From his office in the southern Afghan province of Kandahar, Taliban supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada has appointed ministers to Afghanistan’s de facto government, governors for the 34 provinces, and even a supreme court chief justice through “decrees” which do not need approval from a legislative body. There is one national institution, though, whose fate Akhundzada has yet to decide — the Afghanistan Independent Human Rights Commission (AIHRC).

Nearly seven months after the return of the so-called Islamic Emirate of Afghanistan, the Taliban’s emir, the commander of the faithful as he is officially called, has neither appointed new commissioners to the national rights watchdog nor instructed its nearly 400 employees to return to work.

Unlike Afghanistan’s elections commission, which the Taliban decided to abolish saying there will be no more presidential or parliamentary elections in the country, the future of the human rights commission remains uncertain.

Sohail Shaheen, a Taliban official, told VOA the AIHRC has not been abolished, but he could not explain why the rights monitoring body remains leaderless and dysfunctional.

The AIHRC has gone silent at a time when there are mounting concerns about a worsening human rights situation in Afghanistan.

Human rights groups have accused Taliban authorities of adopting misogynistic policies, restricting free media, and perpetuating other forms of egregious human rights violations — charges the Taliban deny.

“It's crucial for any country to have independent human rights bodies… for Afghanistan it’s even more important,” Juliette Rousselot, an expert with the International Federation for Human Rights, told VOA.

Activists gone

Last August, when the former Afghan government collapsed, all nine AIHRC commissioners, including its chairwoman, fled the country, fearing retribution from the Taliban. For almost two decades, the AIHRC had reported on serious human rights violations by the Taliban, including allegations of war crimes, and crimes against humanity committed by some Taliban commanders.

The flight of human rights activists from Afghanistan has been seen beyond the AIHRC commissioners.

The Dublin-based Frontline Defenders, a non-government organization advocating the safety of human rights activists, says it helped evacuate more than 1,000 Afghan human rights defenders and their immediate family members last year.

There are more than 2,000 additional individuals in the same category, who are waiting to be taken out of Afghanistan, Adam Shapiro, head of communications at Frontline Defenders, told VOA.

Thousands of other civil society activists, including journalists and artists, have left Afghanistan, and hundreds of media outlets there have stopped operations.

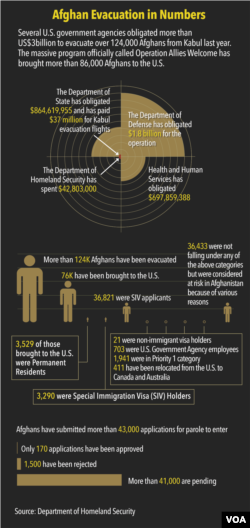

In the first two weeks after the fall of the previous Afghan government, the U.S. military evacuated more than 124,000 Afghans, according to official figures from the U.S. government.

Despite the exodus of many rights activists, some Afghans, particularly women’s rights activists, have continued to call for rights, freedom and justice in Kabul and some other cities across the country. Taliban authorities have at times detained women’s rights activists and beaten journalists, according to independent watchdogs.

Advocacy from abroad

“I have spent the past few months reflecting on the human rights journey of Afghanistan & the implications of the current situation on the future of human rights in the country,” Shaharzad Akbar, the last chairwoman of the AIHRC, told VOA.

Akbar and several other Afghan women have continued to advocate for the rights of Afghan women and minorities from Europe, Canada and the U.S.

Last month, the European Parliament organized a two-day event in support of Afghan women at its headquarters in Brussels. In the U.S., a group of Afghan and international women rights activists have created an organization called the Women’s Forum on Afghanistan, with former Swedish foreign minister Margot Wallström as its chair.

Several Afghan women have received international prizes for their courage and resilience in the face of growing Taliban restrictions inside Afghanistan.

This widespread international support has given hope for the self-appointed acting chairman of the AIHRC, Naim Nazari, to explore the possibilities of reconstituting the watchdog in exile.

“The Taliban has no legitimacy,” Nazari told VOA from his home in Denmark, adding that the AIHRC would have no independence under a Taliban government.

Nazari said he has approached some donors to seek their support for a reconstitution of the AIHRC in exile. “This will depend on support from the international community,” he said.

From its founding in 2002 to its abrupt disintegration in 2021, the AIHRC, whose role was also enshrined in article 58 of Afghanistan’s 2004 constitution, was sponsored by Western donors. In 2020, for instance, 75% of the AIHRC’s $5.2 million budget was funded by Australia, Canada and several European countries.

There are others who consider the work of the AIHRC from abroad unfeasible and ineffective.

“The human rights commission cannot operate only from a Twitter handle,” said a former AIHRC official, who asked for anonymity. “You need to be on the ground to monitor, verify and substantiate the events and be able to talk to all sides.”

Caught between the Taliban’s disinterest in human rights reporting and the inability of the human rights activists to work under the Taliban, Afghanistan’s only human rights body remains inactive at a time its most needed.