A blindfold prevented Jalal Nofal from seeing the prison guard who asked him for medical advice.

The Syrian psychiatrist was startled, but listened as the guard listed his ailments and his struggle to lose weight. It sounded like an ordinary consultation with a physician, not a conversation between a jailer and a blindfolded prisoner who had just been beaten.

The encounter in one of Syria’s notorious prisons took place during Nofal’s first term behind bars—eight years that interrupted his medical studies during the 1980s, when the current Syrian ruler's father, Hafez al-Assad, was in power.

Like father, like son

As if not to be outdone by his father, President Bashar al-Assad has had Nofal imprisoned or detained four times—albeit for much shorter periods—for his political opposition to the dictatorship. One of the psychiatrist's incarcerations in 2012 was accompanied by especially fierce torture at a detention center run by Syrian air force intelligence, generally viewed as the most vicious of the security branches.

But to return to the overweight prison guard, Nofal recalls, “I told the guard what he should do.” A few days later he was escorted without a blindfold for his weekly shower and saw a “very fat guard, who I realized was the one who had asked me for advice.” Nofal recommended two different medications, but realized later they might interact if the guard took them together. So the next day he warned the jailer not to take them at the same time.

“You care about my health?” the guard said. "'Of course, you are now my patient,' I told him.” Slowly at first, other guards began coming to him for medical advice, and he became less of an enemy to them. Prison conditions for him improved, but only a little.

Using experience to help others

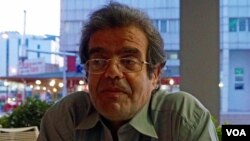

For a man who has endured prolonged detention and torture and who has watched his country torn apart by a terrifyingly brutal conflict that has left hundreds of thousands dead, the 53-year-old Nofal remains remarkably hopeful. He has counseled anguished people who suffered appalling torments or witnessed terrible events.

In Turkey's border town of Gaziantep he now treats the walking wounded—Syrians who have fled the battlefront but still are burdened by suffering.

Nofal was smuggled into Turkey in December 2014. His wife had fled Syria more than a year earlier with the security agencies hard on her heels. He decided to leave when he realized the regime was planning to bring terrorism charges against him, which would mean he would probably never get out of prison.

“I couldn’t do anything constructive [while remaining in Syria] because people would ask me to stay away from them, for fear they, too, would be arrested," he recalls. "I thought I [would] be arrested for doing nothing, so why should I remain?”

Psychology of survival

In Turkey, he has treated women who were raped while in detention, counseled those who have survived massacres or watched their spouses and loved ones blown to bits. Recently he has been monitoring the mental health of three kids who witnessed other children in Raqqa playing football with the heads of decapitated captives, egged on by Islamic State fanatics.

Nofal relates this all calmly.

“Yes, there are stories that are really surprising,” he says with dry understatement.

As we sit outside drinking tea near dusk, he tells me about a woman he is treating who cannot tell whether she buried her husband or a stranger.

“During a massacre she found three bodies, burnt and terribly disfigured,” he says. “She had to guess which was her husband. Now she is wracked by guilt. She fears she buried someone who was not her husband. It is torturing her.

“Being a psychiatrist helped me in prison; my prison experiences help me as a psychiatrist now to treat others,” he says.

Aside from physical injuries caused by brutal beatings and medieval-style tortures, inmates in Assad's prisons risk being overcome by psychological disorders resulting from their treatment.

Survivors tell of many fellow detainees who gave up, stopped eating or drinking and later died in their cells. Nofal’s psychiatric knowledge equipped him to cope with the mental distress of detention and torture, and he tried to pass that on to other detainees.

His knowledge of human behavior guided him to understand the guards and interrogators and their psychological need to preserve their sense of superiority.

“So give that to them, but don’t give them information. Or if you do, make them think it is important, but make sure it only relates to you and not others,” he says. "Make them think you have surrendered.”

His hope now rests on his faith in human resilience, and on Syria’s strong social networks. The Syrian refugees he works with are people who have not surrendered, but have endured. They are not former detainees, he says, but "survivors."

Counseling youth

It is school graduation night in Gaziantep, and as we talk, giggling Turkish teenagers troop past, self-conscious in their long party dresses and high heels. Maybe their youthfulness prompts Nofal to tell me about a 15-year-old Syrian girl he is counseling who lost both her parents to the war.

“She is a teenager but has the role of the mother for her two siblings and she says of them that they should live a better life than her," he says. "She speaks as though she is 70 years-old, but she is so resilient and focused on raising her younger sisters. She has not surrendered. And she isn’t complaining about her losses—the deaths of her mother and father, the fact that she can’t go to school. We shouldn’t tell her what she has endured and is going through isn’t too much — we should say, ‘You are well but we want to help you and to support you and your siblings.’”

Refugees, he adds, are helped and hobbled by the new lives they assume. Their insecurity in a newly safe place can become the basis for anxiety and depression.

“It is hard enough even if you have not been traumatized before you arrived. You have to explain to them they are having normal reactions to abnormal experiences," he says. "You teach them self-care. You try to empower them."

That is harder to do for those suffering full-blown post traumatic stress disorder, such as the woman who survived two of the worst Assad massacres in the Syrian conflict but can no longer sleep, because she fears that Shabiha [government thugs] will come and snatch her children. Or the women who have debilitating flashbacks of being raped and degraded, and the fathers who see the violent deaths of their children again and again in their minds.