The Islamic State group has been losing large swaths of territory to Western-backed Syrian Kurdish fighters and the Iraqi military supported by Shi'ite militias, but a key ingredient in the fightback against jihadists is missing — local tribes are not turning en masse against Islamic militants in Syria or Iraq.

U.S. and anti-IS coalition allies have been seeking to replicate the Sunni Awakening of 2006, when a Washington-coaxed tribal uprising was a key element in assisting U.S. troops to drive al-Qaida jihadists from Iraq’s westernmost Anbar province.

Despite the appointment of John R. Allen in 2014 as special envoy to coordinate the international effort to combat IS in Iraq and Syria, a repeat of the Sunni Awakening has not materialized.

Allen had been a key figure in 2007 efforts to persuade more than 30 tribes in Anbar province to turn on the Islamic militants, offering protection and financial incentives if they would reject the radical Sunnis; but, he relinquished his special envoy role in October without having pulled off a similar feat.

Limited impact

A mass uprising of local tribes in Syria or Iraq still seems a distant hope rather than a reality. A trickle of tribesmen in Iraq has joined coalition forces, but not the flood that was expected, says Charlie Winter, an analyst with the London-based Quilliam Foundation.

He says much of the reason for the absence of a tribal uprising lies with IS efforts to keep the tribes in line. “IS has been working on tribal relations for a very long time now.

“The networking infrastructure IS has established, principally in the form of the Diwan al-'Asha'ir [Diwan for Tribal Outreach], enables it to anticipate and carefully respond to the complex tribal dynamics of Iraq and Syria. It also seems to be attempting to play the role of honest broker in intra-tribal conflicts, mediating animosity and drawing adversarial tribes together. In short, it has a very nuanced approach.”

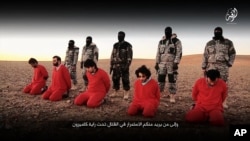

"Nuanced" may be a description some recoil at, as IS has been engaging in brutality and massacres in policing tribes in eastern Syria and western Iraq to ensure their fealty. One of its biggest massacres came in August 2014 when IS fighters took vengeance against the Sha'itat tribe in eastern Syria — beheading, crucifying and shooting more than 700 people in a three-day period.

Formidable adversary

The lesson for tribesmen was that rebellions inside Syria against IS aren't equipped to take on the powerful militants and attract scant outside help when they do take place.

Across eastern Syria and western Iraq, the militants of the Islamic State group govern with an iron fist and a sharp eye, purging opponents and are intolerant of expressions of dissent.

Relying on an extensive network of spies and informers to ferret out dissent or any behavior that falls afoul of their strict interpretation of Sharia, they are alert for any signs of a tribal insurrection shaping up against them.

The killings serve as a warning to others; but, there is nothing to offset the heavy IS hand.

“There’s no large-scale actor the tribes in Syria in particular can turn to for support,” says Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, a research fellow at the Middle East Forum. He notes the August 2014 massacre to suppress the Sha'itat revolt was partly put down by other Sha'itat members working for IS.

Lack of ground support

Daveed Gartenstein-Ross, an analyst with the Foundation for Defense of Democracies, blames a “lack of U.S. leadership.” He says there is an absence on the ground of “appropriate actors who can foster such an uprising, and dedicate resources to doing so.” He faults the international coalition for failing to reach out before the fall of Ramadi consistently to tribes who had participated in the original Sunni Awakening in Anbar province in 2006 and 2007.

Hoping that eventually the barbarity of the Islamic militants will prove to be their downfall doesn’t serve as a strategy, he maintains. And the highly complicated and sectarian politics unleashed by the micro-conflicts in the Syrian war and Iraq battles are pulling against a tribal uprising, he says. In Iraq, the Shi'ite-dominated government is not in a position “to rally Sunni tribes who have been burned by it before,” says Gartenstein-Ross.

Sunni tribesmen don’t trust a government that has refused to arm them and relies mainly on Shi'ite volunteers in the popular mobilization committees to fight IS. “They deter rather than encourage Sunni tribal participation,” says Gartenstein-Ross.

Sunni Arab tribes in Raqqa province in Syria issued a statement last month accusing the Western-backed Kurdish forces of the People’s Protection Units (YPG), of displacing Arabs from the Tal Abyad town on the border crossing with Turkey.

They warned, “No YPG fighter can enter the Arab areas where our fighters are present.”

The Kurds deny they have forced Arabs to leave Tal Abyad or other mainly Arab villages in northeast Syria they have overrun.