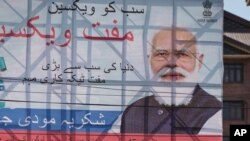

Indian Prime Minister Narenda Modi Thursday offered the possibility of elections in Indian Kashmir, nearly two years after scrapping the region’s semi-autonomous status.

The actual prospect of elections came after a meeting between Modi and pro-India Kashmiri political leaders. Modi said his government was committed to local elections there.

The meeting was the first outreach by New Delhi to Indian Kashmir since the restive Himalayan region was split into two federal territories. The controversial move had been deeply unpopular and deepened alienation in India’s only majority Muslim region, which has been under federal rule for about three years.

Modi said in a tweet after the meeting that, “Our priority is to strengthen grassroots democracy in J&K,” referring to Jammu and Kashmir, one of the two regions.

“Delimitation,” he said, referring to redrawing parliamentary and assembly constituencies so the number of voters in each constituency are roughly the same, must “happen at a quick pace so that polls can happen and J&K gets an elected Government that gives strength to J&K’s development trajectory.”

Delimitation would be a first step toward eventually holding local polls.

Calling the meeting “an important step in the ongoing efforts towards a developed and progressive J&K,” Modi tweeted that he had told the leaders of Jammu and Kashmir “that it is the people, specially the youth who have to provide political leadership to J&K, and ensure their aspirations are duly fulfilled.”

Among the 14 Kashmiri politicians present at Thursday’s meeting were leaders from local parties who have ruled the territory for decades. Many of them had spent months in detention after the abrupt move to scrap the territory’s special status.

Their demands included reversing changes that were made to the territory’s status, conducting elections to restore democracy and releasing all political detainees, according to Congress Party leader, Ghulam Nabi Azad who was present at the meeting.

Thousands of teachers, activists and students were among those arrested in August 2019 and a communication blackout and internet shutdown was imposed for months. The crackdown was meant to tighten New Delhi's grip and prevent a backlash against the move in a region where anti-India slogans were frequently heard at street protests.

“We told the prime minister that we don’t stand with what was done on 5 August 2019,” Omar Abdullah, a former chief minister of the state who attended the meeting, told local television channels NDTV. “But we will fight this in courts.”

The government said scrapping Kashmir’s autonomy was necessary to spur development in the region and end a three-decade armed rebellion by Muslim separatist groups that has killed thousands.

But there has been mounting criticism that New Delhi’s dramatic move has not brought any real political change in the region. On the other hand, there is growing resentment at new laws often drafted by government officials who now administer the region, which is under direct federal rule.

In Kashmir, political analysts welcomed the outreach by New Delhi to local politicians but cautioned that “we will have to wait and watch” and pointed out that the “trust deficit” between ordinary Kashmiris had deepened since the revocation of its special status.

“The start of a process of dialogue is a good first step because it marks a change from the negative and intolerant rhetoric that was heard from New Delhi since Kashmir’s status was changed,” according to Noor Ahmad Baba, former political science professor at Kashmir University in Srinagar. “It is always helpful to change the atmosphere but the process must move forward and not stop there.”

However, he said there is a lot of skepticism among ordinary people who fear that the identity of Kashmiris is under threat from a slew of new laws that remove decadeslong protections for the local population on land ownership and jobs.

Indian Kashmir has been wracked with a violent conflict led by Islamic separatist groups since 1989. India controls roughly two-thirds of Kashmir and Pakistan the rest. Both claim the entire region.