come down by about 45% by 2030 in order to be on track for 1.5C of warming this century.

Under policies currently in place, the planet is on track for 2.8C of warming, according to the latest Emissions Gap Report from the U.N. Environment Program.

National plans submitted ahead of the next climate summit in November 6-18 in Sharm el-Sheikh, Egypt, would lower that warming only slightly, to 2.6C.

Many of those national plans include additional pledges that require outside financing or other conditions. If all of those pledges are met, that brings warming down to 2.4C.

Eighty-eight countries have pledged to zero out their emissions by 2050. If they manage to do so, that would keep the temperature rise to 1.8C.

The report says that scenario is "not credible" since many of those pledges don't include short-term targets or explain how they would get there.

The good news is, the world has made progress. The forecast going into the Paris climate summit was for around 3.5C of warming.

Countries have committed to go much further and have the tools to do so, the IEA report adds.

Watching out for methane

There's one more concerning bit of data, though.

In addition to record amounts of CO2 in the atmosphere last year, the World Meteorological Organization saw a record jump in levels of another potent greenhouse gas: methane.

Methane is the second-largest contributor to climate change. There is much less methane in the atmosphere than CO2, but it is about 30 times more powerful.

It is the main component of natural gas, which has become an increasingly important fuel for electric power plants and industrial uses. Leaks along the supply chain are contributing to the rise in atmospheric methane.

These are not the only sources. And they may not be the biggest contributors to the sharp increase.

Methane is a by-product of decay. Microbes starved of air produce it as they break down dead plants and animals.

Scientists are not sure, but it appears that methane emissions from tropical wetlands are the biggest factor in the rising levels in recent years.

Since microbes work faster in warmer temperatures, a warming planet may mean they produce even more methane in years to come.

More methane means more warming. More warming means more methane.

It's one of the dangerous feedback loops that scientists say may accelerate climate change, which makes cutting human emissions all the more urgent.