By clinching the Democratic Party's presidential nomination, Hillary Clinton has joined a prestigious club of women who have made history in their search for political power in America.

"The only thread that connects them is their willingness to go against the grain because they did. I mean, the women who have run for president have been quite diverse," said feminist scholar Jo Freeman, author of several books, including "We Will Be Heard:Women's Struggles for Political Power in the United States."

Clinton savored the moment she made history for being the first female to win a presidential nominating contest, saying “We all owe so much to those who came before, and tonight belongs to all of you.”

The first one among those came before was Victoria Woodhull, who in 1872, showed her inner steel when she made her bid for the White House as a candidate of the Equal Rights Party. Her attempt, the first-ever by a female in America, came even before women won the right to vote under the U.S. Constitution in 1920.

Woodhull weathered many attacks for making history, said Erin Blakemore, a freelance journalist who has chronicled and reported on American women in politics for many publications.

"Certainly Clinton has faced charges on par with those lobbed at women like Victoria Woodhull, whose sex life was constantly called out and seen, at the time, as kind of the "price of admission" for her doomed campaign."

After Woodhull, there were a few more attempts, but it wasn't until 1964, Freeman argues, that a breakout female candidate shook up American presidential politics.

"The real icebreaker was Margaret Chase Smith, 1964. She ran for the Republican nomination for president. That was the icebreaker," Freeman said.

"She was a respectable member of the US Senate, she was not a radical," added Freeman, who points out that no women had tried to run for the presidency since the 19th century.

In '64, the Republican ticket belonged to Barry Goldwater.

But Mary Chase Smith was a cause candidate—that is, she knew she wouldn't win against Goldwater. She was practical.

"She ran to raise issues about women, other things she was concerned about, she really had no expectations of getting the nomination, she wanted a platform, she got a platform," Freeman said.

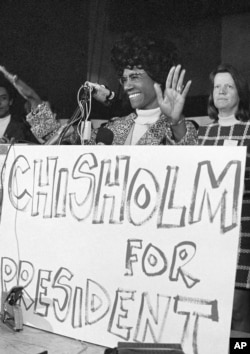

Less than a decade later, another courageous attempt was made. And it was a one-two punch for America in 1972. Shirley Chisholm was not only a woman, but a black one.

"Sometimes I have trouble, myself, believing that I made it this far against the odds," Chisholm said in 1972. She had already made history, being elected the first African-American woman to Congress four years earlier.

The rhetoric aimed at Chisholm was "horrible," said Blakemore, who just wrote a piece about the withering attacks against her in Time.

Blakemore writes:

"One piece by Andrew Tully mourned that “We are, I fear, doomed to an era of female meddling in the electoral process.” Besides, he noted, Chisholm “doesn’t have a chance at top banana, of course.”'

"She actually did better than Mary Chase Smith did, but of course she's running after the women's movement started at a time in which there is both consciousness about women and consciousness about blacks," Freeman said.

"I went to the '72 convention," Freeman added, "By running for president and getting a lot of press about it, placed another big crack in that glass ceiling."

Hillary mentioned that same glass ceiling on last week on Tuesday night, her first as the presumptive Democratic nominee.

"This campaign is about making sure there are no ceilings, no limits on any of us."