Sudan Thursday hanged six men convicted in the murder of 13 policemen five years ago during a forced eviction operation in the capital, Khartoum. The clashes erupted in May, 2005 as police tried to empty out the Soba Aradi neighborhood that housed 10-thousand victims of Sudan’s north-south civil war.

18 months later, a Special Military Court issued the death sentence for seven defendants in the violent clashes. Many Sudanese arrested in the riots were acquitted. But last week, defense attorneys said the three-year appeals process for six remaining suspects had been exhausted, and they were executed on January 14. A seventh defendant received a reduced five-year jail sentence.

Amnesty International immediately condemned the executions. Amnesty Sudan researcher Rania Rajji charged that prosecutors had obtained forced confessions, and the judicial process did not permit any investigations or cross examination.

“Amnesty International believes that their confessions were extracted under torture. Their lawyers have tried the defense of torture against their confessions, which were used as a main element towards their sentences. But the judges issued the dissent. There was never an investigation into the incident to start with, so there is no way of knowing whether these people were really involved. We think that there were unfair trials,” said Rajji.

Since June, 2008, Sudan’s Special Military Courts have handed down more than 100 death sentences in trials that human rights groups say have failed to satisfy international fair trial standards. Sudan hurriedly set up the special courts in May, 2008 to prosecute suspects accused of taking part in the May 10 attack on Khartoum by the Justice and Equality Movement (JEM) rebel group.

Amnesty’s Rajji says the Khartoum government has used the courts’ recently expanded power to pursue severe penalties against other offenders, including the Soba Aradi squatters, whose case began two years before the Special Military Courts came into being.

“The problem with the Sudanese judicial system is that the legal battle is not really allowed. Since 2007, the six men had been sentenced to death. The courts only did confirm the death sentence, and the death sentence had been on hold. And basically, the judges decided to immediately execute. So it is always a matter of an unfair trial,” she said.

Even before Sudan expedited the powers of the judiciary to convict, Rajji points out that Sudanese courts have had a long history of punishing suspects with the death sentence, and there continue to be a growing number of executions in the country.

“Sudan has always been high on the list of countries executing. There are retorts from 1997 already placing Sudan high on the list. There has been a culture of political death sentences and executions. You have seen over the last year that there were between June, 2008 and June, 2009 107 people who were sentenced to death in relation to the attack by the Justice and Equality Movement on Khartoum. We believe that all of them had an unfair trial. This is only an indication of how politicized justice is in Sudan,” she noted.

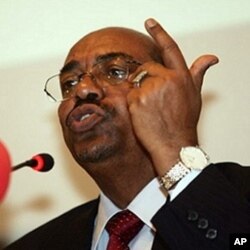

With Sudan’s President Omar Hassan al-Bashir currently under indictment by the International Criminal Court in the Hague, Rania Rajji says that nations need to tighten their vigilant monitoring of Sudan’s judicial practices. But she contends it is ultimately Sudan’s own responsibility revamp their harsh system of justice as well as to cooperate internationally by handing over all suspects accused of war crimes to the International Criminal Court.