Every election has its share of winners and losers, with one political party taking the reins of power. But that's not the case in Oregon where the most recent elections left the state House of Representatives evenly split. That means 30 Democrats and 30 Republicans must now learn to share power.

And what happens when the lawmakers convene on Feb. 1 could serve as a model for the entire country.

Co-speakers

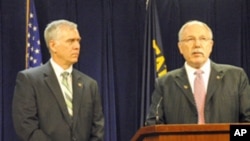

To begin with, the two sides agreed to elect Co-Speakers of the House. That leaves the top Democrat and the top Republican with plenty of logistical details to work out, starting with what to call themselves.

"Republican speaker, Democratic speaker, we've talked co-speaker. It is difficult. There's no script written for it," says Republican Bruce Hanna.

He and his Democratic counterpart, Arnie Roblan, are officially "Co-speakers" but have agreed to simply call themselves "Speaker." The two also divided up premium office space and worked out a plan for who gets to hold the gavel. They'll trade off every other day. And while gavel pounding is mostly symbolic, it's part of the Co-speakers' goal of bi-partisanship.

"We will make it so that at the end of the day, people who look at this session will say 'Wow, they pretty much did that right down the middle,'" says Roblan.

Answers to thornier questions - such as how bills get assigned to committee or make it to the floor for a vote - were negotiated during a month of closed-door meetings. One compromise is that each legislative committee will get co-chairs - one from each party.

Tied chambers

Tied legislative chambers aren't as rare as you might think. In fact they're so common that the non-partisan National Conference of State Legislatures has someone who keeps track of them.

Brenda Erickson says there's been at least one tied state chamber following every general election since 1984. "We always tell the legislators that they should view it as a challenge and not as a dilemma."

According to Erickson, lawmakers have developed several models to deal with a tie. Some, like the Oregon House, try to divide control as evenly as possible. Others give one party the reins for the first half of the session, and then switch at the midpoint. Then there are those who take a more casual approach.

"In Wyoming, way back in 1974, they actually did a coin toss to break the tie," says Erickson.

Collaborative rule

"We have a great opportunity here to do one of two things," says Oregon Republican Sal Esquivel, who sits on four committees and has leadership roles in three of them. "We can either get nothing done, or we can get a lot done. Every vote that comes out of this House will be bipartisan. It can't come out without it."

That bipartisan spirit will be tested as lawmakers deal with a $3.5 billion budget shortfall.

The Oregon House isn't the only tied legislative chamber this year. The Alaska Senate is knotted up 10-to-10. And if Oregon Republicans are disappointed they didn't take one more seat to turn the tables on Democrats, they can console themselves by looking at the Hawaii Senate, where Democrats outnumber Republicans 24 to 1.