“When they go low, we go high,” former first lady Michelle Obama recited as her motto.

When it comes to electability, however, that could be bad advice — but not in the way that might be imagined.

Research into the voices of political candidates concludes how a contender speaks is critical — and lower pitch is better.

“Individuals with lower voices are more likely to win and to win a larger vote share,” says University of Miami Associate Professor Casey Klofstad. “What our experimental data show is that we like candidates with lower voices, largely because they are perceived as stronger and more confident and, to a lesser degree, because they're perceived as older.”

This tonal bias may partly explain the under-representation of women in elected office. And with a record number of women vying for the Democratic Party’s nomination for U.S. president, the research is receiving wider scrutiny.

Stanford Gregory, emeritus professor of sociology at Kent State University, studied the voice characteristics of the U.S. presidential general election contenders between 1960 and 2000, as well as analyzing the three debates in 2008 between Democrat Barack Obama and Republican John McCain.

Gregory noted a tendency for McCain to show dominance in the lower nonverbal frequencies of his voice while Obama finished the debates more strongly.

Gregory and his Kent State colleague Will Kalhoff observed a "recency effect," in which potential voters take away more of an impression from the end of debates.

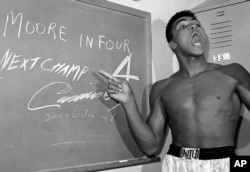

Obama had a "rope-a-dope" debating style akin to the boxing techniques of heavyweight legend Muhammed Ali who would hang back from the start of a fight until his opponent exhausted himself and then dominate the end of the match, according to Gregory who concluded the victorious candidate is the one who sets the tone, so to speak.

“We found it was the person who changed the least in his lower frequencies compared to the other person, so in effect from the beginning, he would set the lower frequency tone and the other person would adapt to that in the course of debates,” says Gregory.

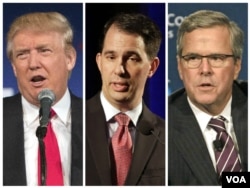

The effect also could be seen in the 2016 Republican primary where President Donald Trump, initially regarded as a longshot, overwhelmed as many as 10 candidates on the debate stage, including former Florida governor Jeb Bush and Senators Marco Rubio of Florida and Ted Cruz of Texas.

“It was just obvious this is what he did,” states Gregory.

As Vox news editor Libby Nelson, also an adjunct professor of public affairs at American University, wrote, looking back on Trump’s primary debates’ performance: Trump would “pick out one or two antagonists during any given debate — always some combination of Bush, Marco Rubio, and Ted Cruz — to try to take down. The point wasn’t to get them to concede a policy point to him, but to establish that Trump was the one who should be allowed to talk.”

Some who work on campaigns cast doubt, however, on relying on such research to predict outcomes of races, especially for presidential contests where voters are more likely to more intensively scrutinize candidates.

“I'm skeptical as a practitioner of anytime someone comes and says, ‘We have isolated the thing that impacts the results of a campaign’— whether it's yard signs, TV ads, money in politics or how someone talks,” says Matt Dole, who has worked on about 250 local and state campaigns of Republican candidates in Ohio.

Dole tells VOA that voices “could have a role” in influencing voters, as might a candidate’s gender, facial characteristics, height, attire and other cosmetic features.

Gregory was asked who among the large field of 2020 Democratic hopefuls might best set the advantageous low tone during the party’s upcoming televised debates?

Senator Elizabeth Warren of Massachusetts “is pretty good at this kind of thing,” Gregory replied, noting he is also curious to see how former Texas Congressman Beto O’Rourke performs.

While Warren’s voice may not be as low as some of her primary race male competitors (or that of Trump), Gregory says what is more important is “the ability to maintain a certain tone and keep it and not alter or fade back on it in the course of the debate or the interview.”

Former Pima County, Arizona Democratic Party Chair Don Jorgensen says,“Warren has learned the secret of speaking slower, breaking up her rhythm and finishing on a strong low beat to keep audiences engaged.”

Jorgensen also says Warren “employs her slightly breathless tone to indicate urgency and rather than attempting to shout at crowds she effectively forces them to tune in to her.”

Effective candidates have learned that speeches and debates “are a form of political performance art, where appearance and tone leave a far stronger impression than the message itself,” Jorgensen tells VOA.

Gregory agrees, putting it even more bluntly.

“What you say doesn't make any difference,” says Gregory, noting Trump’s 2016 boast:“I could stand in the middle of 5th Avenue and shoot somebody and I wouldn't lose voters.”

Gregory says that makes people conclude “You could put anyone up there as long as they had the right kind of frequency insignia.”

Klofstad in Miami has a different take on Trump.

“I don't think Trump is a good case study in the pitch of the voice mattering,” he says, arguing that when it comes to the current president “it’s more cadence,” pointing to Trump’s ability to hold an audience with extemporaneous remarks at big rallies.

Looking at the current pack of Democrats, Gregory contrasts the telegenic O’Rourke (“credibly audacious and articulate when it comes to issues but he’s kind of all over the place”) to lesser known contender Jay Inslee, governor of the state of Washington who focuses on the environmental issue.

On an acoustical basis, according to Gregory, Inslee also seems to maintain a single authoritative tone, meaning “he has a pretty good chance.”

A cacophony of other candidates is certain to voice skepticism about that.