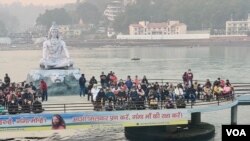

More than a half century ago, the northern town of Rishikesh, nestled in the Himalayan foothills along the Ganges river, emerged on the global tourist map after the Beatles pop group spent some time in a spiritual retreat learning meditation and writing some 40 songs.

Foreign tourists began heading here to learn meditation and yoga. Domestic visitors were drawn by its scenic location and young people came for adventure sports – until the pandemic shut down hotels, hostels and yoga retreats that line the town.

Now as the fear of the novel coronavirus diminishes due to a dramatic dip in India’s cases of COVID-19, cars ferrying visitors from nearby towns are back on the roads and brightly-colored boats with excited rafters course down the river again, bringing hopes of a slow revival to its battered tourist industry.

The foreigners are missing as the pandemic shuts off international tourist travel. But Indians weary from months of work-from-home schedules are making up the shortfall as the country’s huge middle class begins heading to towns like Rishikesh from nearby cities.

“It was very necessary to get out of the monotony,” says Gloria Saldanha who visited Rishikesh with her husband Rahul Jain recently. They drove down from the business hub of Gurugram, where they have been working from home since last March. “We don’t know how long the pandemic is going to last, so till when can you stay shut in the home? One has to start somewhere, and this is our initial step,” she said.

Akash Mital and Nidhi Singla from Delhi visited the town for a pre-wedding shoot as the pandemic failed to dent their enthusiasm for the momentous occasion. “There are so many scenic locations we can use,” said Mital as he enacts a Bollywood number along hilly slopes with his fiancé.

In the past two decades, destinations in Europe and East Asia were the favored vacation haunts of middle-class Indians as decades of high economic growth put surplus income in their pockets – more than 26 million Indian tourists traveled abroad in 2019, spending an estimated $25 billion.

Now they are coming to the rescue of tourist towns like Rishikesh as some opt to travel within the country. Hotel managers in the town say domestic travelers are filling up rooms previously occupied by foreign visitors in scenic spots like Rishikesh.

It is a trend that the country must capitalize on, said Gurbaxish Kohli, vice president of Federation of Hotel and Restaurant Associations of India. “We need to see how to turn these 26 million into domestic tourists, because there are a lot of people who will not be comfortable going overseas, even though some places like Maldives have opened up,” he said. “Even if they spend half or one quarter of the money they did overseas in India, it will help to make up for the 11 million foreign visitors.”

He points out that the travel and tourism industry, which sustains an estimated 40 million livelihoods from cab drivers to hotel employees, is among the sectors hardest hit by the pandemic.

For small villages which dot the hillsides around Rishikesh, the return of visitors is critical – most of the locals work in hotels and other tourism-related businesses but lost their jobs last year as the pandemic ravaged India.

Deva, a cleaning woman at a hotel in Rishikesh, managed to retain her job but her husband, who worked as a cook in another hotel in a nearby city, was not so lucky and was laid off as India went into a shutdown last March.

“He is still at home,” Deva said as she swept and mopped. Selling milk from a buffalo provides some additional income. “It is hard, but we manage. Now my son has gone with his uncle to help out in a company that organizes river rafting,” she said.

Rishikesh is not the only town to benefit as Indians pick up the confidence to travel.

“Weekend destinations near Mumbai have gone through the roof, you cannot get a room,” said Kohli. “The idea is if you cannot go anywhere, let us at least go where we can.”

Thousands of tourists have flocked to Goa, a popular beach destination in western India. In the north, Kashmir shunned by tourists even before the pandemic due to curbs imposed after the government changed the territory’s status in August 2019, witnessed a dramatic change this winter as visitors packed hotels in some of its most scenic spots.

This is making businesses optimistic. “A lot of young people are now coming, especially for trekking,” said Yogendra Rawat, the owner of a company that organizes bungee jumping in Rishikesh.

Kohli warns however that returning to pre-pandemic days is still a long haul. “It’s only going to happen after people get vaccinated. There is still a lot of fear,” he points out.

That is evident. India has reported some cases of the more contagious British and South African strains of coronavirus. The number of new infections has been rising in recent days in some places like Maharashtra state.

The shadow of the pandemic keeps visitors cautious. Saldanha and Jain did not step out of the hotel during their stay, forsaking the mandatory tourist trips to a small Beatles Museum and to the banks of the Ganges where a picturesque, traditional Hindu prayer service held every evening draws many visitors. And the meditation and yoga retreats in Rishikesh may have a long wait for overseas clients as international tourist travel is unlikely to revive anytime soon.