He regularly meets foreign diplomats and speaks in public but is also the FBI’s most wanted man in Afghanistan.

Sirajuddin Haqqani, the Taliban’s acting interior minister, even appeared on CNN on Tuesday with a conciliatory message for Americans. “In the future, we would like to have good relations with the United States,” he told CNN anchor Christiane Amanpour, who donned a green headscarf for the rare interview.

Last week, Tomas Niklasson, the European Union’s special envoy for Afghanistan, met Haqqani in Kabul and urged him to reopen secondary schools for girls. Last month, Haqqani spoke with Martin Griffiths, the United Nations’ under-secretary-general for humanitarian affairs and emergency relief coordinator, about the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Afghanistan.

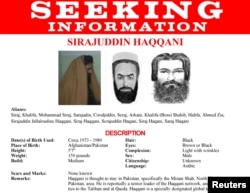

Haqqani’s public appearances stand at odds with a U.S. call for information about his whereabouts. Reward for Justice, a U.S. Department of State program aimed at combating international terrorism, offers $10 million for information that will lead to Haqqani’s arrest.

“The bounty on Siraj[uddin] Haqqani at this point is meaningless,” Asfandyar Mir, a senior analyst at the U.S. Institute of Peace (USIP), told VOA. “Haqqani is now one of the main — if not the main — interlocutors for the international community in Afghanistan.”

The U.S. government does not recognize the Taliban’s de facto government and has closed the U.S. embassy in Kabul indefinitely. There is no indication U.S. officials have met with Haqqani.

U.S. officials have, however, met with Haqqani’s younger brother, Anas Haqqani — who is not wanted — during talks with Taliban representatives in Qatar. In addition to Sirajuddin Haqqani, the U.S. government is offering a $5 million bounty on Abdul Aziz Haqqani, another younger brother of Sirajuddin, and $3 million for Khalil Haqqani, Sirajuddin’s uncle and a current Taliban cabinet minister.

Heirs to insurgent commander

The three most wanted Haqqanis are heirs to Jaluluddin Haqqani, the late Afghan guerrilla commander who allegedly received U.S., Saudi and Pakistani support to fight the Soviet army in Afghanistan in 1980s. Jaluluddin died from an unspecified illness in 2018 at age 78.

While functionally part of the Taliban group, the Haqqanis run a distinct terror, kidnapping and criminal enterprise known as the Haqqani network, or HQN. In 2012, the U.S. government designated the HQN as a foreign terrorist organization, accusing it of perpetuating terrorist attacks against U.S. personnel and Afghan allies in Afghanistan.

“Siraj[huddin] Haqqani is very powerful in the Taliban government,” Graem Smith, a senior analyst at International Crisis Group (ICG), told VOA, adding that under restructuring, the Taliban have brought in the Afghan government and that the administration of all of Afghanistan’s more than 300 districts fall under Haqqani’s writ.

The HQN reportedly enjoys strong backing from Pakistan. In 2011, Michael Mullen, then chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, described the HQN as “a veritable arm of Pakistan's” intelligence agency — a charge Pakistani officials dismissed immediately.

Both the Taliban and the Haqqanis have denied the very existence of the HQN as an independent group.

As one of the two deputies to the Taliban’s supreme leader Hibatullah Akhundzada, Siraj Haqqani is in line to be the Taliban’s next top leader.

A political tool?

“The Rewards for Justice program has been very successful,” a State Department spokesperson told VOA. “Since its inception in 1984, the program has paid in excess of $200 million to more than 100 people across the globe who provided actionable information that helped prevent terrorism, bring terrorist leaders to justice, and resolve threats to U.S. national security.”

In 1997, the program paid for information that led to the arrest of Aimal Kansi in Pakistan. Accused of killing two Central Intelligence Agency employees and wounding three others in Virginia in 1993, Kansi was tried in the U.S. in 1997 and subsequently executed in 2002.

Despite other successful prosecutions, some analysts question the validity and overall effectiveness of the program.

“The Rewards for Justice program has long been a way to make a political point against high-value individuals — and not a real law enforcement, intelligence collection or targeting tool against them,” said Mir of USIP.

In addition to setting monetary rewards for their arrest, the U.S. government imposes strict sanctions on designated terrorist individuals and entities.

With the Taliban’s return to power, the U.S. and the U.N. have extended strict financial sanctions over Taliban-controlled Afghan state institutions, and against the designated terrorist groups themselves, including the Taliban and HQN.

But some observers say the sanctions alone don’t do enough to keep the groups in check.

“The stigma of sanctions is not hurting the Haqqanis, who enjoy power in Kabul, but the sanctions continue to affect the Afghan economy,” said the ICG’s Smith.

Afghanistan’s per capita income has fallen by more than one-third since the Taliban seized power last year, prompting one of the worst humanitarian crises the landlocked country has experienced, according to aid agencies.