Conflict and political upheaval in Sudan and turmoil in other parts of the Africa region have sent thousands of refugees fleeing their homelands in the hope of finding better lives for themselves and their children. Many are heading to Egypt, where the influx is causing a serious strain on resources.

One refugee from the Sudanese capital Khartoum, El Hadi Osman, tells VOA that he fled Sudan because of religious persecution. Hadi worked as a writer and journalist until Sudanese police targeted him for becoming a Christian.

"(In Khartoum)," he says, "police told me to stop going to church and renounce my faith, but I said no." "When they jailed me," he confides, "they beat me and hung me upside down in prison." "I have torture marks on my body," he says sadly, "pointing to scars on his arms and shoulders."

El Hadi says that he fled to Cairo in 2014 after spending weeks in a Sudan jail. "I was living in fear," he insists, "crossing the street to escape shadows that were chasing me." "My old friends," he remarks, "deserted me and I became a lonely man."

WATCH: Sudanese refugees tell stories after fleeing

After spending weeks in an overcrowded cell and eating lentils twice a day, el Hadi was released. He fled to the north of the country and entered Egypt, heading by foot and by bus to Cairo, where he spent weeks sleeping on a sidewalk in a slum. In Cairo, he turns to refugee agencies for odd jobs to survive.

As young people march for freedom on the streets of Khartoum, Sudanese refugees in Egypt - like El Hadi - keep a watchful eye on events back home. Many dream of returning home if political change pulls down the current regime.

Sudanese refugees, like Adel Youssef Salah, who fled war-torn Darfur after enduring years of strife, has an enthusiastic glint in his eye as he talks about the current wave of protests that have swept across his homeland.

“I hope the Sudanese people," he insists, "will seize (their) destiny, and make the (President Omar Hassan al Bashir) chart a course towards democracy.” Bashir came to power in 1989 in a military coup which ousted then Prime Minister Sadeq al Mahdi.

Despite the struggles of daily life, Salah says Egyptians have been kind to him. "Egyptians are not wealthy," he points out, "but they usually share what little they have."

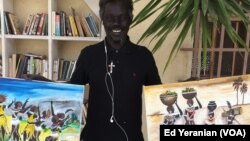

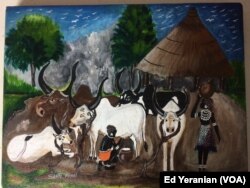

Santo Makoi is a political refugee from South Sudan. He studied fine arts at Sudan University in the north of the country before the south became independent in 2011. He worked for a European NGO called War Child, teaching refugee children to draw and paint.

Santo tells VOA that he moved to Juba when the south became independent but "quickly fell afoul of the new authorities controlling the country because of his caricatures, drawings and cartoons of prominent people." Santo is registered as a refugee with the UN, but continues to paint and draw at a studio run by an Egyptian charity group.

Nour Khalil, an immigration lawyer, says the refugee crisis in Egypt is even worse than the official figures suggest. Tens of thousands of Syrians, Yemenis, Ethiopians, Eritreans and Libyans have left their countries for Egypt due to the plethora of conflicts raging in the area. Many are not officially registered with the UNHCR.

"230,000 refugees are officially registered with the U.N. in Egypt," says Khalil, "but no one knows their real number." Egyptian President Abdel Fattah el-Sissi confided to German Chancellor Angela Merkel in 2017 that Egypt had over five million refugees in its territory.

During a recent gathering of heads of state and government from Europe and Africa, Sissi told his counterparts that Egypt is heavily burdened by the many refugees on its soil.

"Egypt is hosting millions of refugees," he asserted, "offering them schooling and health care, despite the difficult circumstances the Egyptian people themselves have gone through in recent years." He stressed that Egypt has "prevented boat-loads of refugees from leaving its territory for Europe since 2016."

The U.N. refugee agency (UNHCR) says Egypt has given refugees safe haven and in some cases the right to work, to health care and to schooling. UNHCR spokesperson Shabia Mantoo tells VOA that the U.N. "makes sure that they have access to basic services and are also supported and protected in the best way we can."

Mantoo points out, however, that the current anti-refugee sentiment in many countries is hindering the work of her organization, since "only 55,000 refugees out of millions were resettled (by UNHCR) in other countries, last year." She also points out that many countries have been late in paying their normal contributions to UNHCR, making the group's work even more difficult.

Refugee agencies are also complaining of "donor fatigue." One foreign refugee agency volunteer told VOA that "at least two major U.S. charitable organizations were expected to pull out of Egypt, next year."

In the meantime, the life of a refugee in Egypt has become a struggle, so much so that many go on to Libya and from there, try to reach Europe by boat - a journey that a lot of them do not survive. Many others have also found themselves in detention in a Libyan jail cell, where inhuman conditions have been reported.