"What this means is, when you look up at the thousands of stars in the night sky, the nearest sun-like star with an Earth-size planet in its habitable zone is probably only 12 light years away and can be seen with the naked eye," said UC Berkeley graduate student Erik Petigura, who led the analysis of the Kepler data. "That is amazing,"

Petigura, along with his colleagues Geoffrey Marcy from UC Berkeley and Andrew Howard from the University of Hawaii, have had their analysis published online in the journal Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

The researchers point out that just because an exoplanet is Earth-sized or is in an Earth-sized orbit does not automatically mean that it can to support life, even if their orbits are within a star’s habitable zone, where temperatures are not too hot or too cold.

"Some may have thick atmospheres, making it so hot at the surface that DNA-like molecules would not survive," Marcy said. "Others may have rocky surfaces that could harbor liquid water suitable for living organisms. We don't know what range of planet types and their environments are suitable for life."

Last week Marcy, Howard and their colleagues made news when they announced that they found Kepler-78b, an Earth-sized exoplanet with the same density and a core made up of the same mixture of rock and iron as our own planet.

But since it orbits so close to its star, this newly-discovered rocky planet has a blazing surface temperature of about 2,200 degrees Kelvin, which is far too hot to support life as we know it.

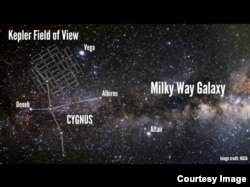

The team focused on 42,000 stars that are like the sun or slightly cooler and smaller. Among those stars, the researchers said they found 603 candidate planets orbiting them. Of these candidate exoplanets, only 10 were Earth-sized, meaning that they were about one to two times the diameter of Earth and orbiting their star at a distance that would provide life supporting temperatures.

To find how many other Earth-sized planets residing in habitable zones they missed in their search, the researchers put planet-finding algorithms devised by Petigura through a number of tests. In these tests, Petigura actually threw in some fake planets into the actual Kepler data to find out which planets his software could detect and which it couldn't.

"What we're doing is taking a census of extrasolar planets, but we can't knock on every door. Only after injecting these fake planets and measuring how many we actually found, could we really pin down the number of real planets that we missed," Petigura said.

Taking several factors into consideration, such these missing planets, and that only a small number of Earth-like exoplanets are situated in such way that they can be seen transiting in front of their host stars from Earth, the team estimated that 22 percent of all sun-like stars in the galaxy have Earth-size planets in their habitable zones.

"Until now, no one knew exactly how common potentially habitable planets were around Sun-like stars in the galaxy," said Marcy.

Although they found all of the possibly habitable planets circling around cooler K stars, or Orange Dwarfs, which are somewhat smaller than our sun, the researchers said that the results of their analysis could also be inferred to G stars like the sun.

The researchers speculated that if the Kepler spacecraft hadn’t been crippled by technical malfunctions this past spring and was able to fully continue its research mission, it would have been able to gather enough data to directly detect some Earth-size planets in the habitable zones of G-type stars.

This new, more thorough analysis of Kepler data made by the researchers shows that "nature makes about as many planets in hospitable orbits as in close-in orbits," said Howard.