Across the globe today, entire communities are being displaced. More than 50 million people are now refugees. Many may never be able to return to their homes. Among the many challenges they face surviving day to day, is the need to preserve their culture, so its stories and songs are not lost.

Sometimes all it takes to save that heritage is one dedicated individual. For European Jews after World War II, survivors of the Nazi Holocaust, refugees in New York City, one such individual was Ben Stonehill.

A personal cause

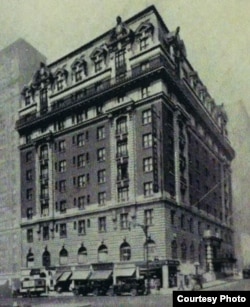

Stonehill, an immigrant himself, was a secular Jew, a carpet-installer by trade. He grew up in a Yiddish-speaking home, was a devoted collector of folklore and wanted to find a way to preserve Yiddish culture. When he learned that Jewish refugees were gathering at the Hotel Marsailles in Manhattan, he borrowed audio equipment, hauling it on weeknights and weekends during the summer of 1948 into the hotel lobby, asking each person to sing whatever song they felt like singing. "He took upon himself to do this recording," explained linguist and Yiddish scholar Miriam Isaacs. "There was an awareness that Jews had an important culture, and that these cultural treasures were in danger of being lost and that these survivors were the last authentic carriers of this eastern European Jewish culture."

Stonehill described the scene, in a speech he made in 1964.

A babble of tongues

"Graduates of Auschwitz, Treblinka, Majdanek and all the others greeted one another unashamedly before my very eyes and into the recorder, which was in constant operation daily from morning till way past midnight. Suckling babes, bearded rabbis, swarthy youths, blond-haired maidens and Hassidic-garbed followers of one or another dynastic rabbi spoke their varied anguished utterances that, in playback, constitute a veritable babble of tongues," Stonehill said.

Masha Leon sang "Tuk Tuk Tuk" into Stonehill's recorder as a teenager. She had emigrated to New York two years earlier, and would come to Hotel Marsailles from her home nearby to meet boys. She still has vivid memories of the scene in the lobby.

"It was full of people – you had older people, sitting on suitcases, toward the back. There was a balcony with refugees coming in and out, that I really paid very little attention to, but the action, the younger people were all in the lobby. It kind of hummed. It was like an orchestra of people kind of melding and working together," Leon said.

Preserving the sounds of the past

The enormous task of scrutinizing the 39 hours of recordings, and categorizing, transcribing and translating the songs fell to Isaacs. She has spent the past three years on this painstaking process.

"My first challenge was, what do you do with 39 hours of untracked sound," she said with a laugh. "That includes everything from babies crying and horns honking, and people chatting, and because it’s only almost entirely just an aural archive, I often don’t know who is doing the singing, know very little about the singers. Occasionally we have their names and where they come from. But very often not," she said.

Isaacs has transcribed 66 of the songs thus far, which are archived and catalogued on the Center for Traditional Music and Dance website, which also includes the original audio.

The work is especially important today, she insists, as more people are driven from their homes every day.

"We all need to understand what it’s like to be a refugee. Not from a statistical point of view, and not because of shocking horrors, but what it’s like to be without a home, what it's like to know that you're never going to go back to your homeland, to not be sure where you’re going to go next,” Isaacs said.

These songs really express the emotional heart of being in that place, trying to cheer yourself up, trying to be hopeful while at the same time, giving voice to loss, and grieving," she added.