Severely malnourished children are more likely to survive if they receive antibiotics in addition to therapeutic feeding, according to a new study.

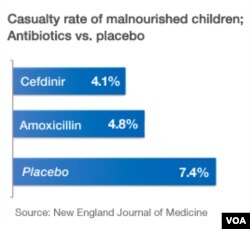

In the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, a week’s worth of common antibiotics reduced the death rate among severely malnourished children by 35 percent or more.

About 20 million children worldwide are severely malnourished, and malnutrition is a factor in the death of about 1 million every year. So the results are a big deal, says lead author Indi Trehan, a pediatrician at Washington University.

“If you can cut the death rate by 35 percent for any disease, that’s a huge finding," said Trehan. "And if you can do it with a $3 antibiotic, that’s an even bigger finding. And if you can do it with a $3 antibiotic and a disease that kills a million kids a year, 35 percent less deaths - that’s why we’re having this conversation today.”

Malnutrition stunts a child’s physical and mental development. It also affects their defense against diseases of all kinds, from pneumonia to malaria to measles. Trehan says that can be the difference between life and death.

“You can easily go into a village in the middle of a measles outbreak and hand-pick which ones are going to die," he said. "You can tell what’s going to happen based on how scrawny they are.”

Until a few years ago, those scrawny kids would have needed to be hospitalized to treat their malnutrition. And still, as many as half of them would die.

But with advances in ready-to-use therapeutic foods like Plumpy’Nut, a nutrient-fortified paste of peanuts and milk powder, these kids can be sent home and 85 to 90 percent of them recover fully. It’s a huge advance, Trehan says.

“But if 10 or 15 percent still don’t recover, and if 5 or 10 percent die, in a disease that hits 20 million kids a year, that 5 or 10 percent is still an outrageously large number that we can’t be happy with," said Trehan.

The Washington University pediatrician and his colleagues wondered if they could cut the number of deaths by sending malnourished kids home with antibiotics as well as nutrient-fortified therapeutic food.

Public health authorities have recommended antibiotic treatment for malnutrition for several years. But there has been no solid medical evidence for its benefits. And indiscriminate use of antibiotics carries a risk of side effects, including antibiotic resistance. Plus, there’s the added cost. So Indi Trehan’s group in Malawi had not prescribed them before.

But he says the new results quickly changed their minds.

“We were extremely shocked," he said. "I remember the night when we started looking at the data, and I had to call up the lead investigator, Mark Manary, and I said, ‘Can you believe this? This is actually happening.’”

“We were suspecting that this might be the case. However, we did not have any proof," said Myrto Schaefer.

Pediatrician Myrto Schaefer, with the relief organization Doctors Without Borders, says the group has been giving antibiotics to malnourished children anyway. But this is the first study to provide solid evidence for the practice.

“However, what we don’t know is whether the results of this study can be easily transferred to the areas where the majority of children with severe malnutrition live," said Schaefer.

Schaefer says severe malnutrition is most serious in the Sahel region of Africa. But malnourished kids there do not show the same symptoms as those in Malawi, where this study was done. That suggests the underlying causes are different, and go beyond just the lack of food.

In fact, Trehan is co-author on an accompanying study that suggests the types of microbes living in the Malawian children’s gastro-intestinal tracts may be contributing to their malnutrition.

“You could give them the right diet, but if the right bugs aren’t there to help liberate your zinc, or your vitamin A or your proteins, then you’re not going to really absorb them and use them for growth. And you’re going to get malnourished," he said.

Trehan acknowledges it's not really clear why the antibiotics are having the effect they are. He says that’s what he plans to spend the next several years studying.

In the study published in the New England Journal of Medicine, a week’s worth of common antibiotics reduced the death rate among severely malnourished children by 35 percent or more.

About 20 million children worldwide are severely malnourished, and malnutrition is a factor in the death of about 1 million every year. So the results are a big deal, says lead author Indi Trehan, a pediatrician at Washington University.

“If you can cut the death rate by 35 percent for any disease, that’s a huge finding," said Trehan. "And if you can do it with a $3 antibiotic, that’s an even bigger finding. And if you can do it with a $3 antibiotic and a disease that kills a million kids a year, 35 percent less deaths - that’s why we’re having this conversation today.”

Malnutrition stunts a child’s physical and mental development. It also affects their defense against diseases of all kinds, from pneumonia to malaria to measles. Trehan says that can be the difference between life and death.

“You can easily go into a village in the middle of a measles outbreak and hand-pick which ones are going to die," he said. "You can tell what’s going to happen based on how scrawny they are.”

Until a few years ago, those scrawny kids would have needed to be hospitalized to treat their malnutrition. And still, as many as half of them would die.

But with advances in ready-to-use therapeutic foods like Plumpy’Nut, a nutrient-fortified paste of peanuts and milk powder, these kids can be sent home and 85 to 90 percent of them recover fully. It’s a huge advance, Trehan says.

“But if 10 or 15 percent still don’t recover, and if 5 or 10 percent die, in a disease that hits 20 million kids a year, that 5 or 10 percent is still an outrageously large number that we can’t be happy with," said Trehan.

The Washington University pediatrician and his colleagues wondered if they could cut the number of deaths by sending malnourished kids home with antibiotics as well as nutrient-fortified therapeutic food.

Public health authorities have recommended antibiotic treatment for malnutrition for several years. But there has been no solid medical evidence for its benefits. And indiscriminate use of antibiotics carries a risk of side effects, including antibiotic resistance. Plus, there’s the added cost. So Indi Trehan’s group in Malawi had not prescribed them before.

But he says the new results quickly changed their minds.

“We were extremely shocked," he said. "I remember the night when we started looking at the data, and I had to call up the lead investigator, Mark Manary, and I said, ‘Can you believe this? This is actually happening.’”

“We were suspecting that this might be the case. However, we did not have any proof," said Myrto Schaefer.

Pediatrician Myrto Schaefer, with the relief organization Doctors Without Borders, says the group has been giving antibiotics to malnourished children anyway. But this is the first study to provide solid evidence for the practice.

“However, what we don’t know is whether the results of this study can be easily transferred to the areas where the majority of children with severe malnutrition live," said Schaefer.

Schaefer says severe malnutrition is most serious in the Sahel region of Africa. But malnourished kids there do not show the same symptoms as those in Malawi, where this study was done. That suggests the underlying causes are different, and go beyond just the lack of food.

In fact, Trehan is co-author on an accompanying study that suggests the types of microbes living in the Malawian children’s gastro-intestinal tracts may be contributing to their malnutrition.

“You could give them the right diet, but if the right bugs aren’t there to help liberate your zinc, or your vitamin A or your proteins, then you’re not going to really absorb them and use them for growth. And you’re going to get malnourished," he said.

Trehan acknowledges it's not really clear why the antibiotics are having the effect they are. He says that’s what he plans to spend the next several years studying.