JUBA —

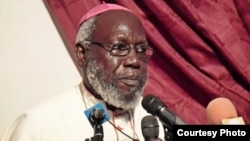

South Sudanese Catholic Bishop Paride Taban worked to shelter and feed thousands of people during decades of conflict that killed some two million people. When a peace deal was signed in 2005, Taban's quest for the deal to last led to the foundation of a "peace village."

Now a shining example in a country still torn apart by proxy fighting, tribalism and cattle-raiding, the United Nations has awarded him a peace prize, the 2013 Sergio Vieira de Mello Prize, in recognition for his efforts in promoting peace in communities within the young nation. Vieira de Mello, a former United Nations human rights chief, died in a bombing in Iraq 10 years ago.

Taban’s path to the priesthood was not what he had imagined. Ordained in 1964, after missionaries were expelled from Southern Sudan and the first civil war started, he was one of a handful of priests who regularly came under fire.

“I remained throughout with the war, under bombs, under persecution and many intellectuals and priests had to leave the country," he said. "There were like three priests in Juba, because the rest had to flee for their life. But, we were like under house arrest. And, one of our priests was in prison, accused of having supported the rebels with the weapons, when it was the army that put weapons in his car.”

Despite witnessing many people shot, bombed and starved to death, Taban says he could not bear to leave his flocks in their greatest time of need.

As Taban became a bishop in 1983 in Torit, state capital of Eastern Equatoria and one of the harshest battlegrounds between the rebel movement and Sudanese government forces, another war started that would last for 22 years.

Taban survived a rebel attack that took out around 50 trucks donated to the church to deliver food to famine-plagued areas. More than 100 people were wounded in the attack, and Taban decided he survived because God had “greater plans” for him.

Peace village concept

The inspiration for the peace village came from Taban’s childhood in a British-owned sawmill that brought people, including his parents, from all over Sudan, and his two wartime visits to Israel.

“I found a small cooperative village in Israel … and there, Israelis, Palestinian Jews, Christians, Muslims live in that cooperative as one community. So, I say why not found one of these communities in South Sudan as an inspiration?” he said.

In 2004, Taban picked Kuron as the site of a “peace village” as it was gripped by violent cattle raiding, a practice that he abhors and made him vegetarian, with clinics, schools, and farms now struggling to meet demand in a desolate country lacking basic services.

South Sudan’s government spokesman, Barnaba Marial Benjamin, hopes that after “tremendous pain and suffering”, role models like Taban will encourage more “model villages”.

“Bishop Paride Taban is a man who had done his good religious work, community work, social work, in an environment in the days of the liberation war, and now after peace, I think he deserves it. And so, on behalf of the president and the government, a thousand congratulations,” said Benjamin.

The United Nations peacekeeping mission also recognizes this “home grown” example of peace and reconciliation in South Sudan.

A South Sudanese Desmond Tutu

Former priest Dan Eiffe, who lost his heart to South Sudan about 25 years ago and also dedicated himself to the struggle, says that Taban is South Sudan’s answer to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who took on apartheid in South Africa and reconciliation in its aftermath.

“He’s the person here with the greatest integrity and an example of peace, so we wish him a long life, as we need him very much for this role that Tutu played in South Africa - I think the truth and reconciliation. And, [he’s] greatly loved, greatly respected and very much deserving. I don’t know how they got to give him this award, but it’s not a boost to Bishop Paride, it’s a boost to South Sudan and some of the great people we have here," said Eiffe.

Even now, the spritely 76-year-old calls himself “a refugee from heaven,” who will never leave his country and will only retire when he goes to his grave.

Now a shining example in a country still torn apart by proxy fighting, tribalism and cattle-raiding, the United Nations has awarded him a peace prize, the 2013 Sergio Vieira de Mello Prize, in recognition for his efforts in promoting peace in communities within the young nation. Vieira de Mello, a former United Nations human rights chief, died in a bombing in Iraq 10 years ago.

Taban’s path to the priesthood was not what he had imagined. Ordained in 1964, after missionaries were expelled from Southern Sudan and the first civil war started, he was one of a handful of priests who regularly came under fire.

“I remained throughout with the war, under bombs, under persecution and many intellectuals and priests had to leave the country," he said. "There were like three priests in Juba, because the rest had to flee for their life. But, we were like under house arrest. And, one of our priests was in prison, accused of having supported the rebels with the weapons, when it was the army that put weapons in his car.”

Despite witnessing many people shot, bombed and starved to death, Taban says he could not bear to leave his flocks in their greatest time of need.

As Taban became a bishop in 1983 in Torit, state capital of Eastern Equatoria and one of the harshest battlegrounds between the rebel movement and Sudanese government forces, another war started that would last for 22 years.

Taban survived a rebel attack that took out around 50 trucks donated to the church to deliver food to famine-plagued areas. More than 100 people were wounded in the attack, and Taban decided he survived because God had “greater plans” for him.

Peace village concept

The inspiration for the peace village came from Taban’s childhood in a British-owned sawmill that brought people, including his parents, from all over Sudan, and his two wartime visits to Israel.

“I found a small cooperative village in Israel … and there, Israelis, Palestinian Jews, Christians, Muslims live in that cooperative as one community. So, I say why not found one of these communities in South Sudan as an inspiration?” he said.

In 2004, Taban picked Kuron as the site of a “peace village” as it was gripped by violent cattle raiding, a practice that he abhors and made him vegetarian, with clinics, schools, and farms now struggling to meet demand in a desolate country lacking basic services.

South Sudan’s government spokesman, Barnaba Marial Benjamin, hopes that after “tremendous pain and suffering”, role models like Taban will encourage more “model villages”.

“Bishop Paride Taban is a man who had done his good religious work, community work, social work, in an environment in the days of the liberation war, and now after peace, I think he deserves it. And so, on behalf of the president and the government, a thousand congratulations,” said Benjamin.

The United Nations peacekeeping mission also recognizes this “home grown” example of peace and reconciliation in South Sudan.

A South Sudanese Desmond Tutu

Former priest Dan Eiffe, who lost his heart to South Sudan about 25 years ago and also dedicated himself to the struggle, says that Taban is South Sudan’s answer to Archbishop Desmond Tutu, who took on apartheid in South Africa and reconciliation in its aftermath.

“He’s the person here with the greatest integrity and an example of peace, so we wish him a long life, as we need him very much for this role that Tutu played in South Africa - I think the truth and reconciliation. And, [he’s] greatly loved, greatly respected and very much deserving. I don’t know how they got to give him this award, but it’s not a boost to Bishop Paride, it’s a boost to South Sudan and some of the great people we have here," said Eiffe.

Even now, the spritely 76-year-old calls himself “a refugee from heaven,” who will never leave his country and will only retire when he goes to his grave.