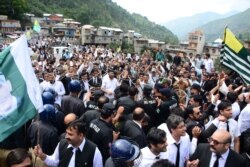

Villagers in Chakothi in Pakistan-controlled Kashmir are frustrated with living in constant fear of fighting along the heavily militarized frontier in the disputed Himalayan region.

Their situation has been exacerbated since India’s government, led by the Hindu-nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party, imposed a security lockdown and communications blackout just over the Line of Control from Chakothi in Indian-controlled Kashmir, which is majority Muslim.

The move followed the Indian government’s Aug. 5 decision to downgrade the region’s autonomy, raising tensions with Pakistan and touching off anger in the Indian-controlled portion of Kashmir.

“India has been killing our brothers and sisters in Indian-occupied Kashmir and the world is silent,” 65-year-old Mohammad Nazir Minhas told reporters Thursday. “It compels us to say that freedom will come only through war. We are ready.”

Journalists were escorted to the village in Pakistan-held Kashmir by the military to show them the plight of villagers living along the frontier. From where Minhas stood, an Indian post could be seen without using binoculars.

Kashmir is split between Pakistan and India and claimed by both in its entirety. Pakistan and India have fought two of their three wars over the disputed region since gaining independence from British rule in 1947.

India on Thursday said it has information that Pakistan is trying to infiltrate “terrorists” into the country to carry out attacks amid rising tensions between the two countries.

Army spokesman Maj. Gen. Ghafoor rejected the Indian claims, saying Pakistan was a responsible state and “we would be insane to allow infiltration” across the Line of Control.

Minhas, who said he lost his daughter in 1971 when she was shot in the chest by a soldier firing from the Indian side, is among local Kashmir residents who say they often spend sleepless nights because of nearby skirmishes between Pakistani and Indian forces.

The nuclear-armed rivals were close to going to war again in February, when a suicide bombing in Indian-administered Kashmir killed 40 paramilitary soldiers. India responded by bombing an alleged terrorist training camp in Pakistan. Pakistan then claimed it shot down two Indian air force planes and captured an Indian pilot who was later released amid signs of easing tensions.

The restrictions on Indian Kashmir have been easing slowly, with some businesses reopening, some landline phone service restored and some grade schools holding classes again, though student and teacher attendance has been sparse.

But tensions between India and Pakistan are high.

“Even last night, there was an intense exchange of fire here,” said Mohammad Salman, 75, a Chakothi resident as he stood in the middle of a deserted market. The market stands about 200 meters (220 yards) from the region’s “Friendship Bridge,” which was opened for a much-awaited bus service in 2005.

Pakistan suspended the bus service and trade with India in response to the Aug. 5 changes to Kashmir’s status by New Delhi. Pakistan has also expelled the Indian ambassador and closed train service to and from India.

Pakistan has indicated it may soon also close its airspace for Indian overflights, forcing them to take longer routes.

Residents of Pakistani Kashmir hail these measures, but they complain the government never constructed community bunkers to protect them from gunfire from the Indian side.

“When our children go out to play, we don’t know whether they will come back alive as India opens fire ruthlessly,” said Mohammad Sajid, 45, as he stood at a nearby mosque.

Authorities say mortar fired across the Line of Control divides Indian and Pakistani Kashmir struck a home in the village of Kail a day before, killing three civilians.

Pakistan’s army says it only returns fire when there is a cease-fire violation by India.

“Our response is always measured and we only target those Indian posts from where fire hits our civilian population,” Ghafoor, the army spokesman, told reporters. He said their troops cannot “ruthlessly return fire like the Indians do” because it could cause civilian casualties on the other side of Kashmir where divided families live.

India accuses Pakistan of training and arming insurgent groups that have been fighting since 1989 for Kashmir’s independence from India or its merger with Pakistan, a charge Islamabad denies. Pakistan says it only provides moral and diplomatic support to these groups.

Most Kashmiris support the rebels’ demand that the territory be united either under Pakistani rule or as an independent country, while also participating in civilian street protests against Indian control.

Villagers at Chakothi say they are waiting for the time when they will “ruin the Line of Control” to hoist Pakistan’s flag in Srinagar, the main city in Indian-administered Kashmir.