At Wakefield High School in Arlington, Virginia, outside Washington, some high school seniors are bent over their laptops, engaged in a digital course called Checkology that helps them figure out what makes news and information real, misleading or just plain false.

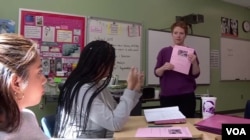

The students are led by their social studies teacher, Patricia Hunt, who said the problem is that many of them don’t know the difference.

She challenges the students to look for signs of a false story by using TV programs, current affairs shows and social media.

“Let’s take a look at some viral rumors,” she said to the group, as she discussed last February’s high school shooting in Parkland, Florida, where 14 students and three teachers were killed. “How many of the rumors that circulated after the shooting were real or false?”

One student mentioned a fake image of Parkland student Emma Gonzales tearing up the U.S. Constitution.

“Students are bombarded with information, and also with so-called news, fake news, viral rumors and misinformation,” Hunt said. “I hope the class will help them to identify quality journalism when they see it, as well as unfair, unbalanced and fake news, and propaganda.”

Not always easy to spot

But sifting through what is real and what is not is difficult, especially because the term “fake news” is frequently used by President Donald Trump, other politicians and journalists, and on social media platforms such as Twitter.

Studies have shown that teens get most of their information from social media, using popular platforms like Instagram and Snapchat. They are more likely to believe information sent to them by their friends.

“I’ve really been struck by how students tend to see all information as created equal,” said Alan Miller, a former journalist and founder of the nonprofit News Literacy Project, which includes Checkology, launched in 2016.

“If they’re younger, they may think that if somebody put it on the internet, they’ve verified it, and it’s all true,” Miller said.

Critical thinking

“By the time they’re in high school,” he added, “they’re more cynical and may feel that it’s all equally driven by bias, by agenda. What’s missing is that critical-thinking skill to know what to do with all of that information and all those images. What we want the students to take away is the ability to assess the credibility of all news and information they encounter.”

Checkology is used by thousands of educators in the United States and in 90 other countries. The Wakefield students indicate it seems to be working.

“Now, I know how to decipher what’s real and what’s fake, and what to look for,” said Amory Gant, who admitted that before taking the class, she believed a lot of false information.

“I learned about fact-checking and ways to find false news by headlines, and seeing if there are publishers,” Sihin Yibrah said.

Kevin Florimon said Checkology has made him more aware of fake news.

“I will be able to go through the news a lot better and rest easier, knowing that I’m not going to be tricked as easily,” he said.