The demand for food crops is growing, but experts say the world’s harvests are not keeping pace.

A new study pinpoints exactly where crop yields are falling behind. The authors describe it as “actionable intelligence” on where more investment is needed to help secure the world’s food supply.

The United Nations says there will be 2 billion more people to feed by 2050. And people are becoming richer and eating more meat, which takes more grain to produce; and demand for plant-derived biofuels is growing.

But while the need for food crops in increasing, the new study found productivity has flattened out or declined on 43 percent of the world’s rice-growing land, and 44 percent of its wheat fields.

"Where are we heading?"

That raises a serious question, according to lead author Deepak Ray at the University of Minnesota.

“If huge tracts of rice and wheat areas are not improving," he asks, "then where are we actually heading in terms of reaching that target of feeding 9 billion humans?”

Overall, Ray says, the new study found yields were stagnant or fell on about a quarter to two-fifths of the world’s farmland growing rice, wheat, corn or soybeans. Those four crops account for about two-thirds of the world's caloric consumption.

Other studies have warned that crop yield increases are not keeping up with demand. But Ray says they have been too vague to act on.

“When you say, for instance, wheat yields are not increasing anymore in India, it doesn’t really say much. It doesn’t say where it is not increasing.”

County by county

So Ray’s team pored over decades of official figures and detailed statistics, “to figure out what is happening in each county, for example in the United States, or in each municipio in Brazil or in each district in India... It takes a long, long time, obviously.”

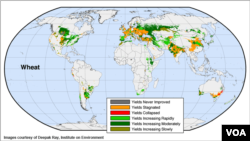

It took three years, in fact. But in the end, the group produced detailed maps that can be used to zero in on where yields are increasing and where they are not.

But Ray says this is really just the beginning.

“This data set can be used to answer many other questions like, ‘Where are we going from here?’ What we have only shown is where we are right now.”

Next, Ray says, researchers need to figure out why yields are not improving in these areas and what needs to change.

"Good news"

Kostas Stamoulis, director of the Agricultural Development Economics Division at the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, says the study identifies areas where improvements would have a substantial impact.

“There is significant untapped potential to increase yields to accommodate future demand," he says. "This is good news. Let’s put it that way.”

And Stamoulis says in many cases tapping that potential is a matter of applying what is already known.

“The technologies exist, he says. "We have to provide farmers with market access, infrastructure, risk management practices that will incentivize them to use those technologies.”

And as the demand for food crops grows, Stamoulis says the time to invest in farmers is now.

A new study pinpoints exactly where crop yields are falling behind. The authors describe it as “actionable intelligence” on where more investment is needed to help secure the world’s food supply.

The United Nations says there will be 2 billion more people to feed by 2050. And people are becoming richer and eating more meat, which takes more grain to produce; and demand for plant-derived biofuels is growing.

But while the need for food crops in increasing, the new study found productivity has flattened out or declined on 43 percent of the world’s rice-growing land, and 44 percent of its wheat fields.

"Where are we heading?"

That raises a serious question, according to lead author Deepak Ray at the University of Minnesota.

“If huge tracts of rice and wheat areas are not improving," he asks, "then where are we actually heading in terms of reaching that target of feeding 9 billion humans?”

Overall, Ray says, the new study found yields were stagnant or fell on about a quarter to two-fifths of the world’s farmland growing rice, wheat, corn or soybeans. Those four crops account for about two-thirds of the world's caloric consumption.

Other studies have warned that crop yield increases are not keeping up with demand. But Ray says they have been too vague to act on.

“When you say, for instance, wheat yields are not increasing anymore in India, it doesn’t really say much. It doesn’t say where it is not increasing.”

County by county

So Ray’s team pored over decades of official figures and detailed statistics, “to figure out what is happening in each county, for example in the United States, or in each municipio in Brazil or in each district in India... It takes a long, long time, obviously.”

It took three years, in fact. But in the end, the group produced detailed maps that can be used to zero in on where yields are increasing and where they are not.

But Ray says this is really just the beginning.

“This data set can be used to answer many other questions like, ‘Where are we going from here?’ What we have only shown is where we are right now.”

Next, Ray says, researchers need to figure out why yields are not improving in these areas and what needs to change.

"Good news"

Kostas Stamoulis, director of the Agricultural Development Economics Division at the U.N. Food and Agriculture Organization, says the study identifies areas where improvements would have a substantial impact.

“There is significant untapped potential to increase yields to accommodate future demand," he says. "This is good news. Let’s put it that way.”

And Stamoulis says in many cases tapping that potential is a matter of applying what is already known.

“The technologies exist, he says. "We have to provide farmers with market access, infrastructure, risk management practices that will incentivize them to use those technologies.”

And as the demand for food crops grows, Stamoulis says the time to invest in farmers is now.