Thailand is facing wide criticism for legalizing cannabis before putting sturdy guardrails against its abuse in place, and doubts the authorities can do much to stem a likely rise in its recreational use.

Marking a first for Asia, Thailand pulled cannabis from its list of narcotics on June 9, making its import, export, production, distribution, consumption and possession legal. Anyone can now grow the plant at home, after registering with the government via a mobile app, though commercial growers still need to apply for permits.

Public Health Minister Anutin Charnvirakul, who championed the plan, has tried to dissuade people from lighting up for fun, stressing the plant’s medical virtues and its potential as a cash crop. His ministry warns that anyone smoking cannabis in public can still be charged with causing a “nuisance,” fined $704 and spend up to three months in jail.

"Problems occur due to the abuse of cannabis. This is not the aim of liberalizing the use of the plant. We want to promote medical use and boost the income of growers,” Anutin told reporters last week.

But others in the government, and in his own ministry, say the move may be premature.

Somsak Akksilp, who heads Thailand’s Medical Services Department under Anutin, said he worried that legalizing cannabis without laws actually restricting it to medical use, and even then to adults only, could spur recreational use as well, which he opposes.

“That’s why I [have] said other authorities should try to issue the regulations as soon as possible [to] try to restrict the use of cannabis for ... medical cannabis,” he told VOA.

“Because we know that there is ... two sides of the coin, the good and the bad,” he added. “We know not much about the cannabis, so we have to learn more if we want to use for other issues.”

In a June 14 Facebook post, Mana Nimitmongkol, the head of the Thai government’s Anti-Corruption Organization, complained of the move to legalize cannabis without any controls “other than word of mouth.”

Much of the concern has focused on concerns of a coming tide of cannabis use among children and adolescents. The day after cannabis went legal, Thailand’s Royal College of Pediatricians issued an open letter urging the government to ban the use of cannabis and cannabis-laced products among those under 20 years of age without a physician’s approval.

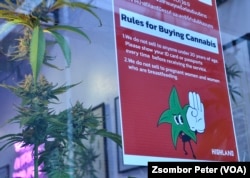

A few days later, Anutin signed an order adding cannabis to Thailand’s Traditional Medical Wisdom Protection and Promotion Act, denying the plant to not only adolescents but also pregnant women and breastfeeding mothers.

The municipal government of Bangkok, Thailand’s capital, and the Ministry of Higher Education have subsequently banned cannabis from public schools and universities as well.

Somsak said the piecemeal steps can help, to a degree.

“This is not through the law itself; it’s a kind of ... canton regulation,” he said. “If you want it to be the full regulation by law, you have to issue [it] by the parliament.”

A Cannabis and Hemp Bill meant to limit the plant’s use passed its first reading in parliament on June 8 but may have to wait weeks or months for the second and third readings it will need to become law.

The motley rules agencies are imposing in the meantime may help clear up what people now can and can’t do with cannabis. “But ... it’s still confusing,” said Rasmon Kalayasiri, director of the Center for Addiction Studies at Thailand’s Chulalongkorn University.

By legalizing cannabis use before legislating its boundaries, “it’s like we’re chasing the problem” instead of “preventing the problem,” she added.

Rasmon said her center’s own research suggests recreational cannabis use among 18 to 19-year-olds has doubled to about 2% of the age group since 2019. With the government now vigorously pushing the herb’s health benefits, she worries it will keep rising among adolescents and adults alike, and with it the health problems that afflict up to 1 in 10 habitual users, including addiction and psychosis.

“I think the public is very confused by this for sure,” Taopiphop Limjittrakorn, a lawmaker for the opposition Move Forward party, said of the government’s cannabis rollout.

Taopiphop says he supports laws that would ban access to children and adolescents and force edible cannabis venders to display the doses of intoxicating tetrahydrocannabinol in their products. But the self-professed “pothead” also favors recreational use, and doubts the government can now expect to rein it in having legalized cannabis before putting any strong checks in place.

“If you release the tiger to the jungle, it’s hard [to make it] come back,” he said.

Chokwan Chopaka called the rollout an irresponsible “free-for-all.”

A giant pot leaf in bright green neon lights marks the spot of her tiny cannabis shop, Chopaka, in central Bangkok. A hint of the cured flower’s sweet, trademark aroma hangs over the counter, where dried buds sit in clear glass jars with names like “blue gelato,” “banana hammock” and “orange deluxe sugarcane.”

Determined to sell responsibly, Chokwan took it upon herself to bar sales to anyone under 20 years of age even before the government told vendors to do so. When the buds are around, “even my daughter has to wait outside,” she said.

The shop opened in March selling cannabis-flavored gummies but saw a sharp spike in business as soon as it started selling the real thing on June 10. Chokwan said she’s sure most of her customers are smoking for fun, and believes they should have the right, just as with alcohol. But rather than trying to legislate the risks away, she believes the government could also be doing more to teach people how to use responsibly.

“This time is the time when we should educate, not just put it back into a cage and then expect people to not use,” she said, “because there’s no bloody way you can stop people from getting high.”

Anutin’s office referred VOA’s requests for an interview to the ministry’s Food and Drug Administration, which referred questions back to Anutin’s office.