In its time, the "stocking frame mechanical knitting machine" was a technological wonder. Introduced into 17th-century England, the bulky and expensive device could generate many times the amount of yarn or textiles that hand-knitters could, and it didn't require skilled workers. Which is exactly why it became the target of such fierce opposition by angry weavers, who in protest would raid a knitting plant and smash the machines.

These roving gangs were known as "Luddites," and although motivated primarily by economic interest, their movement eventually became synonymous with all those opposed to new technology. In the end, the Luddites, like many before them, were unable to stop technology's advance and died out as automation took hold.

However, as the excesses of the Industrial Revolution pointed out, new technologies can bring new troubles, and not all who question their costs can be dismissed as a Luddite.

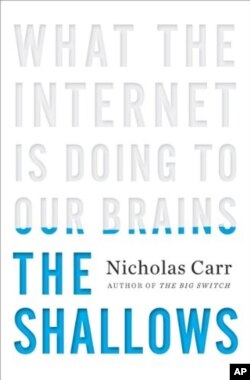

Consider writer and journalist Nicholas Carr. No techno-phobe, Carr has built a career covering the economy, culture and technology in numerous articles and books such as "The Big Switch: Rewiring the World from Edison to Google." Carr's latest book is titled, "The Shallows" and it's raising eyebrows - and in some cases, voices. The reason can be found in the book's sub-heading: "What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains," and from Carr's point of view, the answer isn't reassuring.

"What the 'net does, by being such a distraction machine, is it emphasizes that skimming, rapid fire approach to collecting and processing information," Carr says. "But what it de-emphasizes is all the ways of thinking that require attentiveness, concentration."

As the stocking frame loom was, Carr says, the Internet is like a machine that does one thing very well: it pumps out information in all sorts of forms and in ever-growing volume, encouraging users to skip and skim among it for bits of information. In modern parlance, multi-tasking.

There are two problems with such multi-tasking, says Carr. The first is the quality of work: researchers he quotes suggest the brain is simply not able to handle several different tasks at the same time, so with every flip from task to task, it has to recall the problem, remember where it was, and try to finish the problem. All those flips take time and energy, and may result in poorer overall performance than if each task were finished before moving on.

The second problem is deeper: the quality of thought. "The brain is adaptable...very plastic," Carr says, meaning that it's able to adapt to a wide variety of demands and situations. But the Internet, with all its hyperlinks, widgets and multimedia interruptions, demands people to have shorter and shorter attention spans.

"They tend to reduce our comprehension, reduce our learning, reduce our understanding," says Carr of the multiple tasks familiar to web surfers. And herein lies the problem: if you don't practice longer, more concentrated modes of thought, your ability for deep thought may wane. Carr calls it a "use-it-or-lose-it" kind of problem.

"Those aspects of the brain that we exercise get stronger, they recruit more neurons, literally, into those neural pathways. Those aspects of mind that we neglect get weaker. And so we really do risk losing some mental capacities that are important to our intellectual lives," he notes. Deep reading, creativity and problem-solving all require this focused type of thought, says Carr, adding "...there's not much place on the web for those kinds of habits of mind and as a result I think we're beginning to lose them."

Carr's book is generating a great deal of debate and dissension. Harvard psychology professor Steven Pinker is one of many who argue Carr makes too much of the dangers of multi-tasking, and also overlooks the many benefits the Internet provides, such as cataloging, storing and retrieving almost any bit of information instantaneously.

"Knowledge is increasing exponentially," Pinker wrote recently in the New York Times. "The Internet and information technologies are helping us manage, search, and retrieve our collective intellectual output at different scales, from Twitter and previews to e-books and online encyclopedias. Far from making us stupid, these technologies are the only things that will keep us smart."

Carr agrees that the Internet is an unparalleled achievement in knowledge storage, and also grants that it may be making some parts of our thought processes stronger. "Probably our ability to shift our ... visual focus among lots of different things on a screen, can be improved by our use of the web," he says. "Unfortunately, those gains in visual processing ... come at the expense of some of our deeper modes of thinking; our ability to think in conceptual terms, critical terms, our ability to be reflective. We need to look at both sides of the ledger."

In the end, the Internet is no more likely to be stopped than was the stocking frame knitting machine. And while there's little agreement as to whether the web is eroding our capacity for deep thought, nearly everyone agrees on how to fight it: self-control.

"Turn off e-mail or Twitter when you work, put away your Blackberry at dinner time, ask your spouse to call you to bed at a designated hour," writes Pinker. Carr agrees, but says this is no great surprise. The hard part is actually doing it.

"The expectation of being constantly connected, constantly processing information, is being built very deeply into our work lives, and it's being built into our social lives," he says. "To back away is very hard and requires some sacrifices ... but you really have no choice."

You can follow issues of technology, society and the Internet at our new online site "Digital Frontiers"