The risks of dissent in Vladimir Putin's Russia came in full view this week, as two separate cases highlighted the country's troubling human rights climate.

On Wednesday, the Russian staff of Amnesty International's Moscow branch arrived to work only to find office locks changed and doors sealed without explanation or warning. According to comments later issued by the Moscow mayor's office, the group had failed to pay rent on time.

“All our computers, papers, personal effects – they’re all still in there, behind the locked doors,” said Amnesty Russia’s Ivan Kondratenko in post published to Facebook.

Noting the group had rented the office from city authorities for 20 years without any incidents or not paying rent on time, Amnesty officials expressed hope the issue would be quickly resolved.

Yet voices from Russia’s human rights community suggested the move was merely a sign of the times.

“The absolute lack of warning serves to reinforce the suspicion that this is not your ordinary landlord/tenant dispute,” says Tanya Lokshina, the director of Human Rights Watch in Russia.

“It’s rather about their Russia work as such, their staunch criticism of the deepening human rights crisis inside Russia,” she tells VOA. “And given the political climate, one has strong grounds to suspect that the action was taken to put pressure on Amnesty International.”

Foreign agents everywhere

Amnesty’s troubles come as human rights groups and other NGOs working in Russia continue to grapple with a spate of recent laws that they say are aimed at stifling their work.

Domestic organizations that once received foreign funding must now register with authorities as “foreign agents” or face crippling fines. Other groups – including U.S. funded institutions like the National Democratic Institute -- have merely been labeled “undesirable” by the authorities and forced to close with little notice.

The government says the moves are designed to prevent outside meddling in Russia’s political system. Human rights groups argue the Kremlin’s larger goal is stifling dissent, no matter how small.

May I protest please

Take the story of Ildar Dadin.

“Ildar was a just a regular guy. He didn’t care at all about politics,” says Dadin’s wife, Anastasiya Zotova. “But in 2012 that all changed,” she tells VOA in an interview.

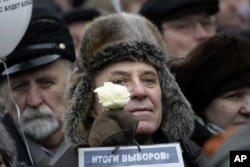

Dadin had volunteered as an election observer amid a contested election season that saw thousands of Russians take to streets to protest what many perceived as widespread vote rigging in favor of Vladimir Putin’s ruling United Russia party.

When Dadin went to authorities with evidence of vote tampering amid the presidential race, he soon found himself detained by the authorities. The experience, says Zotova, turned her husband into a committed activist.

That political awakening brought repeated arrests for lone, peaceful, and – in theory, legal -- protests against the government in the ensuing years.

Tough prison sentence

Yet in December 2015, a Russian court sentenced Dadin to 3 years in prison (later reduced to 2.5 years upon appeal), as a repeat offender of a stricter anti-assembly restriction. Like the ‘foreign agents’ law, the measure had been introduced in the wake of the 2011-2012 protests.

Dadin’s case gained attention again this week after he smuggled out a letter to his wife alleging repeated torture and abuse by authorities at the prison in northwest Russia where he’s currently serving out his sentence.

Allegations of torture

“Over the course of a day, I was beaten a total four times, by 10-12 people at once. They would kick me repeatedly,” he wrote.

Dadin went on to describe being handcuffed and hung from a ceiling as punishment for hunger striking in protest: “Then they took off my underwear and said they would bring another prisoner to rape me unless I stopped….” Prison authorities, he writes, later threatened him with death, adding his was hardly an isolated case.

Russian authorities say they are investigating the claims and since dispatched doctors to verify Dadin’s condition.

But it was Amnesty International Russia -- among a few other independent media and local human rights groups – who helped bring Dadin's letter to the public's attention.

“Ildar Dadin’s allegations of beatings, humiliation and rape threats are shocking, but unfortunately they are just the latest in a string of credible reports indicating that torture and other ill treatment widely used in the Russian penal system with impunity, aimed at silencing any form of dissent” said Sergei Nikitin, the Director of Amnesty International Russia, in a statement issued Tuesday.

The next day, his office locks were changed.