"It is like the hydra. You chop off one head, and two pop up."

That’s how one Lakota Indian described the methamphetamine epidemic that is crippling Native American communities across the United States.

Meth was developed early in the 20th century and used to treat hyperactivity, obesity and other disorders. The U.S. declared meth a controlled substance in the 1970s. It wasn’t long before criminal groups began manufacturing the drug illegally, initially in California, but by the 1990s, meth began to spread eastward into rural communities in the West and Midwest.

The drug found its way onto Indian reservations, where today, more Native Americans, proportionately, are addicted to meth than the rest of the U.S. population.

"You’ve got remote areas and less policing. Even the Mexican cartels, as they distribute their meth in the U.S., often they will go to Indian reservations, particularly in Oklahoma, Kansas and on up into the Dakotas, to have the methamphetamine manufactured,” said James E. Copple, founding partner of Strategic Applications International, a group which has contracted with federal government to help Native American tribes fight meth."

"Meth is cheap, easy to use and results in a longer ‘high,’” Copple said. “About 12 hours, compared to heroin, which last only an hour to two."

It’s a highly addictive drug, he said, and over the long-term, leads to paranoia and severe depression.

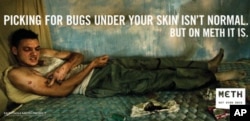

"When they’re high on meth, beyond the paranoia, they have this sense where they feel like their skin is being bitten or eaten by bugs, and so they start slicing away at themselves, picking and scratching away at their skin,” he said. This “pick effect” leads to the open sores and infections associated with meth addicts.

Meth use has led to a rise in violent crimes: Robbery, assault, identity theft, child abuse and homicide.

Toni Red Bear, a member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, was addicted to meth for more than three years.

"Being addicted is like having the devil on your shoulder,” she said. “You can be in the middle of the deepest, darkest despair in your life where you don’t want to live if you don’t have the drug. Then you go get your fix and you feel healed."

Today, Red Bear counsels other addicts as a case manager for the tribal health department. But she still suffers from the longer-term effects of meth use.

“Before I used meth, I could remember anything and everything. I was good at math. Now I can’t even remember five items on a 10-item grocery list,” she said.

She says that even when addicts are brought into the health-care system, there aren’t enough resources to treat them. Meth treatment costs substantially more than most other addiction treatments and lasts substantially longer, often over a year.

Youth, elders fighting back

“The biggest impact of meth is on the children,” said Ebony Tiger, 17, a member of South Dakota’s Yankton Sioux tribe, among whom meth has replaced alcohol as the drug of choice. “They don't get the things they need because their parents or whoever they live with use the little money they have to get the drug."

She should know. Her mother has been a meth addict since Ebony was an infant. “I never felt the love a child should feel by his or her parent,” she said.

“I was left here and there with people I did not know and people who were also alcoholics and drug addicts. I never really had a place to call home until one of my aunts took me in,” she said.

Today, with the help of one aunt, she chairs Native American Youth Standing Strong, a community group working to discourage Native youth from experimenting with drugs.

Julie Richards, an Oglala Lakota mother and grandmother living on the Pine Ridge reservation in South Dakota, remembers when she first learned about the dangers of meth.

“One day back in November, 2005, my friend Connie’s daughter Chantel was home alone when someone knocked at the door.”

The visitor was an older woman who convinced Chantel, 15, to smoke meth for the first time. The girl took only one “hit.” A short time later, she complained of a headache and collapsed dead from a brain aneurysm.

“I’ve been on a personal vendetta against meth ever since,” Richards says, adding that her own daughters have struggled with addiction. “I started finding out who the meth dealers were and then I would put their names out there, publicly shaming them on Facebook.”

Richards organized the Mothers Against Meth Alliance (MAMA), a group of mothers who go out nightly to confront the dealers.

“Sometimes it’s just three of us, four if we’re lucky. Sometimes it’s just me and my kids,” she said.

Her work has put her at risk.

“I’ve had my car windows bashed out, twice,” she said. “And I’ve had a gun pointed at my face. When I call the police, either they don’t respond or they take an hour to show up. And nobody is ever arrested.”

She believes that tribal police, like everyone else, are scared: “Of the dealers, of the dealers’ families.”

But that may be simplifying the problem.

Limits of law enforcement

The Oglala Sioux Tribe’s Department of Public Safety consists of fewer than 100 sworn officers serving about 40,000 residents over more than 800,000 hectares.

“A cop can be 100 miles [160 kilometers] away from the crime scene, but he’s not just dealing with meth, but child abuse, domestic disputes, robbery, assault, drunk and disorderly or driving under the influence of alcohol,” said one Lakota man who asked not to be named.

He suggested that police may deliberately turn a blind eye to meth buyers and sellers.

“Everyone on the reservation is related,” he said, a reference to tiospaye, a Lakota concept of extended family that can include dozens, even hundreds.

“So if you're a cop, that might be your little nephew out there using meth. Or your mom or your brother. And if you arrest your mother for dealing and send her to prison for 10 years, what are your brothers, uncles, nephews and her customers going to do to you, your wife and children?”

Coppel admits there is a degree of corruption in many – “not most” - tribal leadership councils, law enforcement agencies, and courts. And for this reason, some tribe members may be reluctant to call upon the very agencies that exist to protect them.

VOA made repeated calls to the Oglala Lakota Sioux Tribe Department of Public Safety and Attorney General's Office requesting comment, but our calls were not returned.

Looking into the past for answers

Some tribes have turned to traditional practices.

The Lummi Tribe of Washington State, the Lac du Flambeau Band in Wisconsin, the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe in North Dakota and others have resorted to banishment and dis-enrollment of members convicted of dealing, making or trafficking meth.

Historically, banishment placed tribe members at the mercy of the wilderness. Today, it means being separated from loved ones and possibly losing out on health, housing, and education benefits. But punishment may not be the answer.

“We’re never going to arrest our way out of this problem. It requires a community solution - treatment and all the necessary psychosocial support, a context in which the recovering addict can find a job, have family and spiritual support,” said Copple.

"Throwing federal dollars at reservations isn’t effective either, not unless the various federal agencies coordinate with one another and with local public health, law enforcement and other agencies, he said. “If we could break down those silos to come up with coordinated approaches where the tribal communities themselves own the issue and own the solutions, then I believe there is hope.”

But some tribal members aren’t so sure.

“The drug war is over,” said one Lakota native, gloomily. “The drugs have won.”