“My granduncle — cousin of my grandfather — was a Catholic priest who was put in the labor camp when the communist regime barbarically tried to destroy all the monasteries,” said Miriam Lexmann, one of dozens of legislators from around the world who gathered in Rome last weekend on the sidelines of the G-20 summit.

Their message for the leaders of the world’s richest countries: Take a tougher stance toward the Chinese government, and stand up for those who are threatened by Beijing’s policies, from Xinjiang to Taiwan.

The so-called "counter-meeting” was organized by the Inter-Parliamentary Alliance on China (IPAC), comprising some 200 parliamentarians from countries as diverse as Italy, the Czech Republic, Canada, Belgium, Sweden, Uganda, Japan, India, Australia, Britain, Ireland, France and Switzerland.

For many of the European members who participated, the sense of urgency in standing up to China stems from bitter memories of communist repression within the now defunct Soviet Union.

Lexmann, a member of the European Parliament representing Slovakia, said that during the Soviet period, many of those considered dangerous to the regime in her country were taken away to labor camps.

“Many died in those camps due to the horrible conditions there,” she told VOA in a phone interview from Rome. “My granduncle died in 1952,” two years after he was taken away.

The granduncle’s brother was also a Catholic priest, and he was imprisoned for nine years for having taken part in a movement to let foreigners and countrymen alike know what was going on inside the Slovak region of what was then Czechoslovakia.

“These two granduncles had died long before I was born,” said Lexmann, who was born in 1972. But another member of the family, whom she did know as a child, was active in the underground church in Czechoslovakia.

“He organized in 1988 the Candle Demonstration. People holding candles went to one of the main squares in Bratislava demanding that Czechoslovakia act in accordance with the international human rights treaty the country’s government had signed,” she said.

Such memories, Lexmann said, gave her an understanding of what totalitarian regimes are about, as well as what people did to fight against them. “All this has helped me see why it’s important to defend freedom of man,” she said.

Memories of Soviet rule also helped motivate Dovile Sakaliene to fly to Rome from her home in Lithuania to take part in the IPAC gathering.

“Lithuania has suffered badly under the Soviet communist regime,” she said. “Unfortunately, what the Chinese government is doing, on many levels, is worse.”

Yes, neighbors were asked to spy on each other in the Soviet Union, she said. “But nobody came to your house, sat on your sofa and stayed in your house 24-7 to watch how you feel after one of your family members was taken to the camp.”

That, said the Lithuanian lawmaker, is what happens in China’s northwestern Xinjiang region when members of the Uyghur Muslim population are incarcerated.

“We must raise the question: Is this really going to stay within the borders of China? Are we all, in 20 or 30 years’ time, going to be living in the neighborhood grid-control system, spying on each other, reporting on each other?

“This is not a rhetorical question,” she continued, pointing out that China now has the technology and manpower “to produce traumatized generation after generation — not just to have their private lives invaded, but their private lives deleted.”

Sakaliene said Beijing seems set on not only using technology to control the population “but constantly developing (new) technology to monitor human beings even more (closely).”

The Chinese government has repeatedly defended its policies in Xinjiang, maintaining that what the West describes as detention camps are in fact training facilities where Uyghurs are provided with new skills.

But for Pavel Fischer, Senate Foreign Affairs Committee chair in the Czech Republic, “What we see happening in China is exactly what happened to us during the Soviet times, as my parents would say.”

Fischer, who spoke to VOA from Prague, also journeyed to Rome to participate in the IPAC bid to raise awareness about what is happening in China and the impact that China’s political system could have on the rest of the world.

“It is our duty to share our experiences” of life under communism, said Fischer, 56, who served for eight years as an aide to Vaclav Havel, the Czech dissident and playwright who became the country’s first democratically elected president.

To Fischer, Lexmann, Sakaliene and the others who gathered in Rome last week, that duty includes showing support for Taiwan.

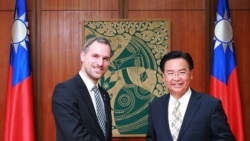

Joseph Wu, minister of foreign affairs on the self-governing island, also spoke at the IPAC event, which was attended by activists from Hong Kong and Xinjiang.

This past week, Wu visited Slovakia and the Czech Republic before making a stop in Brussels, headquarters of the European Union, in a diplomatic coup that Beijing denounced as cuan-fang, roughly translated as “tour of an outlaw.”