Less than a day before a high-profile hearing in the legal standoff between Apple and the FBI, attorneys for the Department of Justice late Monday persuaded a federal judge to cancel the hearing and issue a temporary stay in the case.

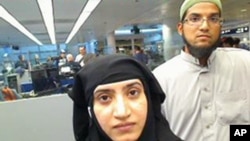

At issue was an earlier order by U.S. District Judge Sheri Pym ordering engineers at Apple to create a software patch to assist FBI analysts in unlocking an iPhone allegedly used by Syed Farook, one of the two shooters in December’s San Bernardino terror attack.

From the beginning, the FBI argued it was unable to crack the phone’s security features and needed Apple’s help to search the phone’s contents.

In filings to Judge Pym, though, U.S. Attorney Eileen Decker said that just last weekend “an outside party demonstrated to the FBI a possible method for unlocking Farook’s iPhone.” Pym temporarily stayed her previous order, giving the government until April 5, when it must present a status report.

The sudden move is raising questions not just about this case, but also about the FBI’s technical capabilities, as well as larger government efforts to limit encryption on personal devices.

What’s the status of the iPhone?

The FBI is not saying who the third party is or what technique they’ve proposed to bypass the iPhone’s auto-erase function, which permanently deletes all data on the phone after 10 incorrect guesses at the password.

For its part, Apple has not made any public statements regarding the government’s filing. Instead the firm is limiting its comments to this week’s introduction of new iPad and iPhone models.

A number of digital forensics analysts have proposed a variety of possible methods over the last several weeks, including duplication of the flash memory or reverse engineering of the iPhone’s internal circuitry. None of these techniques have yet been proven effective.

Computer anti-virus pioneer John McAfee has publicly called breaking into an iPhone “a trivial matter” and personally offered to help the FBI free of charge – an offer the FBI declined.

How does this new info change legal arguments on both sides?

If the new technique is unsuccessful, FBI attorneys likely will say that bolsters their argument that only Apple engineers can help break into the phone without destroying data. And because the stay is only temporary, the Justice Department could ask Judge Pym to reinstate her order, putting the matter back to square one.

Assuming that, the judge again will be asked to rule on Apple’s request to vacate her earlier order, as she had been scheduled to do Tuesday.

Whatever her ruling, it’s all but guaranteed the case will be appealed, perhaps all the way to the Supreme Court.

On the other hand, if the unnamed third party can successfully unlock the phone, this specific legal case would end. Apple attorneys likely would continue, however, to argue that the FBI never really needed Apple’s help to begin with, and shouldn’t be required to provide assistance in the future.

If successful, will the courts be finished with this issue?

Most observers think that’s unlikely. Apple, along with other tech companies, say they intend to offer even more robust encryption and security features to consumers in the future, while the FBI continues to expand its “Going Dark” initiative to slow the spread of unbreakable encryption.

Because both the FBI and the tech industry are hoping to establish a legal precedent to guide future requests, it’s probable both sides will continue to look for the perfect test case that presents the strongest legal argument for their case.

Are the courts the only way to settle this dispute?

No. Here in the U.S., members of Congress may feel pressured to act if the legal challenge drags on too long. Already, two influential politicians have proposed a national commission to study the competing demands of privacy and security in order to promulgate legislation governing encryption.

Privacy and encryption also are topics of concern for the European Court of Justice, the EU’s highest court. In several cases, most recently in 2014, the court has ruled that all individuals have a fundamental right to privacy online.

Any laws requiring companies like Apple to provide the FBI with some form of access to break into devices may well be challenged there; the resulting decisions could have major economic consequences for the mobile industry.